John Dearie may not remember the specific year, but he remembers a very small, very important detail about one New York City St. Patrick’s Day parade in the late 1980s. “I remember seeing all of these people marching by, county after county. It had to be tens of thousands of men and women marching by. And they were all wearing this ribbon.”

Dearie – a longtime New York state lawmaker and 2019 inductee into the Irish America Hall of Fame – is referring to a ribbon that was specially designed so that Irish-American groups could express their support for the appointment of a special envoy to Northern Ireland. Whatever differences of opinion all of these Irish groups may have had at the time – and there were surely plenty – they all wanted then-president Ronald Reagan to know that the U.S. should play a bigger role in efforts to bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

IRISH AMERICA INVOLVED

At the time, this seemed a very ambitious – even unlikely – hope.

The situation in the North was terrible, with hundreds dying in political violence every year. Meanwhile, the U.S., especially during the Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher years – often cited its “special relationship” with Great Britain, when defending its hands-off approach to the North.

And yet, within a decade, not only would a special envoy be named (the one-time U.S. Senator from Maine, George Mitchell), but the historic Good Friday Peace agreement would be signed.

John Dearie – a Bronx native, with roots in Cork and Kerry – played a key role in making it all happen.

“When America got involved,” Dearie recently told Irish America, “when a fella from Arkansas appointed a fella from Maine, we were able to bring about significant developments.”

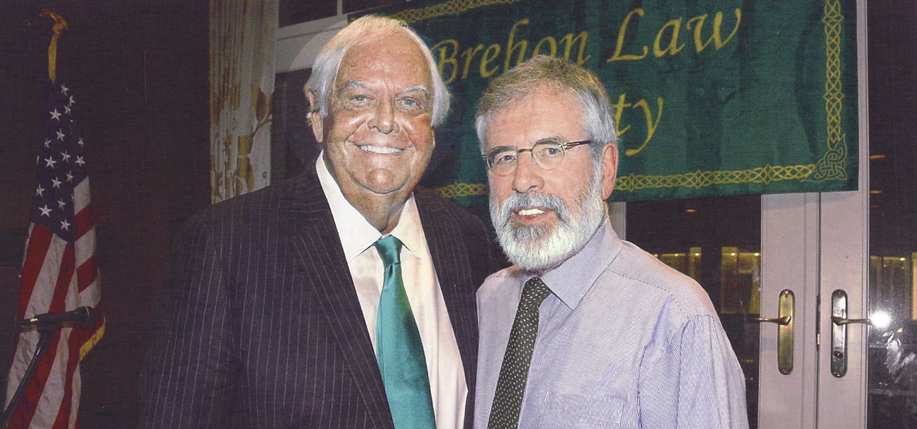

Dearie was referring to President Bill Clinton, elected in 1992, after promising the Irish-American community that America would play a bigger role in the peace process. That included not only appointing Mitchell, but also agreeing to issue a visa to Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams, so that he could travel to America and lobby for a prominent nationalist role in the negotiating process.

Adams has been a mainstream figure for decades now, so it’s hard to remember when he was a pariah in the eyes of many British officials, and even some influential Irish Americans.

But when Adams himself looked back on these events, he could not leave out the important role John Dearie played.

“In April 1992, a well-known Irish American, John Dearie, organized a forum on Irish issues in Manhattan’s Sheraton Hotel for Democratic presidential hopefuls Jerry Brown and Bill Clinton,” Adams recalled in his book A Farther Shore: Ireland’s Long Road to Peace.

Adams added: “Asked by one of the panelists if he would appoint a peace envoy for the north, Clinton said he would. When Martin Galvin of NORAID (an American support group for the republican cause) asked the presidential candidate if he would authorize a visa for me and other Sinn Féiners to visit the U.S, Clinton replied, ‘I would support a visa for Gerry Adams.’ Clinton went further and endorsed the MacBride Principles. His response received loud applause.”

Many credit these Irish-American presidential forums with putting Northern Ireland on the U.S. political agenda. And since, in Dearie’s opinion, it has dropped off the radar in recent years – despite the serious threat Brexit represents to the situation in the North – he says the 2020 election is the right time to bring such forums back.

PARENTS’ PRIDE

Dearie says he is particularly proud to be named into the Irish America Hall of Fame alongside the likes of Adrian Flannelly, with whom he discussed so many important Irish issues of the day on radio.

“There are few things in my adult life that are more significant than this,” Dearie said. “It’s something I treasure.”

Both of his parents have passed, but Dearie knows they would be particularly proud of this honor.

“My dad was one of the most humble people that I can recall…but they both would be very proud. We were not people anticipating recognition for anything. We were Bronx folk and just happy to do the right things.”

John Dearie’s road to international peace negotiator began on the streets of St. Raymond’s parish in the heavily Irish Parkchester section of the Bronx.

His father was a union plumber, while his mother worked for an advertising company.

“We actually had a piano in our two-bedroom apartment. And groups of friends of my family would come to the apartment and, literally for hours, we had a couple of women who were remarkable piano players. And we would just sing Irish songs.”

Dearie attended what was then Manhattan Prep High School, run by the Irish Christian Brothers on the campus of Manhattan College.

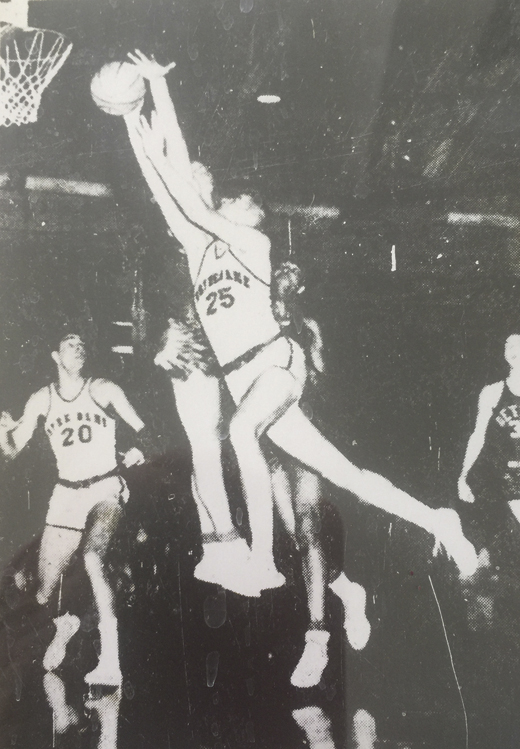

At a time when Irish Americans from urban Catholic schools were some of the top basketball players in the country, Dearie was an all-city player.

He wound up with dozens of athletic scholarship offers – but one stood out more than others.

“When the coach at Notre Dame came to our apartment and offered me a (basketball) scholarship… Once I heard Notre Dame, that ended everything for me. It wasn’t a hard choice.”

Dearie played against a number of future NBA Hall of Famers in the late 1950s and early 1960s, averaging 10 points and eight rebounds a game.

After Notre Dame, Dearie attended business and law school, also working at the United Nations, giving him his first real taste of the political process and the international scene.

BACK TO THE BRONX

But when a New York State Assembly seat in Dearie’s old neighborhood opened up, he decided to enter politics. At the time, the burning issue of the day was U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Fellow Irish-American assemblyman Sean Walsh, who represented Fordham, turned Dearie onto issues related to the Irish on both sides of the Atlantic.

“In the ’70s and ’80s, there were a tremendous number of Democrats and Republicans, in the state senate and in the legislature, who were Irish-American,” Dearie recalls, recounting the numerous issues the American Irish Legislators Society took on.

There was the controversy over Joe Doherty, an I.R.A. volunteer who escaped from a Northern Ireland prison and fought extradition for years in the U.S.

Then there was the implementation of the MacBride Principles, which ensured that U.S. companies doing business in Northern Ireland did so without contributing to discrimination.

Dearie grew upset with powerful politicians nodding to the Irish-American community by merely wearing a green tie on St. Patrick’s Day. He believed it was up to Irish Americans to put pressure on elected officials to address issues that actually mattered.

Recalling his own first visit to Belfast in the early 1980s, Dearie said: “There was still a military presence on the commercial streets as I recall. There was a lot of tension…you could feel. I felt there was an uneasiness and tension that was very measurable.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Now, after two decades of tenuous peace that Dearie helped bring about, fear is again palpable on the streets of Belfast.

“It’s worrisome,” Dearie says bluntly.

As The New York Times noted recently: “In the tortured history between the two island nations, Brexit is just the latest in a long line of perceived slights the Irish have suffered at the hands of the British. And now, with the possible exception of Britain, no country stands to lose more from Brexit, and particularly from a damaging ‘no-deal’ departure, than Ireland.”

At the center of this controversy is the question of what kind of border Brexit may require between the Republic of Ireland and the North.

“Not only (could Brexit) be economically destructive, if it results in the return of a strong international border, it could undermine the hard-won 1998 peace deal with Northern Ireland, known as the Good Friday Agreement,” the Times added.

Dearie believes greater Irish-American involvement could help avert the worst-case Brexit scenario. Which is why Dearie says other veterans of Irish-American affairs, such as congressmen Richie Neal and Eliot Engel, as well as former congressman Joe Crowley, are looking to bring back Irish-American presidential forums for the 2020 election.

More broadly, Dearie – who added that he is expecting to visit Ireland in April – believes it is important for a new generation of Irish Americans to reconnect with their culture.

“We need to get young people involved in AOH chapters, we have to find groups with younger Irish Americans… How do we reach a Friendly Sons (type) organization that has contact with (Irish Americans) and try to deliver the message about the importance of things like Brexit, the MacBride Principles, Irish visas. How do we get that message home?”

He added: “There’s a whole generation that has not heard the message: America has a vital role to play.” ♦

_______________

Click below to see John Dearie’s remarks upon being inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame at the Pierre Hotel on March 14, 2019.

Leave a Reply