Sinéad rose to fame in the late 1980s with her debut album The Lion and the Cobra. She will release a new album under a new name, Magda Davitt, in 2019. In between she has battled mental illness and controversy – she was one of the first to speak out about the abuses by the Catholic Church – but hers remains one of the purest voices in music.

Whenever her name comes up these days, a momentary panic sets in: she must be dead, she must have committed the suicide she’s been threatening for years. Relief comes with the realization Sinéad O’Connor is still alive. Alive, but in pain so palpable it seems to echo the suffering of the Sacred Heart tattooed across her chest. The Sinéad O’Connor deathwatch then resumes.

She flew too close to the sun until she flamed out in a most public and notorious way, especially as her downward spiral collided with social media. Her 2017 Facebook rant posted from a $75-a-night Travelodge in the “arse-end of New Jersey” showed a woman who bore little resemblance to the waifish vision of 1992. The singer who “didn’t want to be pretty” has finally gotten her wish – her beauty is destroyed. But even as the now-bloated tattooed matron cries into her iPad about her suicide attempts, divorces, lost children, and mental illness, the fire and fury that made her a transcendent artist are still there.

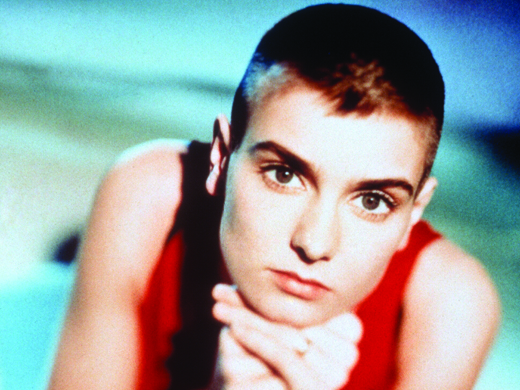

When Sinéad O’Connor first came on the scene in 1987, bald women were objects of pity (and often revulsion), assumed to be tragic victims of cancer or some other horrid disease. Sinéad, in a business where everyone does their best to look their best, was the first singer to perform with a shaved head because she didn’t want to be defined by her looks. Her rebellion backfired. Sinéad’s outré look set off an eerie loveliness and complemented her voice, a perfect instrument – both powerful and hypnotic that could range from a whisper to a frightening roar, a “banshee howl.” A gifted songwriter, song interpreter, producer, guitarist, and bassist, she could even act, once doing a turn as the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Born in 1966, in Dublin, her family was musical and creative but tumultuous, especially after the parents separated. The father, knowing the mother to be unstable, alcoholic, and addicted to drugs, tried to get custody of the five children but failed. Life became a nightmare for the O’Connor kids who suffered under a mother daily assaulting them with brooms and hockey sticks while spewing curses. The eldest child, Joseph O’Connor, an award-winning novelist and Ireland’s Literary Ambassador, confirmed their mother, who died in a car crash in 1985, was indeed violent, but defended the father. Joseph insisted Sinéad has always had the support of her siblings and asks privacy for the O’Connor family, something impossible given his sister’s compulsion to broadcast everything, private or not.

By the age of 14 Sinéad was a truant, troublemaker, and deft shoplifter, a skill she learned from her mother who would “go to hospitals and nick the crucifixes off the wall.” After running afoul of the Gardai too many times, Social Services sent her to a Magdalene Asylum run by the local church. Although charged with washing priests’ underpants, the stint put her in contact with a nun who changed her life – for the better. So moved by her singing, the nun bought Sinéad her first guitar, an instrument she learned instinctively. Once released, the teen landed a gig delivering Kiss-o-Grams, then began busking on the streets of Dublin looking to join a band.

After forming a group, Ton Ton Macoute, she secured a record contract and a manager; by the time she was 20, Sinéad was a new mother writing songs with U2’s The Edge. The following year her first album, one that she produced alone, The Lion and the Cobra, was released. Record executives took her to lunch to mandate a new image: she needed to “sex up,” wear tight jeans, short skirts, high-heeled boots and let her mid-length hair grow long. The defiant singer saw it as an attempt to “make me look like their mistresses.” Midway through lunch, without saying a word, she walked out and went straight to the local barbershop, demanding her head be shaved. The barber complied, crying the entire time.

1987’s The Lion and the Cobra introduced Sinéad O’Connor, an indie singer before there was indie rock; the record got lot of play on alternative stations and college campuses. She followed with 1990’s I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, a breakout hit, selling five million records, winning three MTV video awards, four Grammy nominations and sweeping the Rolling Stone Readers and Critics Polls. She was an instant icon, an artist described by Rolling Stone as “a mystic, writing songs about desire, God, history, loss, revolt, damnation, and independence, all with equal passion.”

On I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got she mastered musical genres from hip hop to Irish folk to punk and it was a song from this album, Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” (one that Prince had not yet recorded) that rose to the top of the charts and stayed there. The emotion she delivered in the song and the one perfect tear she shed in the video made her an international star. She was 21 and had the #1 song in the world.

Immediately after this success, the icon turned into an iconoclast who spouted abrasive and uninformed opinions, making enemies along the way. Her first career-busting move was refusing to accept her Grammy award for “Nothing Compares 2 U,” a statement against “materialism in the music industry.” Gangsta rappers NWA, the “World’s Most Dangerous Group,” joined her boycott and she, in turn, wore their logo on her shaved head. She outraged Frank Sinatra by refusing to sing the U.S. National Anthem at a concert, withdrew from her first Saturday Night Live appearance since misogynist Andrew Dice Clay was host, got into a fist fight with Prince because he objected to her language. She even made Mr. Blackwell’s worst-dressed list.

It was her second appearance on SNL in 1992 that gave her the notoriety that shot around the world, a performance that will undoubtedly be the first line in her obituary. After singing Bob Marley’s “War,” she protested the sexual and physical abuse of children by clergymen and shredded a picture of Pope John Paul II, shouting, “Fight the real enemy.” The audience froze, unable to clap or boo. Another O’Connor, the Archbishop of New York, was horrified, seeing voodoo and Satan behind the gesture, NBC banned her for life, and Madonna, an unlikely figure of righteous fury, announced she was shocked, shocked by Sinéad’s behavior. It should be mentioned that Madonna had recently posed naked, saving some elaborate bondage gear, to promote her new album Erotica and book Sex. A pop-up anti-Sinéad movement declared the USA a “Sinéad-O’Connor-free zone.”

Today, what’s notable about this act of career suicide was how prophetic she was, the first celebrity to openly denounce pedophilia in the Catholic Church. When the floodgates finally opened, stories of the sexual abuse of children by priests were everywhere and billions paid to survivors. Years later, Sinéad said that night was “her proudest night ever, an artistic gesture made by an Irish female Catholic survivor of child abuse.”

Not long after the SNL incident, she was a guest at a Madison Square Garden concert honoring Bob Dylan and his 30 years of protest music. Kris Kristofferson introduced Sinéad, saying, “Her name has become synonymous with courage and integrity,” but ironically, the audience of aging protestors and hippies booed her off the stage. Kristofferson went to hug her, “Don’t let the bastards get you down.” Her response was instant, “I’m not down.” And she wasn’t. She had, as Joan Baez put it, “the courage to screw up.”

After spending nine years dividing her time between London and Los Angeles, Sinéad returned to Dublin in 1992 to be with her son, Jake. But as her mental illness took on a life of its own, her personal life proved as shambolic as her professional. There were three more children, three more failed marriages, albums that performed poorly, and multiple suicide attempts. At different intervals she would announce a bipolar diagnosis (later redacted), PTSD, ADHD, homosexuality (later redacted), fibromyalgia, kidney stones, and had a devastating hysterectomy. It was getting exhausting reading about her and uncomfortable just looking at her. She continued to rail against the Catholic Church and the control it had over her country but, seemingly overnight, she forgave her childhood religion. In 1999, affirming her belief in the Holy Spirit, she became a Roman Catholic priest, ordained by Bishop Michael Cox, leader of the dissident Catholic Latin Tridentine Church. Her name was now Mother Bernadette Maria and she climbed up the church’s tiny ranks to become an Archdeacon. But she left the priesthood after declaring herself a Rasta. This, as it turned out, was a bad fit: Rastafarianism demand members let their hair grow long forever, no baldies need apply. They ban tattoos too, so even the large Lion of Judah on her arm was forbidden.

As Sinéad kept spinning, the tabloids kept feasting. She began sporting a grey crewcut, branded the letters “B” and “Q” on her face, and had the effrontery to get fat. Her lawsuits were legion,as were open feuds with ex-husbands, ex-boyfriends, and ex-managers. She managed to resurrect Arsenio Hall, claiming he fed drugs to Prince. She sparred with Miley Cyrus, accusing the singer of debasing her music with overt sexuality. She immersed herself in social media, not a good move for one so disturbed and so devoid of filters. She announced on Twitter, Facebook, and her website that she was looking for a “sweet sex-starved man,” who, among the specs, had to be employed, hairy and not named Nigel. One tweet brought forth Husband #4, Barry Herridge, a Vegas marriage, divorce after 16 days, and another breakdown.

The ongoing Sinéad spectacle eclipsed the memory of her genius until 2014 and a successful album, I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss, with great songs and Sinéad’s new and, yes, sexy look. One song about her flirtation with suicide, “Eight Good Reasons,” has these painful and autographical lyrics,

You know I’m not from this place

I’m from a different time, different space

And it’s real uncomfortable

To be stuck somewhere you don’t belong.

The comeback didn’t last. A series of surgeries, including one in California when her liver was accidently sliced, left her in continual pain. Suicidal and very alone, she somehow arrived at the New Jersey Travelodge, iPad in hand, to post the infamous video on August 8, 2017. It’s heartbreaking to watch, as tearful Sinéad admits, “My entire life revolves around just not dying and that’s not living.” The video went viral and overnight, she became a symbol for the many millions who suffer from mental illness, “the most vulnerable people on Earth,” deserted by society and family. Her cry, “You’ve got to take care of us…we’re not like everyone else,” inspired fans and fellow artists to offer her love and support.

She was heard, too, by America’s avuncular shrink, Dr. Phil McGraw, who put her on his talk show in September 2017. On Dr. Phil she blamed much of her sickness on her mother who ran a “torture chamber” at home, refused to wash, and “smelled of evil.” Dr. Phil sent her to his rehab, a hospital she first raved about but, after 23 days, ranted against (“lax suicide watch”), both reviews landing, of course, on Facebook.

What’s important to note about her psychotic episodes is that they weren’t fueled by drink (“I’m allergic to alcohol”), or drugs. Whether she was “born that way” – inheritor of her mother’s insanity – or irrevocably damaged by her mother’s abuse, is almost irrelevant. She is a great artist, a profound spirit, whose survival seems doubtful. Stephen Spender’s lines in “The Truly Great” seem to be written about her,

Born of the sun,

they travelled a short while toward the sun

And left the vivid air signed with their honour.

By way of a new start, she changed her name, “Sinéad is dead…free of the patriarchal slave names. Free of the parental curses.” Her new name, Magda Davitt, is heavy with biblical references. Magda is the German form of Magdalene and Davitt derived from the Irish Gaelic “meaning son of David.” This is the name she will use to tour, the name she will use to advocate for the mentally ill, the name she will use to destigmatize the disease. Let’s hope this crusade will be her legacy, not her decades of bizarre behavior. Let’s hope Magda Davitt finds the peace Sinéad O’Connor could not. ♦

….and even with all of that her spirit still is papable and when she writes and performs her own songs, they mean something…her legacy will not die because of her health problems.

I said to my twin sister when we were three

“All your life’s pain, I wish upon me”

Sinead O’Connor did this for humanity.

A beautiful moss covered root of the strongest tree.

So much pain, no real diagnoses! what do we do? what do we do!