Irish America looks back at the legacy of St. Patrick’s Battalion, an honor-bound group of Irishmen that championed the cause of the smaller Mexican force against the might of the American army during the Mexican-American War.

“You have to understand that we Mexicans and Irish are very sentimental,” said the slight, grandmotherly figure, leaning forward in a high-backed living room chair and choosing her words carefully. Short of stature, wiry, and extremely lucid for her 81 years, Patricia Cox, the noted Mexican novelist, was explaining why nearly 250 immigrant Irish soldiers deserted from the U.S. Army during the 1846 war with Mexico and joined the enemy forces, even though the latter were losing battles. A year later, just as Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle fell to the Americans, U.S. Col. William S. Harney (known in the ranks as a “right hard hater”) gave the sign to hang 30 prisoners of the rebel St. Patrick’s Battalion, led by Galway-born Captain John Riley. The war was over, and Mexico was forced to cede half its territory to the colossus of the north.

Cox’s use of the word “sentimental” translates poorly into English. In Spanish, it connotes compassion, solidarity, and deep personal bonding, rather than superficial feelings. During the two-year conflict, the immigrant deserters forged a strong alliance with the Mexicans. But Anglo-American historians insist it was not solidarity but drink, disorderly behavior, and opportunism that drove the immigrants into the enemy’s ranks. In a sense, the scholars’ conclusions are understandable. By the 1840s the stereotype of the drunken and combative Irishman had taken root in the U.S. consciousness, later hardening into vicious cartoons showing Paddy and Bridget as crude, hapless, simian brutes, congenitally incapable of assimilation into white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant society.

The memory of the Batallón de San Patricio might have sunk into oblivion had it not been for a visit Cox made to the former Franciscan friary of Churubusco in Mexico City in the 1950s. A custodian, mindful of her Irish ancestry, showed her a stone engraving commemorating a number of Irish volunteers who defended the convent/fortress as U.S. Gen. Winfield Scott’s army pushed into the city.

Encouraged by her husband, sculptor Lorenzo Rafael, Cox thoroughly researched the story and published the novel Batallón De San Patricio. The book earned her critical acclaim, a citation from President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and has helped strengthen the bonds of affection between Mexico and Ireland.

℘℘℘

COMMEMORATION

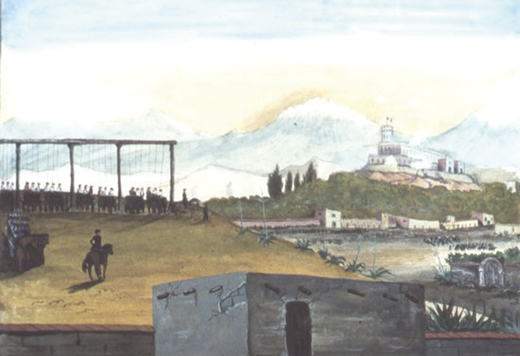

Those ties surface annually with the commemoration of the Batallón de San Patricio at Mexico City’s San Jacinto Plaza, where Gen. Scott ordered 16 of the deserters to be hanged on September 10, 1847. The square is now a peaceful park, punctuated by artists’ exhibits and surrounded by trendy restaurants. A cross-section of the city’s Irish community and local dignitaries watch solemnly as a military band plays the Irish and Mexican national anthems. On the crowd’s periphery, an American tourist with a video camera asks what the Irish were doing in Mexico in 1847. His wife tells him to hush.

A police honor guard places a floral wreath near a stone plaque commemorating the men who marched with Captain John Riley. As Stephanie Counahan (Cox’s daughter-in-law) calls out the name of each soldier, the crowd chants, “Murió por México” (“He died for Mexico”). After a few speeches, the ceremony draws to a close with a drum roll and the playing of reveille. Slowly, the flags are folded, including one dedicated to Riley.

Among the onlookers is Denise Ogden, a Dublin native who has lived in Mexico City for 20 years. “I think this ceremony is important,” she says, carrying a two-year-old girl in her arms and flanked by two other daughters. “It shows how Mexicans were helped by other nations and how much the Irish care about justice and peace throughout the world.” Beside Ogden is missionary Sister Noreen Walsh, who says her cousin Rory Lavelle of Galway has spent years researching John Riley’s roots. “He [Riley] was very aware of injustice and oppression and I think it was easy for him to change over and fight with the Mexicans,” Walsh said. “I’m speculating, but I think John Riley must have had some sense of God as well, and some sense of humanity.”

Standing behind Walsh are two young Irish businessmen, Mike Nolan and Des Mularkey. “It makes me proud when I think about the St. Patrick’s Battalion and the affinity between the Irish and the Mexican people,” says Nolan. “People here remind me that one of the members of the battalion was a Nolan. It’s a great story of martyrs, of people fighting for a just cause – and to think they were Irish, well, it makes you feel good.” Mularkey nods in agreement. “It’s great that the Irish have done something here and we are remembered for it,” he adds, “So you do get a few goose pimples when you hear the Irish national anthem played so far from home.”

Later, Erwan Fouere, the European Community’s Irish-born ambassador to Mexico, explains that several Irish military figures made their appearance in Latin America during its wars of independence. “These countries suffered the same problems the Irish faced – foreign domination, foreign control,” he says, his desk bordered by the flags of Mexico and the European Community. Fouere recites the names of the Irish liberators: Daniel Florencio O’Leary in Venezuela, Simón Bolívar’s chief lieutenant and biographer; Admiral William Brown, a Cork man who founded the Argentine navy; and Bernardo O’Higgins, the liberator of Chile. ‘‘The San Patricios were in the same tradition,” Fouere says. “The majority were executed for their pains, but they became a symbol of Mexican independence and defense against imperialism.”

℘℘℘

AN UNPOPULAR WAR

By most accounts, the U.S.-Mexican war was a pure and simple land grab. President James K. Polk and other expansionist politicians believed Mexico stood in the way of a U.S.-dominated continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts. Ironically, the so-called doctrine of Manifest Destiny was formulated by John O’Sullivan, the Irish-American editor of the Democratic Review, who wrote: “It is our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence of our yearly multiplying millions.”

After winning its independence from Mexico in 1836, Texas claimed that its southern border was the Rio Grande, while the Mexicans insisted it was the Nueces River, 150 miles to the north. Ten years later, spoiling for a fight, Polk ordered Gen. Zachary Taylor’s army to encamp on the banks of the Rio Grande. When a skirmish developed with Mexican troops, the clarion call was sounded: “American blood has been spilled on American soil!” Congress declared war and from Sacramento, California to Veracruz, Mexico was invaded by five U.S. armies of occupation.

Anti-war sentiment was strong. Abraham Lincoln vigorously opposed the conflict and challenged Polk to show him exactly where American blood had been spilt. Ulysses S. Grant called it “the most unjust war ever waged by a stronger over a weaker nation,” and former president, then-congressman John Quincy Adams died of a heart attack on the floor of the House while urging U.S. soldiers to desert rather than serve.

Labor historian Philip Foner reported that Irish workers demonstrated against the war, and in New England, a workingmen’s association announced their refusal “to take up arms to sustain Southern slaveholders.” Yet thousands of destitute immigrants enlisted when offered 100 acres of public land and three months’ advance pay to help support their families.

The jingoists, however, shouted loudest and had their way. The New York Herald trumpeted, “The universal Yankee nation can regenerate and disenthrall the people of Mexico in a few years… We believe it is a part of our destiny to civilize that beautiful country.” According to historian Cecil Robinson, Mexico was seen as a petty dictatorship – as “a stronghold of Roman Catholic superstition and the dwelling place of a racially inferior people who needed to be conquered by a superior country.”

In the end, Mexico’s poorly prepared conscripts were no match for the better-trained and -equipped U.S. forces. From the battle at Palo Alto near Fort Brown, Texas until the final siege at Chapultepec, the Yankees outflanked and outgunned their opponents. Still, as the editors of the Chronicles of the Gringos conclude, the war was hell for both sides: “The Americans…did not like the army, they did not like war, and generally speaking they did not like Mexico or the Mexicans. This was the majority: disliking the job, resenting the discipline and caste system of the army, and wanting to get out and go home.”

℘℘℘

ORGANIZING THE BATTALION

Of all the characters in the Mexican-American War, John Riley remains one of the most colorful. Described as tall, blue-eyed, broad-shouldered, and fearless, Riley first deserted from the British army in Canada. Later he joined Gen. Zachary Taylor’s U.S. forces, ordered by President James K. Polk to occupy a disputed border area in Texas near the Rio Grande. This provocation led to the outbreak of hostilities and to a declaration of war against Mexico on May 13, 1846.

After six months in the U.S. Army, Riley organized more than 150 deserters and persuaded the Mexican forces to accept them as a foreign legion. During the war, their number grew to more than 450. Most were Irish, but there were other immigrants with names like Vinet, Schmidt, Klager, and Longenheimer. Riley dubbed them the San Patricio Battalion and fashioned a flag emblazoned with a crudely drawn figure of St. Patrick, a shamrock, and a harp. Several motives are given for the U.S. Army’s nine-percent desertion rate during the war, the highest in U.S. military history. Anglo-American officers often treated their subordinates with contempt, cruelty, and racism. A common punishment for trivial offenses was “bucking and gagging,” or hanging a soldier by his wrists with a gag in his mouth. George Ballentine, an Englishman in the U.S. Army, cited this as one reason why the San Patricios deserted. Discipline was lax, and scores of drunken volunteers from Arkansas, Tennessee, and Texas had to be sent home after raping women, pillaging, and burning entire Mexican villages, including churches. Meanwhile, morale deteriorated with harsh living conditions on the South Texas plains: leaky tents in the cold winter, searing summer heat, insect bites, diarrhea, and dysentery. More than 1,000 men died of these diseases even before Taylor’s army crossed the Rio Grande.

The Mexican generals, conscious that 50 percent of the U.S. troops were Catholic immigrants, sent handbills to Fort Brown (now the border town of Brownsville, Texas) urging the men to join the Mexican army, offering them better pay and a promise of 320 acres of land. Riley and his companions were among the earliest deserters. Their first recorded combat was in the defense of Monterrey, now one of Mexico’s most industrialized northern cities. Later, as artillerymen, they spearheaded a column of Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s army that engaged the Americans at Buena Vista, a few miles south of present-day Saltillo.

Twenty-three men from the battalion died in the encounter – at least five were decorated for bravery. The Mexicans were winning, but for some unexplained reason, General Santa Anna suddenly withdrew his forces, ceding the victory to the Americans. Francisco Ollevides, the 80-year-old Dean of Saltillo’s historians, said sternly, “We don’t know what happened with Santa Anna, but one thing is certain – Mexico has never repaid its enormous debt to the Irish. After all, they gave their lives for Mexico.”

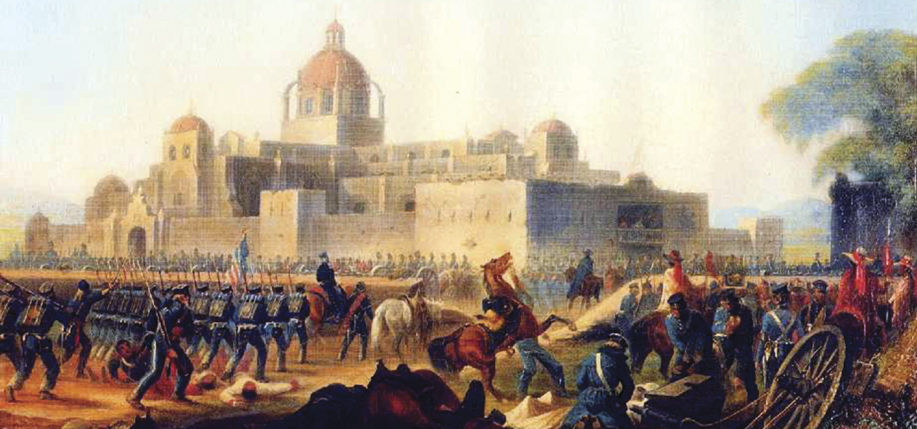

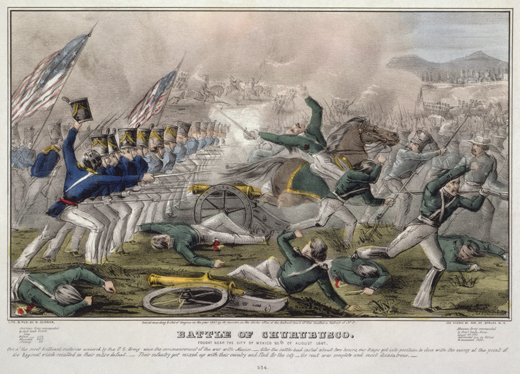

A year after Buena Vista, fortified by more deserters, the San Patricios helped defend the Churubusco convent against Gen. Winifred Scott’s advance into Mexico City. The Mexican soldiers, unable to withstand the gringos’ withering artillery fire, attempted to surrender. But each time they raised a white flag, Riley and his men pulled it down.

℘℘℘

CAPTURE AND PUNISHMENT

Later Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna insisted that if he’d had a few hundred more men like those of the Foreign Legion of San Patricio, he might have won the war. When the convent/fortress fell, scores of San Patricios lay dead. Eighty-five were captured and 72 underwent trial at two separate court martials. Gen. Scott authorized capital punishment for 50 prisoners, pardoned five men, and reduced 15 sentences, including John Riley’s, from hanging to branding and whiplashing, since they had deserted before war was declared.

Historians recount that during their trials none of the San Patricios gave ideological or religious reasons for deserting, blaming their actions instead on drink or coercion by the Mexican army. However, these scholars fail to explain both the nature of their legal defense and the kinds of testimony the court would permit. Peadar Kirby notes in his book Ireland and Latin America that the defendants were obviously trying “to make desertion less of a crime than it might appear.”

During a short armistice, Mexican military authorities and the archbishop of Mexico City pleaded on their behalf, but Gen. Scott turned down both petitions. In his book Sword and Shamrock, Robert Miller quotes an eyewitness account of the floggings and executions by Captain George Davis. Wondering why the men had not died under the whiplashes, Davis compared their backs to pieces of raw beef, “the blood oozing from every stripe as given.” Later, he observed the hangings of 16 prisoners at San Angel. Two men with nooses around their necks stood in each of eight mule-drawn wagons under a wooden scaffold. At the tap of a drum, the carts lurched forward, swinging the men off. Meanwhile, five priests prayed for and administered the last rites to seven who were practicing Catholics. Afterward, Riley helped bury several companions under the gallows.

Two days later, with the hanging of 30 more San Patricios and the fall of Chapultepec Castle, the war concluded. Months later, with the signing of a peace treaty, Riley and his mates were set free. After the war the battalion regrouped into the Mexican army as two infantry units and Riley, now a colonel, became involved in a failed attempt to topple the government and spent a few months in jail.

Eventually, the battalion was disbanded and several members left Mexico from the port of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico. Others settled in Mexico but left few records. According to Miller, Riley remained in the army until 1850 when he was discharged in Veracruz with $800 in back pay. There his trial ends, and one can only speculate whether or not he returned by ship to his native Galway.

Despite the verdict of many historians, who consider the Batallón de San Patricio a bizarre aberration in U.S. military history, these men have earned a prominent place in the hearts of the Mexican people. Perhaps Gonzalo Maninez, a prominent Mexican film director, best summed up those feelings. Standing recently near the embattlements of Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City, Martinez said, “In every dirty war, there are a few good men who stand up for what is right. The U.S. invasion of Mexico was such a war, and the San Patricios were those kinds of men.” ♦

This article originally appeared in Irish America‘s May / June 1993 issue.

Martin Lydon on that wall, that was my Grandfather’s name,

Hi Mark would you be interested in coming onto the Irish Transna na Tire zoom series to give us a talk on this subject.

Many Thanks Stephen

I’m a Texan. I’ve been to Churubusco convent a couple times. I’ve also been to San Jacinto Plaza. I’ve wondered why Irish conscripts were not released from service duty sonce US volunteers were released by Genl Winifred Scott before arrival at Puebla. Mexico City lives up to ever’thg ever uttered about it.