Oh! star of Erin, queen of tears,

Black clouds have beset thy birth,

And your people die like morning stars,

That your light may grace the earth.

– “Stars of Freedom,” 1981

By IRA volunteer Bobby Sands, M.P.

H-Block, Long Kesh Prison Camp

Watching Bobby Sands die in 1981, much of the world realized, finally, that the young IRA soldier and hunger striker was a freedom fighter, and the view of the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland forever changed. It was no longer seen as two Irish factions fighting over who had the better Jesus, but rather a struggle for human rights. Sands’ death was another chapter in Ireland’s long history of martyrs and “blood sacrifices.” Two weeks later another IRA hunger striker, one who was not allowed to die, was released from prison – Dolours Price.

Dolours Price grew up with a living blood sacrifice, Auntie Bridie, who in her IRA days dropped gelignite in an explosives dump and lost both her hands and eyes. To Dolours and her sister Marion, Auntie Bridie was a hero, they dutifully lit her many cigarettes and inserted them between her lips. Rebellion was the Price family business: the father was a longtime IRA chief, the mother in the Cumann na mBan, the female wing of the IRA, and at varying times each of the Prices, including old Granny, did a stretch in prison. Dolours recalled, “Our family motto wasn’t ‘For God and Ireland,’ Ireland came before God.”

Northern Ireland was created after Ireland’s War of Independence when, in 1921, the British Government passed an act that employed the Empire’s fallback “solution” – partition. Whether it’s India or Ireland, partition always leads to tribalism and religious conflict. Britain kept the northern six counties with a Protestant majority, known as the “Loyalists”; the other, mostly Catholic, 26 counties became the Irish Republic. In Northern Ireland the Catholics, the “Republicans,” were a minority and subjected to discrimination in housing, jobs, and voting. It was Jim Crow, Irish style.

In the late 1960s, rebellion broke out all over the world as the younger generation found its voice, and the dissent found its way to Northern Ireland. There, the lines of sectarian hate had already been drawn, and the increasing tension was turning violent: The Troubles had arrived. In January 1969, Catholics (and some Protestants), embracing the non-violence of Martin Luther King, Jr., organized the People’s Democracy March, modeled after his Selma march.

Dolours and Marion, now college students, were among the activists marching from Belfast to Derry singing “We Shall Overcome” when they were ambushed by Loyalists and pelted with bricks, pipes, and boards with nails. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) did nothing to stop the assault, instead aligning themselves with vigilante Protestants.

By August of the same year, Great Britain sent its army into Northern Ireland on a “limited operation.” It stayed for the next eight years, the longest continuous deployment in the history of the British military. In 1972, British paratroopers fired on a peace march, killing 13 unarmed civilians, a day forever known as Bloody Sunday. It was a turning point in the conflict. Both sides had become radicalized and now, it was war. The new generation of Republicans formed the Provisional IRA, committed to armed struggle; the Loyalist side spawned more virulent paramilitary groups – the Ulster Defense Association, the Ulster Freedom Fighters, and the most violent, the Ulster Volunteer Force.

Just when it seemed it couldn’t get any worse, it did. The British introduced “internment,” a policy where anyone with a whiff of Republicanism was imprisoned indefinitely, without trial. The army colluded with the RUC and the Ulster paramilitaries, and together they recruited a network of informers, or “touts,” from the Catholic population. Throughout Irish history, informers were reviled, never to be forgiven, and if found out, executed.

Dolours no longer saw anti-violence protest as an option. She left her classes with a rifle hidden under her raincoat, traveled to Maoist headquarters in Milan to give a speech on “British Repression,” and eventually approached the IRA demanding to be a member. She wanted to be a soldier on the front lines; the leadership met and, in 1971, Dolours became the first woman admitted to the IRA. She was 20 years old.

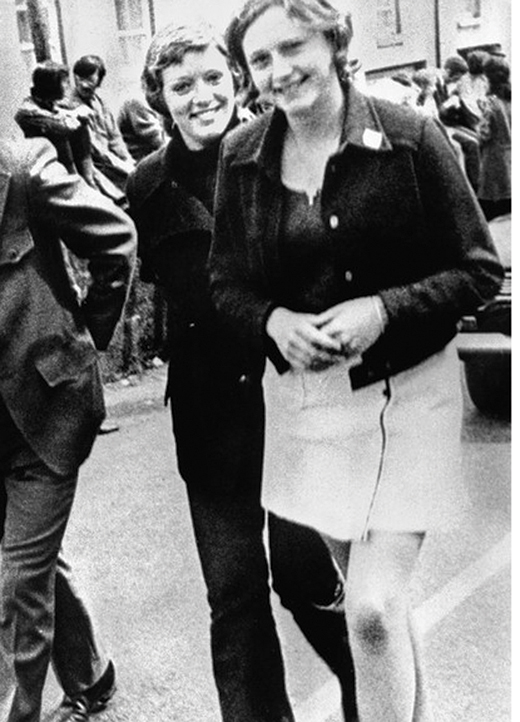

Now named the Crazy Prices (after a Belfast department tore), Dolours and Marion robbed banks dressed as nuns and hijacked cars and postal trucks. Both were glamourous and leggy in the era of miniskirts, and not above flirting with British soldiers – it helped them get past checkpoints to plant bombs. Dolours, in particular, had an ample supply of swagger and, like Che Guevara, became a symbol of radical chic. She volunteered for the Unknowns, a secret society within the secret society that was the IRA. The Unknowns were charged with transporting arms across the border, an operation that expanded to transporting touts across the border to be executed. Those 17 touts later became known as the Disappeared.

In 1973 Dolours spearheaded a plan as audacious as it was doomed: the Unknowns would take the battle from Northern Ireland to England and plant car bombs outside London landmarks, including the Old Bailey. Her team highjacked cars in Belfast and ferried them to London where they were wired with explosives. The bombs were set to go off at 2:50 and the police would get a one-hour notice before they detonated.

The night before the mission, an oddly relaxed Dolours decided to take in some London theater; it was an evening where her past, present, and future intersected. The play, Freedom of the City, was by Brian Friel, a Catholic from the North, and about Bloody Sunday (Friel was a participant). The director was Britain’s “angry young man” and Republican supporter Albert Finney; the star was a young actor, Stephen Rea, a Protestant from the North and Dolours’ fellow activist in the Belfast civil rights movement. Ten years later he became her husband.

The next day police were waiting for Dolours & Co. – they had been set up by an informer. But two bombs did go off, 200 people were injured, and the Belfast Bombers were arrested at the London Airport. The Crazy Prices were now the notorious celebrities, the Sisters of Terror; Vanessa Redgrave offered to pay their bail. During her trial, Dolours mugged, wisecracked and otherwise behaved badly; she and Marion received life sentences in Her Majesty’s prison at Brixton. Once outside the courtroom, Dolours announced she was going on a hunger strike unless she received political prisoner status and transferred to a Northern Ireland prison.

The parents visited Dolours and Marion, now the third generation of their family’s women to be imprisoned for the Republic. Their mother warned the girls, “no tears, not in front of these people.” The somewhat arrogant Albert Price reminded his daughters of his earlier IRA mission to London (with, of all people, Brendan Behan), “I blew them up before you did. The only thing was I didn’t get caught.”

Once inside, the Prices refused food for 33 days. Then authorities, worried about the backlash if the celebrity sisters died, ordered them to be force-fed, a procedure the international community now recognizes as torture. For 167 days, four guards bound their arms and legs to a chair, climbed on top of them, and stuck rubber tubing crammed with slop down their throat. They didn’t break, their resistance worked, and they were transferred to Armagh prison in Northern Ireland. But they had lost hair and teeth and developed anorexia and were now repulsed by food, “to have food was bad, to eat food was failure and defeat.”

The anorexia had put her life in peril, and despite continued opposition from Margaret Thatcher, Dolours, weighing 76 pounds, was released from prison in 1981. This was around the same time Bobby Sands and the other H-Block prisoners were on their hunger strike, a strike that would not have been possible without the Price sisters – because of their ordeal, force-feeding was no longer an option. The British government had stated, “henceforth any prisoner on hunger strike would be allowed to die.”

Out of prison, Dolours, suffering from severe PTSD, effectively ended her fight against the British Empire. She built a new life in Dublin and a new career, writing. She began dating her former friend from the civil rights movement, Stephen Rea. They married in 1983 had two sons and later, art imitating life, Rea was nominated for Academy Award playing a soulful IRA gunman in The Crying Game.

Republican leader Gerry Adams left the fighting too. He moved on to politics, becoming the leader of Sinn Féin, and in 1983 began building a coalition, which included President Bill Clinton, that would lead to a treaty. In 1994, the IRA laid down their arms, a gesture that gave hope to both sides and inspired President Clinton’s speech in Derry. He quoted Seamus Heaney: “History says, don’t hope / On this side of the grave. / But then, once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme.”

In the 40 years from 1968 to 1998, over 3,600 people had been killed, and many others maimed, in the Troubles. On Good Friday 1998, both sides in the long battle reached a peace agreement – hope and history finally rhymed. The government would now consist of Catholics and Protestants, paramilitary groups put down their arms, and the police force integrated.

The treaty was a historic day for Ireland, but an unholy one for Dolours Price. The six counties of Ulster would remain part of the United Kingdom, prompting Dolours to announce that she had notendured torture and “the pangs of hunger strike just for a reformed English rule in Ireland.” The Good Friday Agreement led her to question her wartime activity: were her crimes in the name of Ireland now even justified? Was her cause still righteous? Was she a murderer?

Dolours was further incensed as Adams, with a straight face, denied he was ever in the IRA. She refused to accept the obvious – that his political expediency was the cost of peace. Adams had to talk out of both sides of his mouth since the Brits couldn’t be seen negotiating with a “terrorist” and, just as importantly, he was the only person who could persuade the IRA to put down their arms.

In 2001, the Belfast Project, an oral history of the Troubles sponsored by Boston College, began recording secret interviews with participants on both sides of the conflict. Former combatants conducted the interviews and participants were promised confidentiality: their stories would be sealed until after their death. As the Belfast Project proceeded, attention shifted to the Disappeared who were taken over the border to be executed and buried. Their families demanded the remains, and a commission was set up to locate the bodies. Of the 17 Disappeared, there was only one woman, Jean McConville, a single mother of 10 who was abducted in 1972 and never seen again. Dolours was the driver who drove her over the border to County Monaghan.

For years Dolours had been haunted by her IRA past. By 2003, she was divorced and struggling with depression, PTSD, alcoholism, and an addiction to prescription drugs. She was arrested for forging prescriptions and shoplifting vodka. Trying to exorcise her demons, she started talking. First to the media in Ireland and the U.S., then to the Belfast Project, and finally spilling everything in a 2010 documentary, I, Dolours.

In I, Dolours, she admitted to taking Jean McConville over the border, bringing her to an empty grave, and witnessing her execution. Her orders, she said, came directly from Gerry Adams. After the British government subpoenaed her interview from Boston College (so much for the college’s promise of confidentiality), Adams was arrested for Jean’s murder, but released after four days of questioning. During those four days, tremors ran through the region; it was only held together by a fragile peace.

In 2013, Dolours Price was found dead in her home from an overdose of sedatives and antidepressants – a desultory end to a woman of such passion. It wasn’t a suicide, according to the coroner, but rather “death by misadventure,” fitting for a woman who led a life of adventure and whose name means “sorrow.” At her funeral, Bernadette Devlin gave a eulogy that spoke to Dolours’ torment, “…forty years of cruel war, of sacrifice, of prison, of inhumanity… broke our hearts, and it broke our bodies and it makes every day hard.”

Now, a popular tourist activity in Northern Ireland is gawking at trouble spots of the Troubles where the blood hasn’t dried and the bitterness on both sides is palpable. Other former war zones – Rwanda, Bosnia, South Africa – have worked at reconciliation, but not so with the notoriously grudge-holding Irish.

Then along came Brexit, a profoundly stupid and wrong-headed move driven by the dying gasp of British Imperialism. Oddly, the U.K., or the “Mainland,” as it’s known to Loyalists, managed to have forgotten one of its extant colonies, Ulster. Brexit has placed a new fear in Northern Ireland: fear of a hard border, a return to fighting, soldiers, and sandbags, or at the very least, a soft border subject to endless custom wars without the protection of the E.U.

But there’s another possibility. A new referendum could result in Northern Ireland joining with the Republic to create a United Ireland. This would mean that, after 800 years, there would be no British presence in Ireland, something else Bobby Sands wrote about in “Stars of Freedom,” shortly before he died.

But this Celtic star will be born,

And ne’er by mystic means,

But by a nation sired in freedom’s light,

And not in ancient dreams. ♦

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co-writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

As the Pope wants to change the words “Lead us not into temptation” one wonders how effectual such a plea could have been regarding so many circumstances during The Troubles. In the Christian sense, no country, not even Ireland, can come before God. Victims deserve compassion. And, thoughts and opinions can be formed about prominent people and distinct characters of the conflict. But, a genuine humility must be assumed. With a fragile peace, indeed, Lord, lead us not into temptation, and allow a true wisdom to prevail, henceforth.

This article was extraordinarily exceptional. May God bless Northern Ireland.

May they rest in peace

God Save Ireland

I was hoping Irish America would leave a way to share your stories history and politics. Things like Telegram or twitter, Gab, Facebook, etc.

Delours was a soldier fighting for the right for an independent Ireland, completely . Mostly the young jad the courage she had.

The real Irish had no choice but to fight for independence due to British colonialism.

I have no doubt that her remaining years were full of nightmares and painful memories, even guilt for her role in the deaths of those she disappeared .

Those that criticise have never been forced to subjugate themselves to another foreign imperialist country,so there are no real meanings to their words.