From rural Donegal to Russia’s Hermitage Museum: the bizarre journey of an Irish landscape by an American artist.

℘℘℘

You would hardly expect to find idyllic scenes of the Donegal Gaeltacht in a Russian state museum, but the celebrated painting “Dan Ward’s Stack” and other gorgeous canvases of rural Donegal grace the walls of two of Russia’s world-renowned art museums. The story becomes even more incredible because the Donegal canvases were gifts to the then-Soviet Union, not from an Irish painter, but from a New York artist who had fallen in love with Donegal.

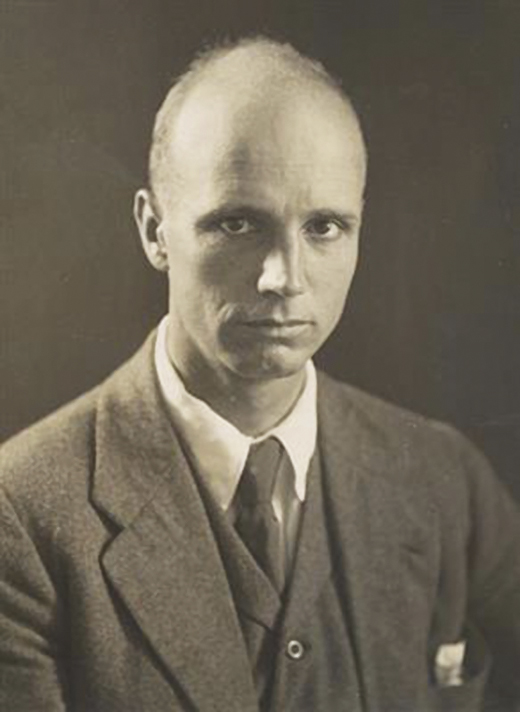

As if the story was not improbable enough, the saga of Rockwell Kent’s Irish paintings becomes even more surreal on account of his background. Kent was an upper-class New Yorker of English background without a drop of Irish blood. Born in Tarrytown, New York, in 1882, Kent attended Columbia University and trained with the finest American art teachers of his day, including Paul Henri, William Merritt Chase, and Wilhelmina and Thomas Furlong. Kent was apprenticed to painter and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer, who stimulated Kent’s interest in painting wild, idyllic landscapes.

In 1905, Kent ventured to remote Monhegan Island, Maine, where he found inspiration in its rugged, primitive beauty for the next five years. His series of Monhegan canvases were met with wide critical acclaim in 1907 in New York. These works earned Kent an enduring reputation as one of the foremost early American modernists, and they still hang in museums across the country, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

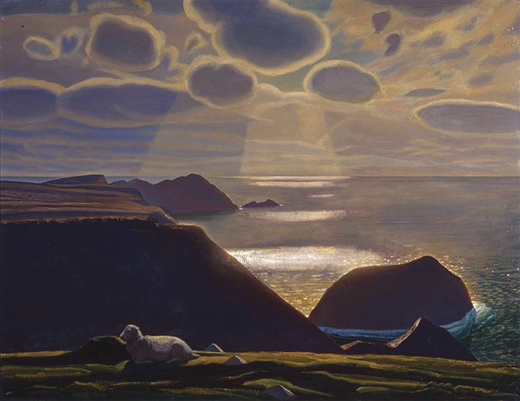

Kent read the work of transcendentalists Thoreau and Emerson and shared their belief that man found peace and spiritual beauty in remote natural settings. He sought out even wilder landscapes than Maine, traveling to Newfoundland and Alaska before ending up in Donegal in 1926.

Seeking solitude and beauty, Kent found them in a remote corner of Donegal, in a valley called Glenlough that was then accessible only by foot.

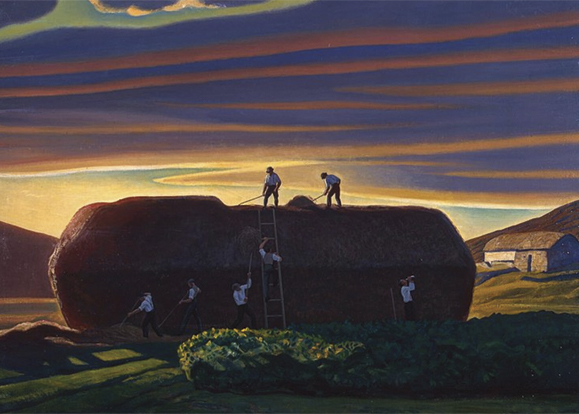

Kent rented a cowshed from local farmer Dan Ward, where the New Yorker set up his studio. Ward and Kent became good friends, and after painting for several weeks, Kent invited Ward and his wife Rose to the cowshed for tea, where they became the first people ever to see his Donegal series. Ward, the story goes, was singularly unimpressed. He stared at the canvasses for ages, and finally, he removed the pipe from his mouth, and blurted out: “Begorra, they’re terrible.”

Undeterred by the criticism, Kent continued his work. One of his finest paintings, depicting Ward building a giant haystack, now hangs on permanent display in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum, while another of his Donegal paintings, “Annie McGinley,” is now in a private collection in New York.

After four months, and 36 Donegal paintings, Kent left for New York, where some of his work was sold into private collections. He kept in touch with the Wards by letter, and was eager to return to Ireland. But fate took a hand. The Depression hit and people had little money for food, let alone artwork. Then came the war, and after that, the Red Scare.

Interrogated by Senator Joseph McCarthy in front of the House Committee on Un-American activities, Kent refused to name names or admit that he was or ever had been a member of the Communist party. He was duly punished: when he tried to leave America, his passport was revoked.

Kent began a long and costly legal battle to regain his passport. In the meantime, his old friend Dan Ward offered to sell him his farm. Finally in 1958, the Supreme Court sided with Kent and, passport in hand, he headed off to Ireland. He arrived at the Belfast docks and took the narrow gauge railway to Killybegs, but he arrived too late. Dan’s place had already been sold.

Pilloried by McCarthy’s supporters in America, Kent was seen as a hero in the Soviet Union. His 1957 Russian retrospective was celebrated and, in gratitude, Ward donated more than 80 of his paintings to the Soviet people.“Dan Ward’s Stack” was among them.

His fame in Russia lived on. Kent became a recipient of the prestigious Lenin Prize before his death from a heart attack in 1971. He was 88, and living in Plattsburgh, New York. His paintings have never had a showing in Ireland, and few people in Donegal knew of their existence, until a recent television program piqued local interest.

Kevin Magee, a correspondent with the BBC, came across a copy of the “Annie McGinley” painting, hanging in a Donegal pub, and set about investigating the American artist who painted the barefoot local girl lying on the cliff edge. Thus began Ar Lorg Annie / In Search of Annie, which was broadcast on BBC2 Northern Ireland in June last year.

Perhaps now, the paintings will finally have an Irish retrospective. ♦

Joseph McCarthy was a senator and was never on the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He was on a comittee of the US Senate. That misrtake must have been made more than a thousand times.