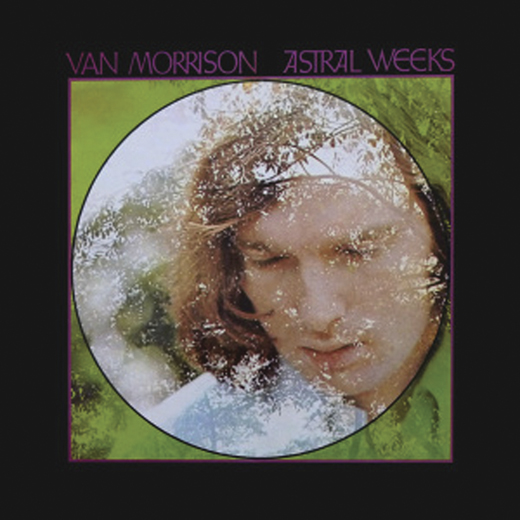

The birth, re-birth, and enduring legacy of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks.

℘℘℘

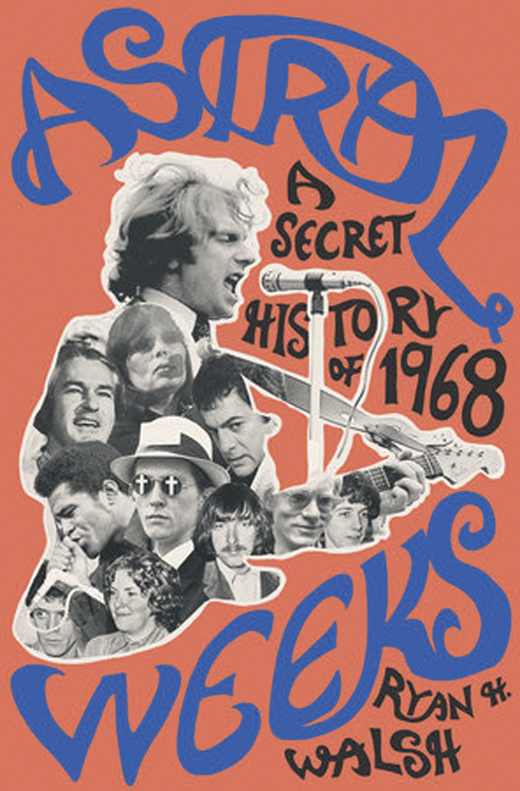

In 1968, Van Morrison was on the lam from the mob and hiding in Boston. Author Ryan Walsh takes Van’s frantic story of “another time, another place” and folds it into the radical zeitgeist of Boston Cambridge in Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968. Walsh argues that Boston, usually associated with prudery, academia, and beans, had, in 1968, just as much sex, drugs and Rock n’ Roll as anywhere else during that fevered year. The book goes on tangents, both amusing and scary, featuring Timothy Leary, Mel Lyman’s commune, the Boston Strangler, astral projection, Viet Nam, Harvard, Ram Das, a bank robbery and LSD all over the place. And, there’s something else: Boston was the birthplace of a record, ignored when released, but now considered one of the greatest in music, always on the list of All Time Top 10 Record Albums, the “sacred text of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” “the mystical document,” Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks.

Van, a singer/songwriter from East Belfast and his band, Them, attracted the attention of Bang Records in New York where Van, barely out of his teens, recorded his songs, “Brown-Eyed Girl” and “Gloria,” two hits that set of the phenomena of Celtic Rock and garage bands. When he signed with Bang Records he obsessed about having his “vision” realized but barely looked over his unfair contract. As a result, he was never paid royalties for “Brown-Eyed Girl,” a song still a staple on supermarket playlists, the omission still galling the skinflintish singer.

He battled with his producer and Bang co-founder Bert Berns. After the two had a vicious phone call, Bert dropped dead, the widow blamed Van and she made sure his contract fell into the hands of the equally hot-headed Carmine “Wassel” De Noia. “Wassel,” a mobster not inclined to take any guff from an East Belfast corner boy, made his point early in the relationship by smashing a guitar over the singer’s head. Even Van got the message and as his immigration status was as precarious as his career and life, married his American girlfriend Janet Planet (neé Risbee), and bolted to Boston. He was 23-years-old and totally broke.

In Boston, the couple laid low, starving. Soon Van emerged to perform in sleazy clubs, roller rinks and high school gyms and after some scattershot soliciting, put together a band, the Van Morrison Controversy. John Payne, Harvard student and flute player, was recruited on a wharf and later that night found himself sitting in with the band. Only when the Controversy broke into “Brown Eyed Girl,” a song Payne loved listening to on the juke box, did he realize that he was playing with the artist who wrote and sang it. As the Van Morrison Controversy became one of the hottest acts in town, Van kept writing the songs that would be Astral Weeks. The melodies and lyrics came to him in his dream as did the dictate to lay off the electric and make the album acoustic.

When word of Van and his success in Boston reached Warner Brothers, they sent producer Lewis Merenstein to check out his new material. Merenstein showed up at a rehearsal space expecting a raucous electric jam with songs akin to “Brown Eyed Girl” or “Gloria.” Instead Van showed up alone, carrying an acoustic guitar and proceeded to sing the album’s title track, “Astral Weeks.”

If I ventured in the slipstream

Between the viaducts of your dream

Where immobile steel rims crack

And the ditch in the back roads stop

Could you find me?

It took only moments for Merenstein to break down, “He vibrated in my soul…I got the distinct feeling he was going back in time to be born again.” He said to Van, “Let’s make a record.”

Sometime soon afterwards, somewhere on New York’s 9th Avenue, someone with $20,000 in a paper bag paid off the mob and Van got his Warner’s deal. But the label demanded he record Astral Weeks with New York studio musicians. But Van, usually not given to sentiment or spurts of conscience, felt loyal to his Boston guys. Perhaps that explains why he confined himself to the vocal booth, snubbing musicians, most of whom had played with legends of jazz. Van didn’t introduce himself to the players or provide them with charts, he only played the tunes on his guitar and instructed, “Follow me and don’t get in the way.”

Richard Davies, the genius of double bass picked up the groove from Van’s acoustic guitar track and after only three sessions, it was a wrap. What emerged was a new sound, a fusion of jazz, blues, soul and folk, seemingly born in a pastoral dream. It was a victory of poetry over electronics, a “song cycle” with no beginning or end, explained by Van as “mythical musings channeled from my imagination.”

The big question is: How was a vulgar, contentious alcoholic able to create Astral Weeks, a work steeped in spirituality? Was Van truly a “dweller on the threshold,” a receptacle of visions and voices, tuned into the music of the spheres? He said that, even as a child, he could leave his body and as an adult he immersed himself in the esoteric. Was he like his countryman, W.B. Yeats, another poet of Celtic mysticism?

When Astral Weeks was released, Warner Brothers, not hearing about any Glorias or brown-eyed girls, refused to promote it and the album fell into obscurity. Van became a star with his next album, Moondance (1968), and went on to be Van the Man, one of the hardest working men in show business, firing agents, managers and producers along the way. His output, not including performances, was prodigious – 39 studio albums, 6 live albums and 71 singles. He and Janet Planet divorced in 1973 and in 2000 he married (and recently divorced) a former Miss Ireland. He’s in every Hall of Fame, received every music award and, by way of being a citizen of Northern Ireland, is now Sir George Ivan Morrison. And, Mirabile Dictu!, Van has gone on the natch, even forbidding alcohol being served at any of his gigs.

Just as the theme of Astral Weeks is rebirth, the album, too, was reborn. In the 50 years following its flop, it’s taken on a life of its own, appearing in all-time best album polls worldwide and in 2015, was back on the charts. Bruce Springsteen, the Counting Crows, Ed Sheehan, Elton John all cite it as an influence and inspiration.

On the 50th anniversary of Astral Weeks, critic Jeff Melnick wrote:

“If rock has a canon, Van Morrison’s 1968 LP Astral Weeks contributes its gnostic gospels…a journey into the mystic that has scores of devoted fans, but virtually no artistic heirs. Two generations of rock critics and fans have enshrined Astral Weeks as a sui generis work of wonder and borderline madness.”

℘℘℘

W.B. Yeats, like Van Morrison was a student of Irish mythology, folklore and the occult who mined his unconscious to create art. Yeats, born 80 years earlier, was the elegant force behind Ireland’s 20th century literary revival, a senator, and the first Irishman to receive the Nobel Prize. Van, a stubby fireplug in a porkpie hat, usually with a snootful, would stop a performance to get into a fistfight with a club manager over money. Or, just because he felt like it, would finish his set by lying on the floor hanging on to his microphone. In short, he was, as Yeats would put it, “A drunken, vainglorious lout.” Yeats, with the help of his wife, the medium Georgia Hyde-Lees, engaged in automatic writing, the process of writing while channeling the supernatural, spirits from another world including dead ancestors. It was during this period that Yeats, arguably, created his greatest works. Van Morrison, too, credits automatic script to the creation of his work. What else could explain the transcendence and sense of the divine that permeates Astral Weeks? Even the singer doesn’t know as he admitted to Rolling Stone, “There are times when I’m mystified. I look at some of the stuff that comes out, y’know. And like, there it is and it feels right, but I can’t say for sure what it means.” ♦

_______________

Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 By Ryan Walsh Penguin Press, 2018

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co- writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

Leave a Reply