“The Irish-American Florence Nightingale” of the Civil War – Sister Mary Anthony.

The name of this Civil War medical pioneer has unjustly slipped between history’s proverbial cracks. Still, her legacy flourishes: “Her innovative triage techniques remain standard practices in every theater of war where American troops fight.” Those words come from a 2003 Pentagon report. They laud Sister Mary Anthony, “the Irish-American Florence Nightingale,” the woman whose innovations saved untold numbers of lives on the battlefields of the Civil War.

Her mission first unfolded amid the carnage of Shiloh, where her kind, consoling features proved the final earthly sight of many Yankees and Rebels. The middle-aged woman clad in the habit of the Sisters of Charity covered virtually every inch of the bloody turf, from the Hornet’s Nest to the banks of the Tennessee River, comforting the wounded, praying over the dead and dying, and directing stretcher bearers’ evacuation of the wounded to Union ships.

Sister Anthony, Mary (Murphy) O’Connell, had come a long way from her native Limerick and from the Ursuline Female Academy of Boston. Poverty, the arduous passage across the Atlantic and the prejudice of Boston Brahmins and Yankee workmen had not crushed Mary O’Connell’s spirit. Instead, her character and resolve “were like forged iron.”

Mary O’Connell was born in County Limerick on August 15, 1814, the daughter of William and Catherine (Murphy) O’Connell. Tragedy arrived early in Mary’s life with the death of her mother when the girl was twelve. In 1817, the “forgotten famine,” a harbinger of the Great Famine of the 1840s, engulfed Ireland and sent rising numbers of the Irish to America. Among the “ragged refuse” who trudged aboard leaky, ancient merchant ships were the O’Connells.

The exact date of the O’Connells’ immigration to Boston is unknown, but the fact that Mary received her education at Charlestown’s prestigious Ursuline Academy, where the nuns taught girls age six to eighteen years, indicates that the family set foot among “the icicles of Yankee land” sometime in the 1820s. Immigrant Irish families of the day lived mainly in the city’s North End, numbering about seven thousand by 1830 and beleaguered by Yankee mobs, who periodically vandalized Irish neighborhoods on Broad, Pond, Merrimac, and Ann Streets.

Many Irish girls of Mary O’Connell’s age worked as maids in Boston’s hotels and brownstone mansions, in many cases enduring the harsh epithets and whims of Brahmin families or in other, rarer instances becoming valued members of households. Mary was luckier in many respects than her peers, for she was accepted as a student at the Ursuline school, where she boarded with forty or so other girls. Only a handful, however, were Irish Catholics. Most of the young ladies were Protestants, boasting such Yankee pedigrees as Parkman, Endicott, and Adams. Because of the outstanding education offered by the Ursulines, a handful of Brahmin families laid aside anti-Catholic prejudice and packed off their pampered daughters to the graceful, three-story brick academy and to the ministrations of the nuns.

In August 1834, when a mob of Yankee workmen ransacked and torched the convent in a spasm of anti-Catholic rage, Mary O’Connell was twenty and had already graduated. The influence of her Ursuline mentors had ignited a vocation in her, but unlike her teachers, she did not yearn to educate daughters of privilege. She wanted to minister to the poor and the sick, and in June 1835 she was accepted into the convent of the American Sisters of Charity Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Leaving behind the familiar streets of the Irish North End, she could never shake images of the charred remnants of the Ursuline convent, testimony to the cultural and social obstacles confronting all Irish–Catholic immigrants and particularly their clerics and nuns. Mary O’Connell embraced both her challenges and her faith. She took her final vows in early 1837, and in March of that year, was assigned to Cincinnati’s St. Peter’s Orphanage.

As Sister Mary Anthony, she worked tirelessly with the city’s poor children, combining kindness with an intellect both keen and pragmatic, and rose steadily in her order’s hierarchy. By 1852, she was appointed procuratrix of Cincinnati’s St. John’s Hotel for Invalids. Nursing the sick had evolved into her true mission, and her medical skills would soon prove critical in a catastrophe about to engulf the entire nation. On April 12, 1861, the roar of Confederate cannon pounding Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, heralded the foremost challenge of Sister Anthony’s career.

Shortly after war was declared, Sister Anthony and several of her fellow nuns began to tend to Union troops ravaged by a measles outbreak at Camp Dennison, near Cincinnati. Her compassion and her knowledge of the latest nursing techniques earned her the plaudits of the camp’s officers and the attention of the Union’s chief medical body, the U.S. Sanitary Commission. Like Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix, Sister Anthony was about to reform traditional, often harmful methods of treating wounded soldiers.

The first flash of the Irishwoman’s evolving impact upon military medicine materialized during General Ulysses S. Grant’s victorious assault upon Fort Donelson in early 1862. For surgical staffs, the campaign, fought along Kentucky’s Cumberland River, posed a formidable problem in the transport of wounded soldiers from battlefields to “floating hospital ships.” From the gunwales of Union riverboats and on the battlefield, Sister Anthony devised techniques in which medical teams and stretcher–bearers sent the most severely wounded to the ships first, dispensing with the traditional practice of carting off the injured at random. Her methods, the first recognizably modern triage techniques in war zones, saved countless lives through faster hospital treatment and won her praise from President Abraham Lincoln. In tandem with her innovations in transport and treatment, she formulated fast and effective nursing programs for female hospital volunteers.

In early April 1862, Sister Mary Anthony boarded a hospital ship chartered by the Sanitary Commission and packed with other nurses and physicians, including George Curtis Blackman, one of America’s foremost surgeons. He had personally selected Sister Anthony as his chief assistant. Their destination was a Tennessee River site called Shiloh, where one of the bloodiest battles in America’s annals was raging.

Nearly 23,000 Union and Confederate soldiers littered the muddy battlefield by April 17, 1862, their moans and shrieks pealing above the riverbank. Sister Anthony moved swiftly through the carnage and oversaw the transport of casualties to the waiting ships. As always, she made no distinction between Federal or Rebel soldiers; she saw only the extent of the wound. Once she returned to the “floating hospital,” she took her place as Dr. Blackman’s “right arm” at the surgical table, mixing her practical skills with moral support for men torn apart by musket balls, grape shot, and bayonets.

At Shiloh, Sister Anthony not only proved an “angel of the battlefield,” but also cemented her burgeoning status as a luminary in wartime medicine. She used her clout to compel the Catholic Church to train rising numbers of nuns as nurses, winning the admiration of even anti-Catholic Americans.

The Catholic Church officially assigned Sister Anthony to the U.S. Army of the Cumberland on September 1, 1862, at the request of the Sanitary Commission. She ran the nursing teams at Base Hospital 14 at Nashville and comforted not only battered troops, but also runaway slaves suffering from smallpox. Sister Anthony’s efforts on the battlefield and in the floating hospitals and the surgical tents alike led the government to commemorate her service and that of her fellow Sisters of Charity.

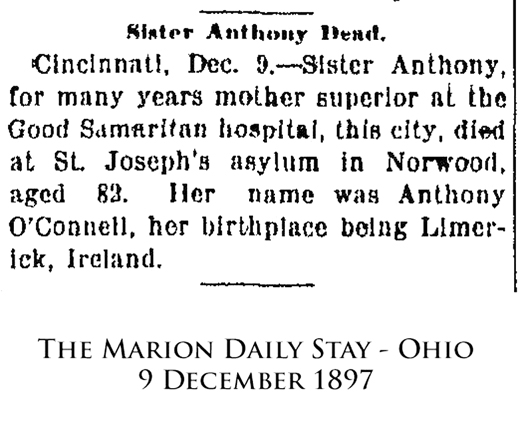

After the Civil War, Sister Mary Anthony continued her life of good works. She died of natural causes in Cincinnati at the age of 87. Her funeral, in December 1897, filled the city’s cathedral with mourners, and outside, another throng gathered to honor the gentle Sister of Charity. Whenever asked where she had come from, she had invariably replied, “Ireland–by way of Boston.”

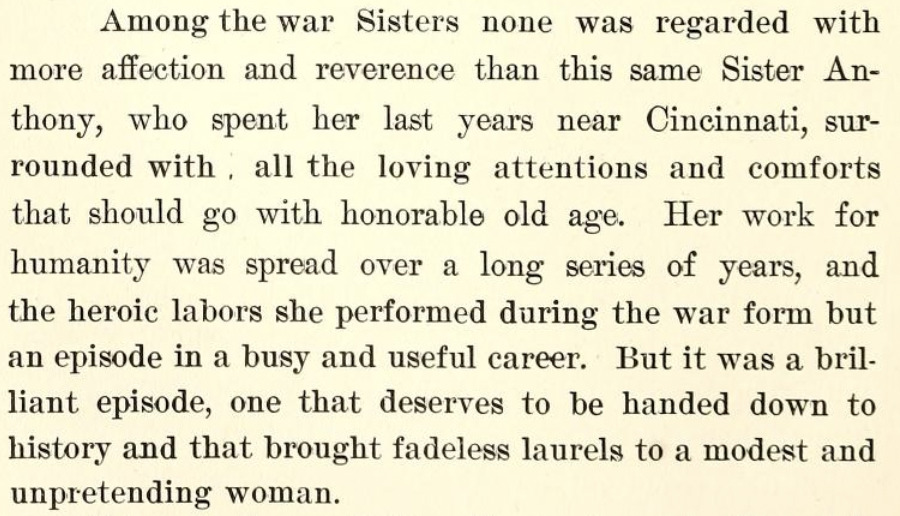

Although the names of Barton and Dix would eclipse that of Sister Anthony, the Irish immigrant, in a career of quiet brilliance, had proven her mettle second to none. In famine-wracked Limerick, in the anti-Irish streets of Boston, in the classrooms of Charlestown’s ill-fated Ursuline convent, and on the battlefields of the Civil War, Mary O’Connell’s transformation from an impoverished immigrant girl to the “Irish-American Florence Nightingale” had unfolded with dignity, compassion and sheer selflessness. Today, a portrait of Sister Mary Anthony hangs in the Smithsonian. ♦

I was privileged to work for the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati from 1993-2001. Their history is fascinating and they had (and still do) women who are outstanding across the board:

We Irish in Leavenworth, KS, are privileged to be served by the Sisters of Charity, who arrived in 1858 with some of our first settlers. They founded hospitals and the Saint Mary’s Academy, which has grown into the present University of Saint Mary.

We Hammells/Hammills immigrated from County Louth to the US in 1835. My great-grandfather served as a Union infantry soldier in the Civil War. He then married Mary Maria Barton, a cousin of Clarissa Howe (“Clara”) Barton, the “Angel of the Battlefield” and founder of the American Red Cross.

Read the book Nuns of the battlefield by Ellen Jolly Ryan and visit the monument in DC. The Ladies Auxillary of the Ancient Order of Hibernians paid and fought to have the monument erected.