Two words from one Irishman who trumpeted the world’s superpower.

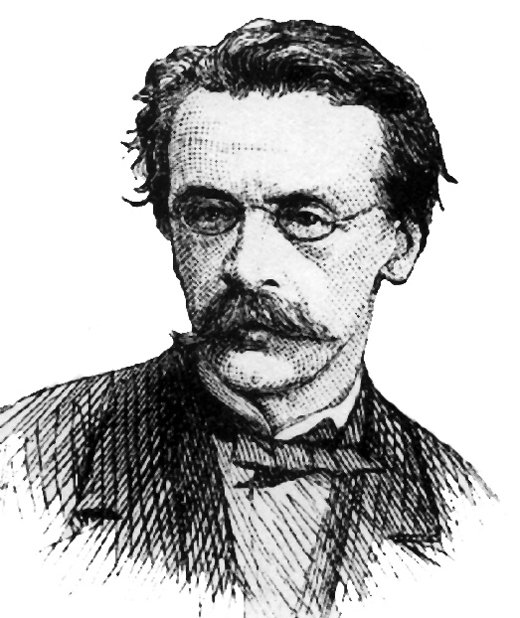

“Manifest destiny…” These words, placed together, command one’s attention. They sound important, almost biblical. But they didn’t come from an Old Testament patriarch or New Testament prophet. Rather, they came from the pithy pen of a 19th-century Irishman named John O’Sullivan.

His ancestors were from County Kerry and included men who abandoned plans for the priesthood in order to become soldiers of fortune. His father was a naturalized American citizen who was serving as U.S. consul to the Barbary States when O’Sullivan was born on a British warship in the Bay of Gibraltar (between Spain and Morocco) in November 1813. According to the National Cyclopedia of American Biography (vol. 12), his family had been living at a nearby military post, but after the outbreak of plague, a British admiral invited them onto his ship.

O’Sullivan received his early education at a military school in Lorize, France, and then at the Westminster School in London, before matriculating at New York’s Columbia College. Upon graduation, he worked as a tutor for a few years. He also practiced law for some time, though it does not appear he was particularly interested or successful in the profession.

The most notable period of his life began in 1837, when he launched a magazine called the Democratic Review. This publication was bankrolled by funds his mother received from the U.S. government as restitution for having been wrongly arrested on suspicion of piracy more than a decade earlier, as relayed by Julius W. Pratt in his article “John L. O’Sullivan and Manifest Destiny,” which appeared in a 1933 edition of New York History.

Though O’Sullivan was foremost a political writer, he also clearly had literary interests. In his leading role at the Democratic Review, he published the short stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne. The two became good friends and O’Sullivan even served as godfather to Hawthorne’s eldest child.

O’Sullivan – who was described by a contemporary as “always full of grand and world-embracing schemes” – had a wild optimism that sometimes irritated people, including Edgar Allan Poe and Henry David Thoreau. However, his magazine became influential enough to attract contributions from some of the nation’s leading writers, whether or not they enjoyed his sanguine style.

The Democratic Review was also the venue that first mentioned “manifest destiny,” which came in the middle of 1845, a year that saw the U.S. embroiled in disputes about whether or not it should annex Oregon and Texas.

This first mention of “manifest destiny” attracted scant notice, likely because it was obscured within a long essay, which typically is not the type of format that attracts a massive readership.

However, the second mention of the phrase appeared in a December 27, 1845 newspaper editorial, a format that often received massive readership. Sure enough, this time the phrase took flight and soon saw frequent use in arguments about the expansion of U.S. territory.

Though not everyone agreed with the concept of “manifest destiny,” O’Sullivan’s words gave voice to a widespread sentiment that the U.S. was a divinely guided nation, which had not only a right, but also a mission, to spread its greatness across the continent.

In O’Sullivan’s view, the U.S. had a “manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.”

In 1846, he sold the Democratic Review for $5,000 (about $165,000 in today’s money). That same year, he married Susan Kearny Rodgers. The couple chose Cuba for their honeymoon, according to Robert Sampson’s book John L. O’Sullivan and His Times. Aside from being a romantic location, Cuba was a place where O’Sullivan was convinced the U.S. should manifest its destiny.

In April 1851, O’Sullivan was arrested in New York and charged with violating U.S. neutrality by preparing an unsanctioned attack on Cuba. He had hoped to liberate the territory from Spanish rule, so as to facilitate its annexation by the U.S. O’Sullivan’s strange case made it to trial, but the jury deadlocked and he was never convicted. Unfazed by this close call, but unwelcome back in Cuba, he became involved in political intrigues in Europe.

Despite his rather freewheeling background, O’Sullivan managed to secure a post as U.S. Minister to Portugal during the administration of President Franklin Pierce (1853-1857). But the end of the Pierce presidency spelled the end of O’Sullivan’s tenure. It also seems to have been the last time he had a consistent occupation.

In the 1860s, O’Sullivan’s political pamphlets – which supported the Confederacy and argued that the U.S. federal government was encroaching too much on states’ rights – made him unwelcome in much of America. Rather than relocate to the South, he self-exiled to Europe, and waited for sentiments to cool down in the U.S. It is unknown exactly how many years he spent abroad, but one of his surviving letters indicates that he was back in the U.S. by August 1879.

According to Pratt, the last three decades of O’Sullivan’s life are veiled in “almost complete obscurity.” What we do know is that, during this period, the U.S. continued to add to its grandeur, and O’Sullivan sunk into poverty.

On March 24, 1895 – almost exactly 50 years after having coined his famous phrase – he died at age 81 in a hotel at 15 East 11th Street in Manhattan. He was buried in the Moravian Cemetery on Staten Island. There was no record of a will. He had basically nothing to leave behind anyway, at least not in the material sense. He did, however, bequeath a phrase that never ceased to echo, or to stir emotions in opposite directions.

Indeed, many have found the “manifest destiny” words troubling, if not downright foul – a glorious-sounding phrase used to justify an already-powerful, nation-grabbing new land, at whatever cost to the native inhabitants. But regardless of one’s historical or political viewpoints, it’s hard to deny the impact of these words.

Many writers have penned thousands of articles and dozens of full-length books; their countless words, eloquent though they may be, almost invariably fade from memory in short order. O’Sullivan put together two words that resonated enough to galvanize a nation as grand as the modern world has seen. ♦

Leave a Reply