The impact Irish creators and their characters had on the funny, and not-so funny, papers is examined

℘℘℘

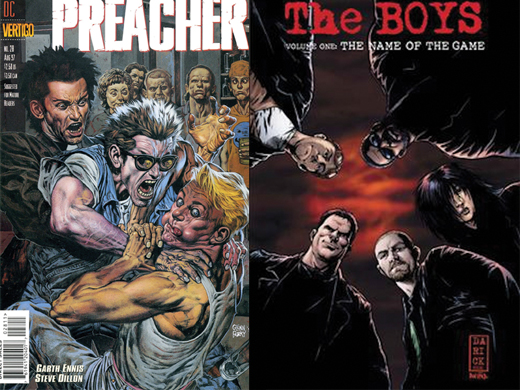

Later this year, Hollywood funnyman Seth Rogen (This is 40, Knocked Up) and his regular collaborator, Evan Goldberg, will begin overseeing production of a new Amazon series called The Boys, a kind of next-generation comic-book drama set in a world where superheroes have become so famous they have actually started to abuse their powers.

The Boys is based on a comic book series written by County Down-born Garth Ennis, who is also the creative force behind the comic book series Preacher, which has been turned into a celebrated AMC series with the same title, starring Dominic Cooper and Ireland-raised, Academy Award nominee, Ruth Negga.

Ennis has been a successful comics writer for decades, beginning with his late-1980s Northern Ireland series Troubled Souls, a collaboration with Belfast-born artist John McRea.

Ennis and McRea are merely the latest in a long line of Irish and Irish American artists who have left an indelible mark on the comic book industry, which, in many ways, has revolutionized the 21st-century world of entertainment.

Stretching back to the urchins who yukked it up on the first Sunday funny pages, through radio programs inspired by comic books, right up to longer, darker works like Preacher and The Road to Perdition, Irish comic characters and creators have played a central role in this massively popular art form.

It was a non-Irishman, however, who created one of the most popular “Irish Kid” comic characters of all time. Richard Felton Outcault was born in 1863 in Lancaster, Ohio, far from the crowded New York slums that housed Irish Famine immigrants and their children. Yet Outcault, who moved to New York in 1890, would go on to become a newspaper artist and – for better or worse – create one of the most influential images of the Irish in America, reflecting both the negative stereotypes and harsh realities of immigrant life.

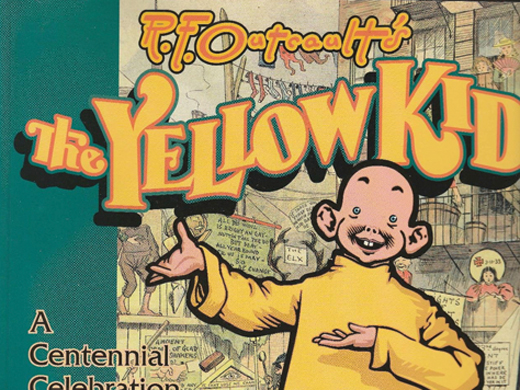

In the mid-1890s he created the comic figure Mickey Dugan, known to millions simply as “The Yellow Kid.” Dugan lived in a fictional place called Hogan’s Alley. But his real home was the wildly popular Sunday newspaper comics pages which were first introduced in the 1890s. Clad in a yellow pajama shirt, bald so that he could fend off pervasive lice, Mickey Dugan is the source of the infamous term “yellow journalism,” and changed the media landscape forever. Outcault is credited with not only creating memorable characters, but also popularizing key staples of the comics form, including using word balloons for dialogue.

“The Yellow Kid” was not an individual but a type,” Outcault once said. “When I used to go about the slums on newspaper assignments I would encounter him often, wandering out of doorways or sitting down on dirty doorsteps. I always loved the Kid. He had a sweet character and a sunny disposition, and was generous to a fault. Malice, envy, or selfishness were not traits of his, and he never lost his temper.”

(The reality of Irish youth on the streets was a lot more harsh. Famous social reformer Jacob Riis once noted that nearly one of every five people charged with unlawful begging in New York in 1889 were Irish.)

The first full-color Yellow Kid comic ran in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World newspaper in February, 1895. The Kid proved so popular that in 1896, William Randolph Hearst lavished money on Outcault, convincing the artist to bring his Irish characters to the rival New York Journal-American.

Jiggs and Maggie

The Kid started a movement and soon most national newspapers had full-color comics pages, and they were bursting with all aspects of immigrant life. “By the early 20th century, a new wave of immigration had greatly increased the ethnic populations of the United States, and this demographic change was reflected in the comics,” a fact noted in the book Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas.

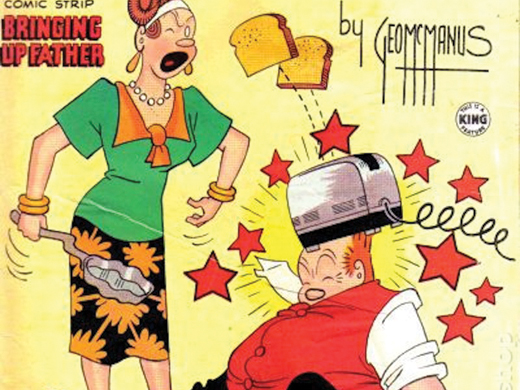

Among the most popular was The Katzenjammer Kids, a strip which reflected German-American life. But there was also the Irish-American married couple Jiggs and Maggie in the comic strip Bringing Up Father, which debuted in 1913 and – astonishingly – ran in different versions with different writers and artists all the way up until 2000. Bringing Up Father was created by St. Louis-born Irish American George McManus, who found humor not only in immigrant life, but the clash of Maggie’s “lace curtain” aspirations and George’s “shanty” roots.

Jiggs and Maggie proved so popular with early 20th century audiences that they would appear on Broadway stages throughout the 1920s in shows which placed the family in Florida and even Ireland.

Bringing Up Father would later inspire a radio series, silent films, and talkies, with Hollywood veteran Agnes Moorehead in the role of Maggie. In later movies such as Jiggs and Maggie in Society and Jiggs and Maggie Out West, Jiggs was portrayed by Joe Yule, whose son, also named Joseph, would become better known by his stage name, Mickey Rooney.

Famous Irish Roots

Meanwhile, another media revolution was unleashed in 1938, when a flying hero called Superman appeared on the cover of Action Comics #1 – a copy of which sold a few years back for over $3 million.

For all of their fantasy and futuristic touches, old-world immigrants were central to the so-called “Golden Age” of comics.

As a recent Religious News Service feature put it, “the very origins of the superhero industry in the United States… was a Jewish business.” Superman was created by Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel. Stan Lee created Spider-Man, the Hulk and the Fantastic Four. Batman was the brainchild of Bob Kane, born Robert Kahn in New York City in 1915.

For the Irish there was Steve Rogers – better known as Captain America, who debuted in 1941, and is at the center of Avengers: Infinity War, the latest blockbuster from Disney’s Marvel Studios. It’s widely acknowledged that Captain America is the son of immigrants from Ireland who settled in New York’s Lower East Side.

Two decades later, 1961, another iconic Marvel character with Irish roots, Hell’s Kitchen native Matt Murdock, “a red-haired Irish Catholic …raised in poverty,” made his debut as Daredevil, as the recent book Working-Class Comic Book Heroes notes.

Ben Affleck played Daredevil in the 2003 movie and Netflix is currently in Season 3 of a Daredevil series. Meanwhile, the fabled X-Men series debuted Dublin bad boy (cousin of another character named Banshee) Black Tom Cassidy in 1976.

The Irish and other ethnicities were so central to the Golden Age of comics that in Michael Chabon’s celebrated novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay, the author made sure that three of his striving young comic creators were Irish, Italian, and Jewish kids from New York’s ethnic enclaves. Like Daredevil, one of Chabon’s aspiring artists is Davy O’Dowd, “born in Hell’s Kitchen,” having “lost part of an ear in a fight when he was 12.”

Pogo and the Prince

As for popular real-life, Irish-American artists, there was Walt Kelly (1913-1973), a Philadelphia native best known for his strip Pogo, an absurdist take on modern life featuring animals debating various issues of the day. At the height of its popularity, Pogo was widely syndicated, and ran in various forms from the 1940s to the 1990s.

Then there was the cartoonist and illustrator, John Cullen Murphy, the subject of a new book called Cartoon County: My Father and his Friends in the Golden Age of Make-Believe. Written by Murphy’s son, Cullen Murphy (an author and former editor at the Atlantic Monthly), Cartoon County is about a collection of cartoonists who all lived in one Connecticut town, but also about the eight Murphy children, and time they spent in Ireland.

John Cullen Murphy is best known for his decades of work on the popular adventure comic Prince Valiant, which he took over as illustrator from the comic’s creator Hal Foster in 1970, with his son, Cullen taking over as the writer of the series in 1979.

Just before that, Murphy’s son writes, “our family relocated to Ireland” for two years, while Murphy was also writing and drawing a boxing strip called Big Ben Bolt. A subsequent Bank of Ireland strike provided Murphy with an opportunity to both dazzle his children and put his art to more practical use.

“We had finally run out of cash,” Cullen Murphy writes. “How could we get cash? My father went to his drawing board.” John Cullen Murphy proceeds to create his own artful Bank of Ireland checks, complete with “his own fanciful version of the bank’s great seal.” Local shopkeepers never questioned Murphy’s fiscal art.

“The character Harold in Crockett Johnson’s famous children’s book uses a purple crayon to draw his own reality wherever he goes,” writes Murphy. “My father apparently possessed this same power. Every cartoonist did.”

The New Generation Even as Prince Valiant and Pogo continued running in newspapers, comics – and the entire entertainment industry – underwent a radical evolution in the late 1980s, beginning with Irish-American actor Michael Keaton’s star turn as Batman in director Tim Burton’s dark new take on Gotham’s caped crusader. Suddenly, superheroes were complicated, and comic books – and longer so-called “graphic novels” – became equally complex.

One of the most interesting of the 1990s was The Road to Perdition, about an Irish-American gangster named Michael O’Sullivan, (based loosely on the real-life criminal John Patrick Looney). In 2002, The Road to Perdition was turned into an acclaimed movie starring Tom Hanks and Paul Newman, and directed by Academy Award-winner Sam Mendes.

The Irish in comics and graphic novels have become only more prominent in the 21st century, with artists like Derek McCulloch exploring 100 years of the Irish immigrant experience in Gone to Amerikay, Christine Kinealy and John Walsh recounting the Great Hunger in The Bad Times: An Drochshaol, and Irish-born Gerry Hunt releasing an entire series of graphic novels about Irish history.

Meanwhile, a recent mini-series entitled The Brave and the Bold placed Batman and Wonder Woman in the mythical Irish land of Tír na Nóg.

As for the movies, all of Hollywood seems to revolve around comic characters these days. Having earned two billion dollars, of course, Captain America will be back next May, in the second part of the Avengers: Infinity War saga. And with studios mining every aspect of a comic character’s backstory these days, could a movie about Captain America’s Irish roots really be that far behind? ♦

Very interesting and informative article – go h-an mhaith ar fad. Ana suimiul mar gheall ar stair scriobhnoiri Eireannach/Americeanach go hairithe sna “paipeiri grinn” ins na Stait Aontaithe. Interesting fact is the Irish for USA is Stait Aontaithe Meiricea – SAM – Uncle Sam – geddit? Never mind – just thought I’d mention it.