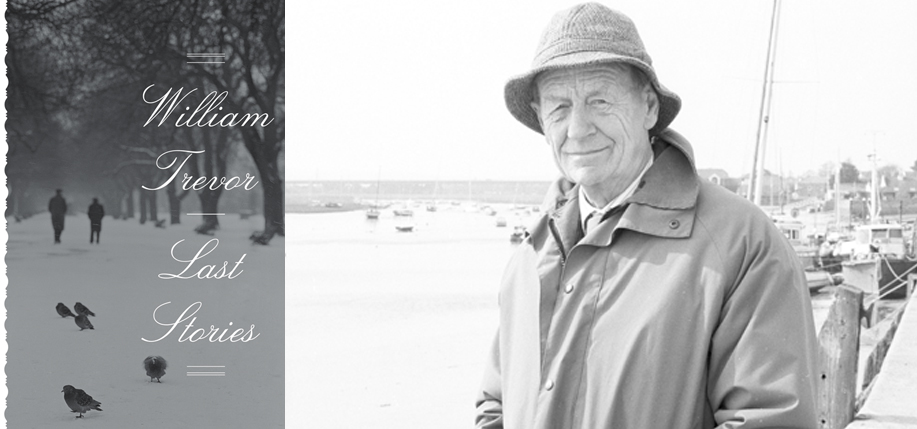

William Trevor’s posthumous Last Stories.

℘℘℘

How strange to read a published work knowing it to be the author’s last. Such was the feeling on opening Last Stories, a collection of short stories made available two years after William Trevor’s death. The Cork-born author leaves us a treasure of quality work, fronted by an impressive canon of 14 novels – the last, Love and Summer, was his fifth nomination for the Man Booker Prize and several others, including Felicia’s Journey and Fools of Fortune, were adapted for the big screen.

However well received his novels, he has always been regarded as a master of the short story. One particular classic, “The Ballroom of Romance,” evoked 1950s dance hall days in the west of Ireland and was memorably adapted for television by RTÉ in 1982.

The New Yorker once described Trevor as “the greatest living writer of short stories in the English language.” In lucidly Chekovian tales, his prose flows with a trademark simplicity that belies the craft and complexity pulsing beneath.

With 13 collections already published in his name, it is by way of fond farewell that Viking presents this unexpected treat, 10 new stories that the master was studiously crafting in the autumn of his 88 years. There are certainly moments here to justify his exalted reputation.

“The Piano Teacher’s Pupil” stands out as vintage Trevor, a succinct masterpiece with a delicious twist midway through. It embraces themes found elsewhere – personal loss, unrequited love, and the forgiveness of disappointment. Miss Elizabeth Nightingale, the eponymous teacher, once had a 16-year affair with a married man, “but since then she had borne her lover no ill will, for after all there was the memory of a happiness.”

It’s a gem. Here and elsewhere, through sympathetic characters navigating everyday challenges, he nudges the reader without supplying tidy solutions, confidently resisting the urge to wrap matters up in a bow. How recognizable his deceptively simple style, the hallmark of prose so easy to read that it prompts a misconception that it must have been equally easy to write.

Most of the stories are situated in England – only two take place in Ireland – so through its 213 pages we are taken mostly around London. In settings as English as drawing rooms and afternoon tea, Trevor offers us a glimpse of society, possibly as genteel as it once was. His characters are sensitively drawn and the preoccupations overwhelmingly middle-class. The collection beckons a bygone age dominated by social division and etiquette. Although Last Stories might be accused of overlooking, if not avoiding, modernity, its concerns are typically ordinary people and how life’s frailties afflict and disrupt everyday existence.

Little surprise then is a passing remark in “Mrs. Crasthorpe:” “How good the everyday was, the ordinary with its lesser tribulations and simple pleasures.” It may as well represent the author’s own philosophy. For such an accomplished hewer of the human condition, the quotidian is the well from which he draws most inspiration.

Equally striking is how empathetic he is to his characters and, by extension, how forgiving they are to the people who cause them grief. “At the Caffé Daria” tells a story of competing lovers, one of whom, Andrea Cavalli, is “not embittered” by his wife’s departure to the arms of a silver-tongued poet.

Curiously, the same theme is repeated in “The Women,” where Mr. Normanton loses his wife “not to the cruelty of an early death but to her preference for another man.” At 31 pages, it’s one of the longer entries, but one wonders had the story idea come to him earlier might he have developed its potential as a novella. Several shifts in the main protagonist make it a less satisfying read.

Dublin streets provide possibly the book’s grimiest backdrop in “Giotto’s Angels,” a story of survival for an amnesiac and a prostitute.

Another adulterous tale, “An Idyll in Winter,” details the plight of two women coveting an indecisive Yorkshire man. Typical of Trevor is that an injured bystander plays a key role, in this case the man’s young daughter who enters this tug-of-love as collateral damage.

Elsewhere, “The Unknown Girl” deals with the mystery of a fatal road accident in which the identity and background of the victim is attentively explored. From such promising beginnings the denouement feels almost too subtle. Known as a perfectionist for the infinite care he would take to polish each story to a shine, it is not a surprise that “Taking Mr. Ravenswood” is one of three stories not previously published. It ends with such uncharacteristic abruptness that one might reasonably wonder whether the story had been completed to its creator’s satisfaction.

Reaching the end of the collection, I recalled interviewing Trevor for Irish America several years ago. He told me that he dedicated each publication to his wife Jane Ryan. Unfortunately she pre-deceased him by two years. In a turn almost reminiscent of the great author himself, I found myself searching for her name at the front pages only to find the space blank, loving authorial words sadly missing in this welcome posthumous tribute. ♦

Last Stories is published by Viking (May 2018 / 213 pp. / $26)

_______________

Frank Shouldice is an author, playwright, and documentary maker. He has worked in journalism across print, radio, and television, where he is a producer/director with the investigations unit at RTÉ. He won the 2016 Justice Media Overall Award for his radio documentary “The Case That Never Was” and is the author of Grandpa the Sniper: The Remarkable Story of a 1916 Volunteer (Liffey, 2015), about his grandfather’s role in the 1916 Easter Rising and War of Independence.

Leave a Reply