All Hallows High School, a Catholic boys’ high school in the South Bronx, has a colorful history, from the sons of Irish immigrants who it was opened for to the minority students it now serves. Principal Seán Sullivan has made sure over the years that it is still one of the top Catholic high schools in the nation.

℘℘℘

When you walk through the doors of All Hallows High School, the first thing you’d better do is turn right. Or turn left. But you’d better turn, or else you’ll step on the beloved golden seal which bears the school’s name and motto – Pro Fiede et Patria… “For Faith and Country.”

As generations of graduates will tell you, walking on the seal is frowned upon.

“I remember my first year as vice principal,” current principal Seán Sullivan said during a recent visit to the school. “This poor freshman walked [across the seal], and I told him, ‘Don’t you see what that is? That’s the grave of Al Hallows, he’s buried there,’” Sullivan recalled with a laugh – before adding that the following day, the deeply remorseful boy returned with his mother, who was bearing flowers.

Which pretty much sums up what All Hallows has been about for over a century: families, respect, and a reverence for the past. “I’ve seen the first Irish Christian Brothers school,” Sullivan says, referring to the one opened by Edmund Rice on Waterford’s New Street in 1802. “It’s eerily similar to this one.”

Walking the halls of All Hallows can be a touch jarring: there are rows of blue lockers and classroom doors swung open, all familiar enough. But then there is the imposing, life-size marble statue of Blessed Edmund Rice at the end of the hall. (The case for Rice’s sainthood is currently being made at the Vatican.)

When the bell rings, the mostly black and Hispanic students in dress shirts and ties move quietly to their next class – occasionally stopping to shake hands with Principal Sullivan. But as they move, they walk past rows of photos of past school principals and presidents – almost all of them Irish or Irish- American.

Yet despite such obvious contrasts, Sullivan and other leaders at All Hallows note that today’s students have much in common with past graduates. And though you might think today’s students would have little interest in history in general, and Irish-American history in particular, a visit to the school proves otherwise.

“These kids really understand the historic ties,” notes Sullivan, whose office is teeming with photos, posters, statues, and other assorted knick-knacks reflecting his passions for Ireland and baseball – which is fitting since, after stepping off the 4 train at 161st Street, you have to walk past Yankee Stadium to get to All Hallows.

The school’s current building has been operating on 164th Street since 1930, located across from a park named after poet and journalist Joyce Kilmer – a high-profile supporter of the Irish independence movement which culminated in the 1916 Easter Rising. If you look closely at the building’s exterior, you will see images of George Washington as well as Saint Patrick. School sweaters bear the school’s mascot (the Gael) and colors (blue and white, reflecting the traditional sporting colors of Waterford), as well as a shamrock.

And when former Irish president Mary McAleese visited the school in 2012, she was understandably impressed by the school’s chapel: the altar’s marble is from Connemara, and the stunning stained-glass windows, by celebrated Irish artist Harry Clarke (1889-1931), are essentially priceless.

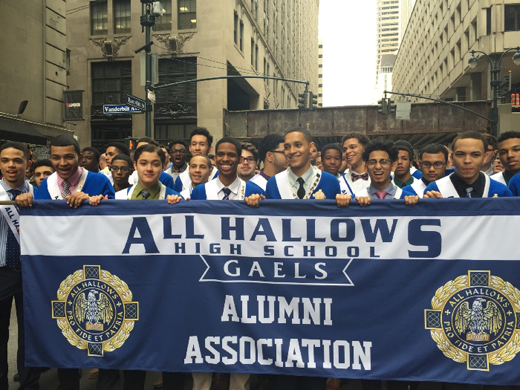

Two of the school’s annual highlights are also deeply Irish. First, of course, is the staff-student march up Fifth Avenue in the Manhattan St. Patrick’s Day parade. And second is the annual summer trip to Ireland.

Up to 12 All Hallows students – typically those who are most dedicated to their schoolwork as well as community service – go to Maynooth University every year to attend a 10-day conference on leadership.

“We always tell the kids: ‘Look, there’s going to be a culture clash,’” says Sullivan of the conference attended by students from all over the world – including troubled spots like Belfast and Palestine. “But very quickly…they find the commonality.”

He adds: “There’s just an ocean between them. That’s all.”

One All Hallows graduate, named Robert Rivera, liked Ireland so much he decided to attend college there. He’s currently enrolled at Maynooth University.

Sullivan’s parents came to the U.S. from Cork, and his mother was actually in Ireland while pregnant with him. But she flew back to have the baby in the U.S. “I don’t think she trusted the doctors over there,” Sullivan says with a laugh.

Aside from fundraising, Sullivan says the biggest day-to-day challenge is simply getting the students into the building every day. Adversity comes in many forms on the streets of the Bronx. All Hallows serves as a refuge from all that.

Along the same lines, one thing that has changed over the years, Sullivan notes, is the level of social and emotional guidance students receive, to go along with healthy doses of academics and discipline.

“[The students] know they have people here who are going to listen and who are going to help,” says Sullivan.

While visiting All Hallows, we also encountered a group of seventh-grade students from a charter school who may one day enroll at All Hallows, learn about Edmund Rice, and perhaps even visit Ireland. If they looked closely at the walls, they would have noticed not only Kelly green shamrocks, but also photos honoring “students of the week.” And amidst the many students with first names like “Kaheem” and last names like “Rodriguez,” they might also have noticed a name that could well have belonged to one of the former, white-haired principals – but in fact belongs to a current student: Phillip O’Flynn.

Immigrants: Then and Now

Martin Daly – “Marty” to everyone, with the exception of his Kerry-born parents – grew up in the Bronx, at a time when many of his neighbors and classmates also had parents from in Ireland. “So many of our parents were immigrants or first-generation,” says Daly, 67, a retired VP & director at CBS Network Sales. “Nobody had a whole lot of anything. But immigrant parents – I think you can make this generalization – they knew how important education was.”

Daly first attended St. Simon Stock grammar school on Valentine Avenue. Then, like so many fellow Bronx Irish Catholics, he went on to All Hallows High School on 164th Street, in the shadows of Yankee Stadium.

“All Hallows had a lot to do with helping me navigate those incredibly difficult mine fields everyone faces during the ages of fourteen to eighteen. And growing up in the Bronx, maybe there were even more,” Daly says with a laugh.

Daly graduated from All Hallows in 1970, yet remains active at the school. For the past decade, he has served on All Hallows’ board of directors, including the past five years as chairman. Daly – and many other Irish-American alumni who volunteer at the school – has watched as All Hallows’ neighborhood and student body changed drastically.

Currently, the 500-plus students at the all-boys school are over 95 percent African-American or Hispanic. And yet, in other ways, things have not changed all that much.

“We’re still serving the sons of recent immigrants to America… and still putting 98 percent of those young men in colleges,” says Daly. “They’re just from different islands…Puerto Rico, the Caribbean…It’s a bit of an educational miracle, really.”

Despite sitting in the poorest congressional district in the country, All Hallows has consistently been named as one of the top 50 Catholic high schools in the United States. It is the only city school in the Archdiocese of New York to have earned this distinction.

The school routinely places its entire graduating class in four-year colleges. The Wall Street Journal has called the school’s success in this area “stunning.”

If there is a “miracle” here, it’s not that schools such as All Hallows are doing this in 2019. The miracle is that they’ve been doing it for over a century.

And at a time when immigration is such a hot-button topic, All Hallows – whose sports teams are still known as the Gaels – reminds Irish Americans that, not so long ago, it was their own grandparents who were “high-needs.”

Ultimately, All Hallows illustrates all that can be accomplished when the dedicated children of yesterday’s immigrants work to harness the energy and passion of today’s.

“All Hallows is really true to the mission of Edmund Rice,” school president Ron Schutté (Class of ’74) said. “I grew up right around the corner,” adds Schutté, who also attended All Hallows grammar school. “When the Bronx was burning, we were still here…All Hallows really became my entire life.”

Across the decades, Schutté says, the one constant has been taking “the Edmund Rice mission and putting that into action.”

The Christian Brothers of Ireland

In order to fully appreciate the work that students and staff at Catholic schools such as All Hallows do, you need to go back in time to a farm in Kilkenny, to a time when America did not yet exist, and practicing Catholicism in Ireland was more or less a crime under the notorious Penal Laws.

That’s the culture into which Edmund Rice was born, in 1762. He was the fourth of seven sons, whose mother died in an accident – one of two tragedies that would profoundly alter his life and vocation. Rice initially became a successful merchant, and even got married. But then his own wife died, likely in an accident. (Many details of Rice’s early life have been lost to history.)

Adrift, Rice turned to religion, at first planning to go to continental Europe. But legend has it that, one day, Rice was talking to the sister of an Irish bishop, when they came upon a group of impoverished Irish boys.

“Would you bury yourself in a cell on the continent,” Rice was asked, “rather than devote your wealth and your life to the spiritual and material interest of these poor youths?”

Rice decided to devote himself to serving the poor and needy in Ireland, founding what would become known as the Christian Brothers of Ireland. During the first decade of the 19th century, Rice oversaw the opening of schools in Waterford, Dungarven, and Carrick-on-Suir.

Two centuries later, now known as the Congregation of Christian Brothers, the schools founded by Rice have served millions of “poor youths” in the U.S. and throughout the world.

All Hallows was the first Irish Christian Brothers high school to open in the U.S. in 1909. By then, the Irish in America had been through painful debates over religion and education. In the 1840s, powerful New York Archbishop “Dagger” John Hughes demanded government funding for a separate Catholic education system, in part because Irish immigrants faced such severe bigotry in New York’s supposedly non-denominational public schools. The message was clear: “Education was a way out of poverty,” as John Loughery writes in his recent book Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and the Making of Irish America. According to Loughery, Hughes once wrote that “the time has almost come when it will be necessary to build the school-house first, and the church afterward.”

In short, if immigrants and their children faced unprecedented adversity on the mean streets of New York, Boston, Philly, and Chicago, then only an unapologetically Irish and Catholic educational system would do.

Soon enough, Catholic elementary schools became the cornerstones of daily parish life. By the early 20th century, high schools such as All Hallows were thriving academically as well as athletically.

“Our job is to try and emphasize what is best about Catholic education…and stay true to our mission, which is to serve the poor and the marginalized,” says Schutté.

Or to use the precise words of what the school considers “Essential Elements of a Christian Brother Education”: to stand “in solidarity with those marginalized by poverty and injustice.”

And whether a student’s family hails from a small farm in Kerry, or the impoverished district along the Rio Ozama in Santo Domingo, All Hallows is now entering its second century of doing just that.

Learn, Earn, and Return

Now – as in the past – graduates of All Hallows serve as the best ambassadors for the school.

“An older kid would tell your mother and father what a great education you could get at All Hallows,” said Marty Daly. “The guys you played with on the street, [in] stickball or basketball… Word of mouth about the school is strong still today among, say, the Dominican community in the South Bronx or Harlem.”

“People who went to All Hallows tend to think very highly of it,” says Bill Wheatley (Class of 1962), a former executive at NBC News and current chairman of the All Hallows Foundation, which is charged with fundraising for the school. This is a crucial challenge, since most students are from modest backgrounds and receive financial assistance. (It costs All Hallows almost $11,000 to educate students, but the school only charges about $6,600 in tuition. Alumni, friends of the school, foundations, and other sources bridge that considerable gap.)

Wheatley grew up in the Parkchester section of the Bronx, where there were two parishes, St. Helena’s and St. Raymond’s, and monsignors were the “most powerful men in these very large communities.” He attended Catholic grammar school, where nuns taught classes with sometimes as many as 60 students.

“It was a very big change for me, going from the nuns to the Christian Brothers,” recalls Wheatley, who ultimately came to appreciate the, uh, stern discipline at All Hallows.

“I wasn’t an out-of-control kid, but I could use the discipline,” he said, adding, “[All Hallows] was instrumental in me having a sense of purpose. Teaching me…I could do well, as well as good, [and] make a contribution to society.”

Recently, All Hallows kicked off a new fundraising campaign, reminding potential donors of its mantra: “learn, earn, and return.” If that’s not convincing, school Principal Seán Sullivan has always remembered similarly precise words from a mother who explained why she chose to send her son to All Hallows: “You’re small. You’re safe. You’re successful.”

Edmund Rice could not have asked for more. ♦

Leave a Reply