An American pioneer of dance and an important figure in both the arts and history, Isadora Duncan was known as the “Mother of Modern Dance.”

“Sans Limites”

Oh, body swayed to music,

Oh, brightening glance.

How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

– William Butler Yeats, “Among School Children”

“She was a flame sheath of flesh made for dancing.”

– Carl Sandburg, Breathing Tokens, “Isadora Duncan”

“I dance what I am.”

–Isadora Duncan

℘℘℘

A great fire raged in her house when she was an infant. A fireman raced into the burning room and threw her out an open window into the arms of another fireman. So began the high-pitched drama that was the life of Isadora, a life that ended even more theatrically than the firemen’s game of catch. She lived for only 50 years, but in that short time, she founded modern dance, toppled Victorian sensibility, helped usher in the modernism of the early 20th century, and made some sensational headlines.

Angela Isadora Duncan was born on May 27, 1877 in San Francisco, the youngest of four children. Her mother, Dora, was a first-generation Irish American whose parents, Thomas Grey and Mary O’Gorman, were born, respectively, in Counties Tipperary and Offaly. After leaving Ireland, the devout Catholics sailed to America to travel across the plains, settling in Missouri. The family later moved to California, where Thomas went on to be a state senator and their daughter Dora went on to be a rebel. She married, at 21, something of a bounder, the much older Joseph Duncan.

Soon after Isadora was born, Joseph Duncan, a banker, was caught embezzling at work, while Dora discovered he had been embezzling at home too, pawning her jewelry, melting down the family silver, and splitting the proceeds with his girlfriend. No longer the good Irish-Catholic girl, Dora first divorced her husband, then her faith by embracing atheism. She forged ahead as a single mother and moved her four children to Oakland.

Dora supported the family by giving piano lessons while Isadora and her sister Elizabeth taught dance, and together the family held theatrical performances in their home. Mother and children were all remarkable, but they forever followed the lead of the youngest and most charismatic: Isadora. Bored by school, Isadora dropped out at 10 and taught herself at the public library. Even at that young age she had decided her future – she would be both a free spirit dedicated to the arts and a feminist who would never bear the “stigma of slavery” that was marriage.

The Duncan family continued to shock the Oakland Establishment. They were eccentric, owed money all over town, and worse, had taken to going barefoot and wearing odd costumes in public. The criticism didn’t bother the Bohemian brood one bit – food may have been scarce, but their home was filled with music and poetry. In her biography, Isadora wrote of facing down the moralists. “I suppose it was due to our Irish blood that we children were always in revolt against tyranny.”

She revolted against another, seemingly innocuous, form of tyranny: ballet. She called it a “living death,” rife with affectations, tutus, and stiff shoes. Her dance would be the gateway to the soul, “a different dance,” free, earthy, in communion with the elements. She believed she ran out into the storm, rain and sun, and became part of them. “The wind? I am the wind. The sea and the moon? I am the sea and the moon.” It would be in the tradition of the ancient Greek ideal, as unlike ballet as possible.

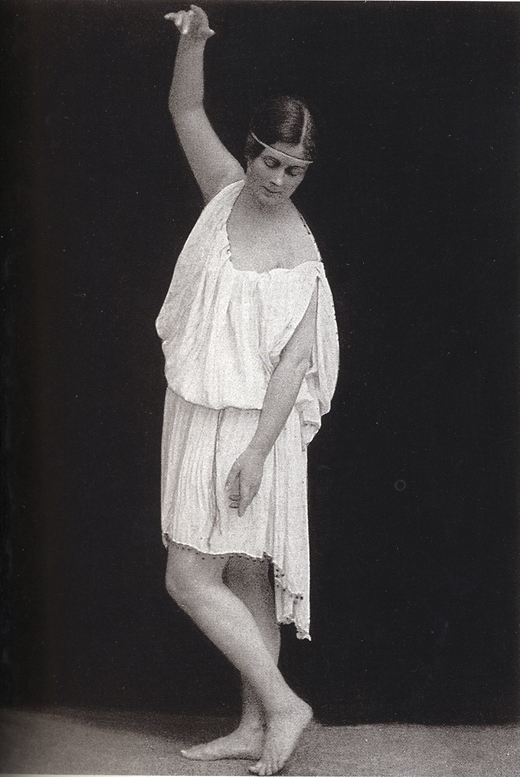

Isadora would stand alone at the back of the stage, barefoot, hair flowing and, in this corseted age, wearing a tunic often without benefit of underwear. She remained completely still until her long neck rose out of the muslin and slowly she began to move. Soon she was bounding across the stage, thrusting her knees, collapsing and rising, all to the music of Bach, Beethoven, Wagner, and Chopin. For inspiration she would, at varying times, draw on the writings and philosophy of Plato, Darwin, Nietzsche, and Walt Whitman; her dance was her own “Song of Myself.”

But Oakland was a backwater populated by provincials, hardly the place to stage a revolution. At 18, Isadora headed to Chicago, where she became so destitute, she sold her Irish lace for food. She finally found work in vaudeville, flouncing about as “Peppy Dora,” a cheesy act that failed to discourage the spiritual dancer. It was just another step to realizing her destiny as a great artist.

An impresario, Augustin Daly, saw something in Isadora and brought her to New York. After two years in his road company, mostly playing fairies, Isadora confronted Daly, “What’s the good of having me here, when you make no use of my genius?” He replied by putting his hand down her dress, she countered by quitting, and soon was performing in the homes of “the 400”: the wealthiest New Yorkers. But when a fire left her homeless, Isadora read it as a sign to leave New York; she hopped a steamer to London, traveling under her grandmother’s name, Mary O’Gorman.

In 1898, she arrived in London and again gave private performances where the elite now included royalty. The fresh, uninhibited, American girl captivated the fusty Victorians and won an influential patron, Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the muse of George Bernard Shaw. The actress, always reduced to sobs by Isadora’s performances, insisted “the barefoot dancer” experience Paris.

In Paris, in 1900, it was Isadora’s turn to sob, so overcome by passion at seeing her vision realized in the marble statues of Greek antiquity. Now inspired and emboldened, she captivated le tout Paris, the cultural center of the western world. Rodin proclaimed, “Sometimes I think she is the greatest woman the world has ever known,’’ while another sculptor spoke of seeing her on the stage, “When she appeared, we all had the feeling that God was present.” And God, in this case, was très chic (those tunics!), loved good food, and nights in the café. Her triumph was complete.

Isadora took her act, as it were, on the road. From 1899 to 1907 she was a sensation from great cities to the odiferous outposts of Russia and Eastern Europe – the dancer from America had become more famous than its president, Woodrow Wilson. She needed no translation, audiences saw her as the universal expression of the human spirit, life with all its ecstasy and tragedy.

Her Greek ideal now included the Dionysian or sensual tradition, perhaps, because at 25, she had lost her virginity. She became a feverish free love advocate, taking lovers from the aristocracy, the boxing ring, and the train, both passengers and porters.

In 1904 she met the great love of her life, stage designer Gordon Edward Craig. Craig describes her impact on the changing Western culture: “Into this dangerous world leapt Isadora possessed of immense courage… People called her a great artist, a Greek goddess but she was no such thing. I always thought how Irish she was – which means, how full of natural genius which defies description. She had the dream in her heart, the dream of the Irish…” Together they vowed to create a new world of the theatre, and together they overlooked the pesky fact of Craig’s wife.

In 1903 in Berlin she gave her most famous speech, a manifesto, on the future of dance. Doubtless thinking of herself, Isadora predicted dance would be for the “free spirit…whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together.” Her feminism ran throughout the manifesto as she anticipated the “body of the new woman more glorious than any woman that has yet been.”

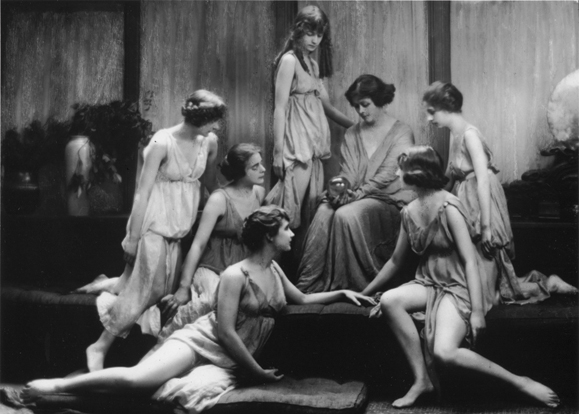

When the American Athena finally made her pilgrimage to Greece, she kissed the ground, touched the sacred marble of the Acropolis and made plans to educate young children. Her original school, in Germany, embraced her philosophy, “Let us first teach little children to breathe, to vibrate, to feel” and her radical concept – the solar plexus was the source of all the body’s energy and movement. She loved all her students, particularly her pets, the talented girls known as the “Isadorables,” later adopting them and giving them her last name.

Isadora was a woman with a fierce maternal drive, as evidenced by the feelings she had for her Isadorables, but more than anything she wanted a child of her own. She approached George Bernard Shaw: “Will you be the father of my child? A combination of my beauty and your brains would startle the world.” His Shavian response: “I must decline your offer with thanks, for the child might have my beauty and your brains.”

In 1906 she did have a child with Craig, named Deirdre, evoking Irish mythology and “Deirdre of the Sorrows,” a reference that would prove painfully prescient. Two years later, as she and Craig were getting increasingly competitive, Isadora booked a Paris engagement and, taking Deirdre, left Germany. After one performance, a tall, handsome, and smitten stranger walked into her dressing room. Paris Singer, heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, had a compelling pick-up line: “I’m here to help, what can I do?” Apparently a lot. He gave her an estate to build a school dedicated to art, an apartment in Paris, and, best of all, in 1910, a son, Patrick. While she had great affection for Singer and appreciation for his generosity, she refused to marry him.

Isadora now had everything: fame, great wealth, a devoted partner and two beautiful children. But she was Irish, she was superstitious, she knew the risk of drawing too much attention to life’s deepest joys. So began a sense of forboding that wouldn’t leave – during her performances she began to smell funeral flowers.

In 1913, while Isadora and Paris were having lunch, the chauffeur driving the children stopped to crank the engine without securing the break. The car bolted forward into the Seine, drowning Deirdre (six), Patrick (three), and their nanny. It was a death blow for Isadora too, killing any “hope of a natural, joyous life for me”; she longed for “annihilation in death.’’

Isadora distanced herself from Singer, who always remained devoted, while Edward Craig failed to attend his daughter’s funeral. She turned to her family, and they retreated to Italy where, in a desperate attempt to have another child, she got pregnant by a local artist only to have that baby die a few hours after its birth, “A triple fountain of tears, milk and blood flowed from me.”

Grief begat spinning: she went to New York to build schools and theatres, ventures that failed. She had a rift with her family – even the Isadorables, save Irma Duncan, deserted her. Adrift, she didn’t notice or care that as her wealth diminished, her absinthe intake expanded, as did her waistline. She had a few lesbian affairs, most notably with Mercedes de Costa, the sometime inamorata of Garbo and Dietrich. In addition to Mercedes, Isadora had become infatuated with communism.

In 1921, Isadora took herself to Moscow, the first American granted a visa to the fledgling Soviet Union. She set out to start a children’s dance school, bring her revolutionary art to revolutionaries and “dance for the masses.” Sulking in the masses was poet Sergei Essenin, who shared Isadora’s passion for creativity and vodka. He was 18 years younger, and, overturning her lifetime aversion, she married him, rationalizing, “it was easier to marry him than adopt him.”

Needing money, Isadora embarked on a tour of America, bringing along her little madman of a husband – she would dance, then trot him out to recite his poetry, in Russian, a language few Americans knew. Essenin, always drunk and usually violent, proved years again of his time by trashing their hotel rooms. Isadora, not to be outdone, bared one brazen breast in Boston while draping the rest of her body in commie red, a scandal that rocked Beantown.

She received a horrifying review from George Balanchine, “To me it was absolutely unbelievable – a drunken, fat woman who for hours was rolling around like a pig.” Her reputation in tatters, she left her mother country, announcing, “Good-bye America, I shall never see you again!” She never did. Essenin went back to Moscow where he later slit his wrists, wrote a poem in his own blood, and finally expired.

Losing her children was the cause of the wreckage that defined the last 14 years of her life. But, in truth, she was always an excessive personality, always driven by impulse, a woman of abandon without self-control. Let’s not forget her motto was “Sans Limites.” Now, with no limits, there was nowhere to go but down, and go down fast.

During her final years, she was a grotesque figure, wandering between Paris and the Riviera, notorious for public drunkenness and stalking young men. She lived on handouts from former colleagues and was given to self-deprecating quips, “I don’t dance anymore, I only move my weight around,” or “Men and potatoes have ruined my life.” Most of her friends deserted her, leaving only her most loyal girlfriend, Mary Desti, mother of great American director, Preston Sturges. When Mary told Isadora she was destroying her legend, needed to cut back on her drinking and especially lay off the boys, gently adding that they weren’t interested in a woman of her age, Isadora stormed off in a huff.

They must have made up, because Mary was with her in Nice when Isadora spotted a young driver in an open-air Bugatti sports car. Being Isadora, she hopped in, and, prescient for the last time, shouted to her friends, “Adieu, mes amis, je vais a la gloire!” – “Goodbye, my friends, I go to glory!” She took off and moments later, the fringes of her signature scarf caught in the spokes of the back tire, instantly breaking her neck.

Isadora Duncan fought Puritanism, championed feminism, celebrated the female body, and created a new art form. Today her legacy is manifest, evident in contemporary choreography, dance schools, and yes: ballet. She even managed to exceed the many and extravagant controversies of her life with her death, as flamboyant as it was tragic, almost as if she had designed it: Irish mysticism had fused with Greek tragedy – the dancer had become the dance. ♦

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co- writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

Leave a Reply