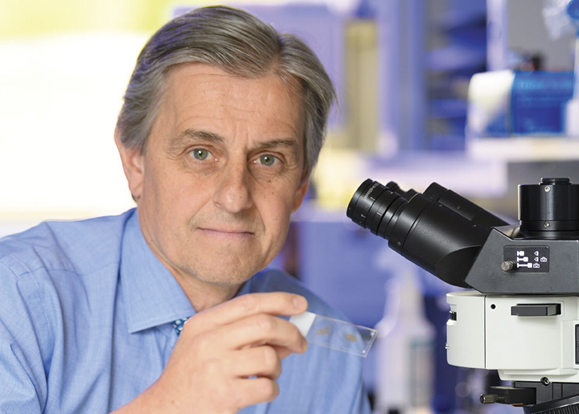

Dr. Kevin J. Tracey, president & CEO of the Feinstein Institutes, is a trailblazer in the neuroscience of immunity, bioelectronic medicine, and unlocking the secrets of the brain.

For those of us fortunate enough to walk and run with ease, it’s hard to imagine living with chronic joint pain and swelling that makes every step difficult, and normal activities like dashing for a bus or taking an aerobics class impossible. Add to that severe abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, and malnutrition, and you have a person with a severely diminished quality of life. Now, imagine that after years of excruciating agony, you take part in a clinical trial and all those symptoms go away.

That is what happened to a patient named Kelly who suffered from Crohn’s disease and inflammatory arthritis for 15 years before receiving a vagus nerve implant. After the operation, Kelly promptly went into remission, no longer needing drugs or her walking cane.

Calling Kelly’s remarkable recovery a miracle would be selling short the decades of research that led to this breakthrough, but one can’t deny the biblical undertones.

“It was absolutely amazing,” says Dr. Kevin J. Tracey, the CEO of the Feinstein Institutes in Manhasset, New York, where we meet on a Tuesday morning in late May. It was Dr. Tracey and his team of scientists at the institute who invented the science behind the electronic device that Kelly received.

Implanted onto the vagus nerve (located on your neck behind where you feel your pulse), this revolutionary device can send signals that block inflammation, the central phenomenon in virtually all diseases.

“We have long known that the nervous system communicates with the body. We can now learn the language by which it communicates, which enables us to fine-tune how we help the body heal itself,” Dr. Tracey says of the groundbreaking work the institute is doing.

On a table in his office, there is a blue glass pyramid about six inches wide, with a canister floating in the center containing the molecule that Dr. Tracey and his research team identified as the neural mechanism for controlling the immunological responses to infection and injury. He said the structure is called a “tombstone” – ironic because of the molecule’s lifesaving properties.

Then there’s Kelly’s old cane that Dr. Tracey keeps in his office, which says much about his personal approach to medicine. As a brilliant neurosurgeon, Dr. Tracey’s focus was one-on-one. Today, he is helping millions more patients by conducting cutting-edge research as opposed to one surgery at a time, but he still appreciates getting to see the individual impact. He sees that in Kelly. She was hired by the institute following her recovery. Now in charge of patient outreach, she works down the hall from Dr. Tracey’s office and is a daily reminder of what has been accomplished, and what he and his team are working towards.

Dr. Tracey’s quest for knowledge of the inner workings of the body began in childhood. His mother passed away suddenly from a brain tumor when he was only five. His not being able to comprehend why doctors couldn’t just remove the tumor without destroying her brain is the key to his becoming a neurosurgeon. Another tragedy, a young baby in his care dying of sepsis, turned his attention to immunology and led him to become a leader in the study of the molecular basis of inflammation and the co-founder of the Global Sepsis Alliance. He is also the author of Fatal Sequence: The Killer Within, and more than 320 scientific papers.

For all the groundbreaking work that Dr. Tracey has done throughout his varied career, there is still more to come.

“The most exciting advances in science come when you cross fields,” he tells me. He has now merged together molecular medicine, bioengineering, and neuroscience into an entirely new hybrid field – bioelectronic medicine, which consists, as in Kelly’s case, of inserting small implants under the skin that control the electrical signals sent out by the nervous system to dictate cell behavior, which limits the need for expensive medications.

Eventually, Dr. Tracey hopes these devices can be used to treat a variety of diseases, including cancer and possibly paralysis.

Medicine aside, Dr. Tracey’s office also holds many mementos of his life outside the institute. Photographs of his family, his wife Tricia, and their four daughters, Maureen, Mary, Katherine, and Margaret, abound. On his desk sits a bobblehead of Abe Lincoln given to him by his daughter Margaret because he re-reads the Gettysburg Address before writing one of his talks. It was Lincoln who famously said, “Determine that the thing can and shall be done, and then we shall find the way.”

Now there’s a quote that perfectly frames Dr. Tracey’s dedication to his work.

Did you always want to be a doctor?

I always wanted to be a scientist. My grandfather was a professor of pediatrics at Yale Medical School, living a life that combines science and medicine. After my mother died I remember asking him to explain it to me. He told me that if the surgeons had done anything more, they would have had to damage my mother’s brain in order to get the tumor out. She wouldn’t have been who she was.

I remember saying to him, “Someone should do something about that. Someone should figure out a better way.” He said, “Well, maybe you will.” For as long as I can remember, I have wanted to be someone who would find a better way of doing medicine to help people.

After medical school, I trained in neurosurgery at New York Hospital Cornell for nine years and then practiced as a neurosurgeon for ten years here at Northwell. But after 24 years, I retired as a neurosurgeon and I put all of my attention on research. I had loved doing neurosurgery, but as the research enterprise grew and the discoveries that we made became so tangible, I became convinced that I could help more people by focusing on projects that could affect millions as opposed to one person at a time.

Do I miss the patients? Yes. Do I second-guess it? Never. Not once.

Does your background in neurology help your research work?

It didn’t in the beginning. Arguably, you never know what’s helping what. One of my favorite quotes is from Louis Pasteur: “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Another from Isaac Newton: “If I’ve seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants. “Somehow in science, you accumulate knowledge, and the most exciting advances in science come when you cross fields.

It wasn’t a plan that I would study neurosurgery and then study immunology and combine them. Most people, looking back over their lives, can connect the dots in a way that tells a story. But I’ve never met anyone who actually had a complete plan at day zero. It’s interesting to put everything in perspective from your experience – what happened to you and what you wanted to happen – but I could not have predicted what would happen by combining these worlds.

About 20 years ago, my experience in neuroscience/neurosurgery and immunology/inflammation did come together in a really big way that led to a new field called bioelectronic medicine.

We discovered that it is possible to build devices to control the signals in the body’s nerves – hack into the nerves if you will. Once we’ve done that, we can use the signals in the nerves to control targets in the body’s cells that are the targets of drugs. Simply put, we can build devices to replace drugs.

How did the discovery come about?

It started very simply. We were working on mice and rats that had brain damage from a stroke. We put molecules into the brain that block inflammation. We had worked on it for years, and we thought we knew everything about that molecule as an anti-inflammatory drug.

But one day when we put that molecule into the brains of the animals, it blocked the inflammation in the brain as we thought, but what we didn’t expect – and couldn’t explain for months – was that the drug in the brain also turned off inflammation throughout the body. This made no sense at all. How could a teeny bit of a molecule in a brain turn off the immune system throughout your body?

It was turning it off in a beneficial way, blocking inflammation. We knew if you could block inflammation, you could treat diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, but we couldn’t understand the connection between the brain and inflammation. Over many years, we discovered that the connection is a nerve called the “vagus nerve,” that leaves your brain and goes to your spleen and other organs. The vagus nerve acts like a brake, like the brakes in your car, stopping inflammation from accelerating. So, we said, if the signals are in the vagus nerve, we should be able to build electronic devices to turn on the brakes in the vagus nerve. That’s what we did, and it worked.

SetPoint Medical Inc., a company I co-founded to develop this idea for clinical studies, has now implanted the devices in patients whose drugs for Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis had failed. There are people in Europe and the USA walking around today with vagus nerve implants in their necks, who don’t have to take drugs anymore. It’s a whole new approach to developing a therapy for patients.

Is it true that before this, scientists thought the two systems didn’t interact?

Not in a specific way. We knew that when inflammation starts, the body has mechanisms to turn it off, but those mechanisms were all blood-borne molecules, like hormones. For example, steroids from your adrenal gland will turn off inflammation.

And it was known for decades that organs of the immune system, like the spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow, contain nerves.

What was never appreciated before my colleagues and I made some discoveries in this space was that the nerves are actually working like a reflex to control the inflammatory cells. Think of a very simple reflex, like touching a hot stove. It burns you. As soon as the pain starts, your nerves pull back your hand before you even realize it; you don’t think about pulling your hand back. That’s a reflex.

In a reflex, there’s a signal, the pain or the heat, which goes up to the nervous system, and then there’s a returning signal, which goes back to the muscles of your hand and arm and pulls your finger away. We postulated that perhaps the immune system is also controlled that way, so we mapped it out as a thought experiment. How would it work? The way it would work is first you have inflammation caused by molecules such as TNF (tumor necrosis factor). This inflammatory molecule activates a signal that goes up to the brain as the input of a reflex. Then the signals coming back down from the brain travel to the vagus nerve to turn off any further inflammation. Like touching the hot plate and pulling your hand away, TNF touches the nerve and the nerve turns off inflammation. That’s the inflammatory reflex.

What is the key to being a good researcher?

The key to my research is trying to understand how things work, taking them apart so you can put them back together. Doing that led to understanding the signals the nerves are using to turn off the TNF, then building devices to replicate those signals to help people.

What do you like to do when you’re not researching?

Spending as much time as I can with my wife, Tricia, and our four daughters is the biggest priority in my life. Discoveries come and go, but your family is with you forever.

I’ve been very fortunate to see some of my work help individual patients, launch companies, and create jobs, and that’s all very gratifying, but nothing beats the satisfaction of being with my girls and Tricia. As busy as work can be, I make time on nights and weekends to spend with them.

When I have time for hobbies, I like to fish, mostly during summer vacation. I also love woodworking year-round. I love to build things. Being able to take a piece of wood and turn it into something that did not exist before, building something from nothing, is just really a great hobby for me. I like to build things that get used: cabinets and tables. And I built a playhouse for my kids that’s now heated and air-conditioned. I have a workshop in my barn in the backyard outfitted with table saws and miter saws and jointers. It’s better than a home office. It’s really fun.

It seems like the same technique of taking things apart and putting them back together.

There is a theme here, yes! There’s definitely a theme of building and creating. The other thing I like to do is write. I wrote one book and I hope to work on another one. I enjoy reading, too. Reading and writing are incredibly important to a life of science. Work not published is work not done.

There have been many, many scientific discoveries that were really important but never heard of because they weren’t integrated into a story that people could understand. I learned from 24 years of talking to patients that when you take the time to explain something, it’s better for everybody. It’s better for the patient, and it’s also better for other scientists to understand what you think your findings mean and how it integrates into the world of science.

In business and in leadership it’s incredibly important to schedule a time to think clearly about the message you’re trying to communicate. There’s a sign hanging on the wall here of Henry Ford’s quotation: “Thinking is the hardest work there is, which is the probable reason why so few engage in it.” It takes a lot of work to say the right thing, and the best way to say the right thing is to write it down first. But in order to write it down, you have to really think it out.

My hobbies do overlap with what I do at work. But I’ll say it to you backward: I’m one of the very fortunate people who has gotten to spend much of my working life as if it were a hobby. I go to the laboratory with my colleagues, who are brilliant, and I get to hear their ideas and we get to build things together. We focus on ideas that other people haven’t thought of or haven’t tried. We’re creating; we’re sculpting ideas into tools that can help people.

There’s a continuum there between reading and writing and communicating and building. I feel very fortunate to be able to spend so much of my time in the lab, quote-unquote “at work,” feeling like I’m doing a hobby.

It’s like that quote: “If you find what you love to do you’ll never have to work a day in your life.”

I’m living that quote. Is every day perfect? No. Are there stresses and strains of raising money for a laboratory or a research institute? Of course, there are. Does every experiment work? No. Does every paper that you write get accepted the first time, or does every grant get funded? No, no, no. There are definitely good days and bad days, but I’m very lucky to be doing what I love. A lot of people don’t get to do what they love.

Even more so because what I love to do is make things that will hopefully help a lot of people. The satisfaction I get from meeting a patient who has benefited from something that I had a role in inventing can’t be replaced by anything. It’s what makes it all worthwhile.

Is your household pretty Irish?

Yes. I am married to Patricia McArdle, who is second-generation Irish with ancestors from Donegal. Her brother Brian recently visited the original homestead there and reconnected with some distant relatives. My great-grandparents emigrated from Westmeath in the early 1900s. A few years ago my brother Timothy (named after my great-grandfather) visited the ancestral cottage and found it still standing deep in the pastures of an active farm. So Tricia and I do indeed celebrate our Irish heritage with our daughters.

Have any of your daughters shown interest in going into medicine?

Yes. Maureen majored in neuroscience and behavior and is now a nurse specializing in geriatrics. She has tremendous compassion for the elderly, which is a huge need today with the aging population and with Alzheimer’s and neurodegenerative diseases.

Mary Bridget majored in special education and teaches middle school children with learning disabilities. It takes sincere compassion to work with students with ADHD, autism, and other special needs. Today’s learning environment is very complex. There is a strain on the parents and financial pressures on the school districts. And Mary is immersed in the entire process for the sake of the students.

Katherine is a neuroscience and behavior major at the University of Notre Dame – the home of the Fighting Irish, of course. She is going to pursue a career as a physician assistant and has already found her passion in working with patients in intensive care units, respiratory care centers, and as a trainer in the athletic department at Notre Dame.

Margaret is still in high school, and not yet considering a profession. She has many interests and she has the curiosity and persistence to do well in whatever she sets her mind to, whether she follows her sisters into medicine or education, or charts an entirely different course.

Is patience one of your virtues?

If you ask those who know me at work, it is not likely that the first word springing to their mind would be ‘patient.’ I’m impatient for results. Fortunately for my family and I, Tricia is extremely patient and compassionate. That is such a blessing.

I would argue that in science and in medicine, there is a very strange interaction required for success between impatience and patience. People see day-to-day at work that I’m incredibly impatient for the results to be completed when we see the path to completion.

On the other hand, I can be infinitely patient. Some experiments and projects that I summarized for you in a few minutes were the result of 20 years of work. Our work on the inflammatory reflex was the result of hundreds of people working 500,000 hours over 20 years. That requires a certain kind of patience. I have that patience when I see progress occurring, even if I’m not sure what the outcome is going to be. That’s the fun part.

Do you have a certain leadership technique?

My leadership technique is to identify the successes of my colleagues and elevate them. I spend a lot of time identifying the strengths of my colleagues and then restructuring the job around their strengths.

I don’t believe in identifying the job and going and finding the person to fit the job. I don’t think that’s efficient. There are too many things that can go wrong. You can define the job wrong, which happens all the time in big organizations. Or, you can try to retrofit a person who you think is right for the job that you think you defined, but you’re going to be wrong on that at least half the time, maybe more.

On the other hand, if you identify people who share your vision and your passion for success, even if they don’t have the right tools in their toolkit to do what you thought you wanted them to do, you figure out what the tools in their toolkit are, and you have them build that project. Now you have an engaged person who’s doing something that she’s good at, and in the position to shout her success from the rooftops.

You can talk about organizations, business plans, revenue projections, profit, and losses, but at the end of the day, what do people remember? They remember that so-and-so discovered this, and he invented that, and the world’s a better place because she did this and he did that. That’s what matters.

Our mission at the Feinstein Institutes is to produce knowledge to cure disease. The organization isn’t producing knowledge; individual people are. Identify the best people based on what they’re best at, and then celebrate their successes. It’s a fun way to do the right thing, and it’s amazing how far it goes. The rising tide raises all the boats. Others join in and you build a team that way. You build a team of winners.

At a place where there are 5,000 employees, it’s important that the people working here know the successes of their colleagues, and it’s important that the messaging of successful coworkers starts with the coworkers. Then together we take the message outside.

I see that you have an Abraham Lincoln doll on your desk. Are you a big Lincoln fan?

Yes! Margaret, my youngest, gave me that for my birthday last year. It’s an Abraham Lincoln bobblehead doll. I said, “Thank you, Margaret! I love it, but why are you giving it to me?” She said, “Dad, you told me that you write a lot of speeches, and every time you sit down to write a speech, you start by reading the Gettysburg Address.” I said, “Yes, I do.” She said, “Now when you’re reading the Gettysburg Address, you can look at Abraham Lincoln on your desk.” And so I do.

I think that in the history of the world’s best speeches, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address tops the list.

Have you been to Ireland?

Yes, many times. I lived there for a month in 1983 on a combination camping-golfing trip. We would go into a town, find a bed and breakfast, go to the pub, get to know people, and find out about the golf course. We played Ballybunion, Connemara, Lahinch, Portmarnock, and Waterford.

We wanted to get a feeling of living in Ireland. We would alternate bed-and-breakfast nights with camping, either on a beach, in the woods, or on a farm.

We met some of my friend’s relatives in Dingle. I’ll never forget entering the farmhouse with a dirt floor on a Sunday morning. They were the most welcoming, inviting people. With the kids holding on to their mother’s legs, the father brought out a bottle of Irish whiskey. This was clearly only for special occasions. It was unforgettable. I visited recently and the country has advanced tremendously in the past 30 years.

The country is so beautiful and the people are so welcoming and quick to laugh. On more than one occasion I remember being in a pub in some small village somewhere at nine or ten o’clock at night, and half the town would be there singing. John and I would be the only Americans, maybe the only foreigners, listening to these ancient Irish songs sung by people in a traditional way. It brought tears to my eyes. You could just feel the spirit of the country right there.

I’m going back this weekend with my daughter Katherine for a five-day version of that trip – a father-daughter long weekend, and I can’t wait.

What are the values that guide you?

What I value most is my family. What I value most at work is discovering things that will help people. Michael Dowling, the president and CEO of Northwell Health who has been honored by Irish America before, has elevated the priority of Northwell to supporting research because he places a premium on what research does.

“Research,” Michael and I like to say, “is the process of inventing the future,” and inventing the future is the process of making better medicine and better healthcare systems.

For those of us fortunate enough to work on creating value independently from money, it makes all the difference. Luck is very important to what we’ve been able to do. I remember my dad saying, as a man who was very Irish, “what good is it to be Irish if you can’t be lucky?” And I’ve been very lucky.

One of my favorite Irish isms is: what you can imagine, you can achieve. The hard part of that is actually the imagining. Once you imagine it, it actually does come true a lot. To me, that’s very Irish. “Yes, there’s a hard problem, but how can we imagine a solution to it?” Does it happen every time? Of course not. Does it happen more often than it should? Definitely yes!

Thank you, Dr. Tracey. ♦

_______________

Editor’s Note: The implant is not available on the market yet. It is being studied in clinical trials by SetPoint (info@setpointmedical.com). Readers can contact Kelly Owens (who is featured in the article) – she helps with Education and Outreach at Northwell too. Her email is kowens4@northwell.edu.

Good lord, what a long article. Think I’ll take a mid-day nap and then attack it again.

Teasing to me, reduced to life in a wheelchair by arthritis, but I have fun!

Thanks. Later.

Peadar

Oakland

What an interesting doctor. I loved that he has done such great research on the nervous system and that he makes furniture so I sent this to my daughter the doctor and my son the cabinet maker.

Fascinating individual . The procedure to cure Crohns particularly caught my eye as my wife has suffered with illness for nearly 20 years. I wonder if this procedure is still being done.

Loved reading this article on Dr. Tracy, found it so interesting about the work and research that he does. I also love that he knows about his Irish background and is Proud!!

Thank you for interviewing him!!