The famous British Army surgeon was actually an Irish woman.

℘℘℘

Dr. James Barry was born in County Cork as Margaret Anne Bulkley, the daughter of Jeremiah and Mary-Ann (neé Barry). Accounts vary on the year of her birth but whether it was 1789 or 1795, women were denied a formal education. Her father was a feckless grocer who lost his business, landed in debtors’ prison and last seen on a convict ship to Australia. Alone and penniless, Margaret and her mother emigrated to London where they lived with her uncle, James Barry, a successful painter, progressive thinker and major eccentric.

Uncle James had a coterie of rich, radical patrons including General Francisco de Miranda and David Stuart Erskine who became impressed and obsessed by Margaret’s intelligence. Devout feminists all, these de facto godfathers vowed to get her a medical degree especially since Miranda’s soldiers back in Venezuela needed a doctor. Together they devised a plan, a trope that dates back to Greek Literature – Margaret Anne would dress as a man. Taking the names of her uncle and godfathers, Margaret Anne Bulkley became James Miranda Stuart Barry. Now she was a he.

With taped breasts and a heavy overcoat lined with fluff, the newly christened James Barry enrolled in the University of Edinburgh. He impressed everyone with his brilliant mind but became something of a curiosity. There was the baby face (absent an Adam’s Apple), height (barely five feet), squeaky voice and bursts of violent temper. Rumors spread, not that he was female, but a pre-pubescent boy. He received his MD at the tender age of 22, noting in his final thesis, he was a “man of understanding,” something he remained for the next 56 years.

Even when he was Margaret Anne Bulkley, James Barry would announce to anyone in earshot, “Were I not a girl, I would be a soldier!” By the time he graduated, General Miranda was dead and so was Barry’s Venezuela plans. After receiving his Royal College of Surgeons diploma, he entered the British military, passing what must have been a cursory army physical. It was 1812 and Dr. James Barry, army surgeon, was appointed Medical Inspector for Cape Town South Africa.

Something of a health nut, Dr. Barry was a teetotaler and vegetarian who kept a pet goat for its milk. Always at odds with his superiors, he raged at them about unsanitary hospital conditions and kept raging until he singlehandedly revolutionized healthcare in Cape Town. Revolutionary too was his open-mindedness – he treated everybody, not just wealthy whites but colonials, slaves, the poor, mentally ill and prisoners. Throughout his career, he had an odd affinity for lepers, treating them with almost saintly compassion.

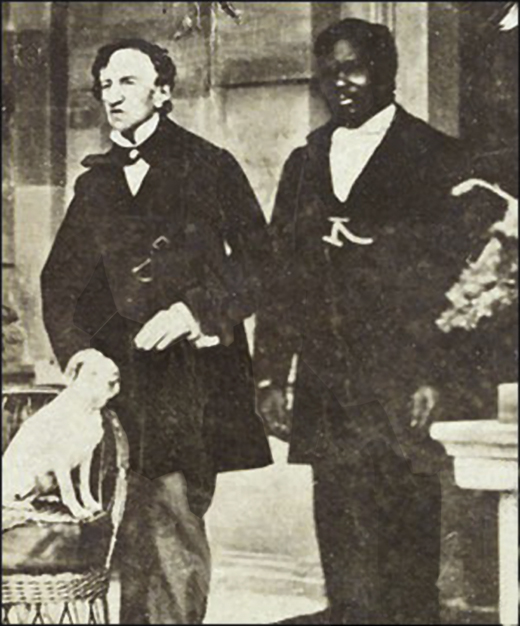

His patients adored him but not so much his co-workers and administrators who found him foul-mouthed, short-tempered and, considering his looks, full of an absurd vanity. His short fuse had much to do with the effort he undertook to look and behave as a man. Barry had by his side for 50 years, a West Indian manservant, John Danson, who supervised the makeover. John – who, it should be noted, never saw Barry naked – would obscure curves, strategically place padding and add height, courtesy of 3-inch shoe lifts. The manservant set aside extra primping time since the doctor was, ironically, a ladies’ man, thanks to his light-footedness on the dance floor.

His toilette over, Dr. Barry emerged in a scarlet jacket, a plumed hat covering the wig that covered his frizzy red hair and a saber draping his tiny physique. The saber was essential since Barry, quick to take offense, would challenge anyone to a duel or threaten to cut off the villain’s ears if he heard a slight against his low stature or high voice. He and John always traveled with Barry’s beloved poodle, Psyche, and a menagerie of small animals.

Dr. Barry proved unstoppable. He developed a plant-based treatment for syphilis and gonorrhea, promoted the novel concept of clean water and a healthy diet, introduced the smallpox vaccination to the colony, twenty years before it was introduced in England. At a time when doctors avoided lady parts and delivering babies, Dr. Barry was, not surprisingly, a most popular OB-GYN. He performed the first successful Caesarean section, meaning both mother and baby lived, in the British Empire.

And there was a scandal. Cape Town gossip had it that he was having an “unnatural” affair with the colony’s governor, Lord Charles Somerset, a man Barry once called “my almost only friend.” Vulgar posters announcing the governor was “buggering Dr. Barry” or referring to the doctor as his “little wife” were everywhere. Rumors intensified when Barry moved into Somerset’s estate especially as Somerset had politically and monetarily backed the doctor’s reforms. As homosexuality was a serious crime, the Crown set up an investigation; both men were exonerated but soon afterwards, the doctor, likely heartbroken, left Cape Town. It was the only time Dr. James Barry found romance and if the relationship was sexual it would have been…curious.

After Cape Town, Barry served as Medical Inspector in posts throughout the Empire from Jamaica to Malta to Canada. Wherever it was necessary, the cross-dressing, globe-trotting surgeon established a leper colony. Wherever he was posted, he fought for sanitation and universal healthcare while remaining insubordinate to his superiors. He went AWOL in Jamaica saying he needed a “proper haircut.” In St. Helena, he bypassed top officers to petition the Home Office for medical supplies and was summarily court-martialed for “Conduct unbecoming an Officer and a Gentleman.”

His career trajectory zigged and zagged. Stationed in Malta, Dr. Barry again found himself in good favor when the Duke of Wellington commended him for instituting public sanitation and preventing a typhus epidemic. He was promoted to the highest rank an army doctor could reach, Inspector-General of British Hospitals, the equivalent of Brigadier-General. Lord Raglan, commander of the British Forces during the Crimean War, asked the now-eminent doctor to pay a “social visit” to the battlefield.

Even though he was on leave, Dr. Barry went to Scutari, the site of an infamous hospital where more soldiers died of infection than battle wounds. It was also the site of his infamous fight with Florence Nightingale, pet of Queen Victoria. In his salty style he upbraided Nightingale about her hat or lack of, she called him a “brute” and so began a mutual and a lifelong hatred. Nightingale did improve sanitation conditions at Scutari but her achievements paled next to Barry’s, some 30 years earlier, in Cape Town. The Empire ignored his feat but continued to glorify its beloved “Lady with the Lamp”– this realization may have inspired Barry’s snit but the spat forever diminished his reputation. He was denied the knighthood his career merited, his army transgressions were revisited and Nightingale assured his omission from her Royal Commission on Army Doctors. Her legacy was as a National Treasure, his legacy was as a “footnote in Imperial Oddities.”

In his play “Whistling Psyche,” Sebastian Barry imagines the two combatants sharing a room in the afterlife. The doctor despairs of a life lived in ambiguity, “I am that other sort of creature, neither white nor black, nor brown nor even green, but the strange original that is an Irish person.” Florence has her say too, describing Barry as “a dwarf… shriveled and shrunken in his rather gorgeous uniform.” Even Psyche the poodle isn’t spared, “a little black dog with hair seemingly growing out of its very eyeballs…”

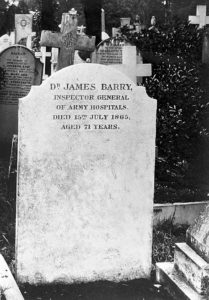

In a pointed and final gesture, the army posted Barry in Canada, a cruel destination for one of advanced age who had spent years in the tropics; he became ill and was forced him into retirement. Barry returned to London where he died in 1865 of dysentery, a disease he spent his career fighting in the colonies. He left strict orders that he be buried in the clothes he was wearing, a dictate that was ignored. When the nurse undressed him, the secret was out: Dr. James Barry “had the body of a woman, a perfect female” including stretch marks from childbirth.

Speculation on the stretch marks still continues. Was the pregnancy the result of a rape Margaret Anne endured as a girl? Or was the baby the love child of Barry and Somerset? His deathbed sex secret scandalized the Victorian establishment, Nightingale gloated, Dickens had an opinion, the army put only a sandstone marker on his grave and closed off access to his papers for 100 years.

Today, feminists see Dr. James Barry as an icon for women while the LGBTQ communities believe the doctor is a true trans hero. If you take the “he’s a she” argument, Barry would be the first woman doctor in Britain (50 years before the other “first women doctor,” Elizabeth Garrett), first woman to rise to the rank of general in the British Army and the first woman to perform a successful Caesarean section. Those who take the opposite side, “she’s a he,” reject gender binaries. They assert that for 56 years, Barry presented as a man, identified as a man and only used masculine pronouns when writing or talking about himself. After he transformed or transitioned at age 14, he never wanted his secret revealed – only Psyche saw him in the nude.

It’s a gender bender but really, what difference does it make? James Barry was fearless, a brilliant doctor and public health reformer sympathetic to patients on the margins of society. When Major McKibben, the doctor who signed the death certificate, was pressed to identify the sex of Dr. James Barry, he snapped, “None of your business!” ♦

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co- writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

As the author of the book “Well Lived” I really enjoyed this article about Dr Barry. She did what she thought was right in spite of all the obstacles put in her way . Thank you again for sharing. Best Marty Holleran

Hi! When I first saw this article, I was upset that you categorized Dr. Barry as a woman, but reading into the article further, I wanted to say that I appreciate that you respected his pronouns.

If I had to, I would probably compare all of that I read to Ignác Semmelweis’ life documentary, because the things he achieved were just as amazing, if not more amazing, and they worked in similar fields.

He was incredible, and I can’t believe that he was able to pull it off, nowadays help and transition is way more easily available for trans people, but that someone went through that in the past, and was succesful, I have no words.

He’s truly a trans icon for all trans peeps out there.

One of the images used in this article is not of James Barry, but of South African businessman Joseph Barry (https://rivertonstud.co.za/heritage/). This seems to be an oft repeated mistake on the internet. Perhaps the editors could go some way towards correcting this misconception by removing the image?