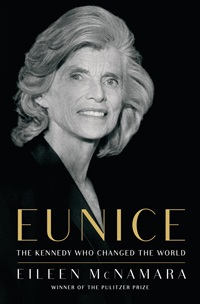

Eunice Kennedy was an amazing woman who changed the way people with disabilities are treated and viewed. Who better to bring her story to light in a new biography than Eileen McNamara, another trailblazing Irish American.

℘℘℘

Eileen McNamara – the longtime Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe columnist who now directs the journalism program at Brandeis University – grew up in Kennedy country.

“I grew up in North Cambridge, in what was then Tip O’Neill’s congressional district, the seat previously held by John F. Kennedy,” McNamara recently told Irish America via email. “It was a largely Irish, working class neighborhood.”

For the past several years, McNamara has been living with a different member of Irish America’s royal family. The result is a new, highly acclaimed biography about (as the subtitle puts it) “the Kennedy who changed the world.”

It is a provocative title because – for all the fame and accomplishments of Joe and Rose Kennedy’s nine children – McNamara is implying that only one actually changed the world.

It was not the dashing Jack, or martyred Bobby. It was the middle child – Eunice Kennedy Shriver. It was Eunice, McNamara writes “who left behind the Kennedy family’s most profound and lasting legacy.”

Eunice “advanced one of the great civil rights movements, on behalf of millions of people across the world with intellectual disabilities.”

Such a bold claim is at odds with what McNamara knew of her subject when she considered taking on this project, at the request of Priscilla Painton, vice president and executive editor at publisher Simon & Schuster.

“I knew little about [Eunice Kennedy] beyond her association with Special Olympics, but I suspected Priscilla’s instinct was correct, that this was an accomplished political actor who had been overlooked because of her gender.”

Indeed, central to McNamara’s book is the degree to which the Kennedy family – especially patriarch Joseph Sr. – lavished praise and expectations on the boys, leaving the girls to more or less fend for themselves.

As McNamara writes, Eunice Kennedy’s “struggles to be seen – on the public stage and in her own family – mirrors the experience of so many ambitious women in mid-twentieth century America who had to maneuver around the rigid gender roles that defined the era.”

Not that, as McNamara noted to Irish America, Eunice was afraid to point this out.

“Her father mistakenly assumed his Stanford-educated daughter was killing time until marriage. ‘You are advising everyone else in that house on their careers, so why not me?’ she once asked him. She knew the answer. For Joe Kennedy, power was the province of men, not women. What Joe would not give, Eunice took.”

And so, Eunice Kennedy turned a family charitable foundation named after her late brother Joe Jr. into what McNamara called “an engine of social change on behalf of those with intellectual disabilities and – in doing so – she carved a role in national politics at least as consequential as that of her more famous brothers.”

In this day and age, it might seem hard to believe that there is actually a Kennedy about whom not much is known. Yet McNamara’s is the first full-length look at Eunice Kennedy Shriver’s very full, very complicated life.

“There are hundreds of books about Joe, Jack, Bobby, and Ted,” McNamara noted. “There are dozens about Rose, the Kennedy matriarch, and Jackie, the glamorous first lady. Laurence Leamer did a book called The Kennedy Women, which included Eunice. But there were vast swaths of her life story that had never been uncovered and so had never been told.”

McNamara spent time in archives in Boston, London, Chicago, and Palo Alto, California. The first thing that surprised her about her subject was how “often [Eunice] got there first.”

McNamara said: “Eunice worked for the State Department two years before Jack arrived on Capitol Hill in 1947. She administered a task force on juvenile delinquency in the Justice Department fourteen years before Bobby tackled the issue as attorney general. She worked with women in a federal prison more than 25 years before Ted took on prison reform in the Senate.”

Of course, for all of their notoriety – indeed, because of it – the Kennedy family is famously guarded.

“It took a long time to convince the five Shriver siblings to cooperate with this biography,” McNamara said. “Their reluctance was understandable. The Kennedys have not always been dealt with honorably by historians and journalists, but once they accepted that I was not interested in writing either a hagiography or a hit job, they gave me access to their mother’s personal papers, dozens of boxes of uncatalogued material that they had never even read themselves. It was a profound act of trust.”

The children, McNamara added, “asked only that I share with them any alarming information I found in those boxes. There was none, and they made no effort to meddle with my research or my conclusions or to censor the manuscript.”

McNamara also added that Bobby Kennedy’s widow, Ethel, was “very generous with her time and her memories of her sister-in-law.”

McNamara’s own Irish roots are as strong as her subject’s.

All four of her grandparents were born in Ireland and came to Boston. Her maternal roots are in Ennistymon, County Clare, while her father’s family hails from Malin Head, County Donegal.

“My own father worked for the post office,” McNamara added. “I was first in my family to go to college, to Barnard College on a full scholarship facilitated by my Irish American English lay teacher at North Cambridge Catholic High School. She had won a scholarship to Barnard 10 years earlier through her father’s longshoremen’s union in Brooklyn and convinced Barnard that I showed some promise. My mother listened to the Irish Hour on the radio every Saturday afternoon and I took Irish step dancing lessons for years, never once winning a medal at an Irish feis, to my mother’s chagrin.”

McNamara went on to the Columbia School of Journalism, before becoming a Nieman Fellow at Harvard. She would eventually end up spending 30 years at the Boston Globe, starting out as a secretary in the newsroom and rising through the ranks to become one of the Globe’s top columnists. McNamara won the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 1997, and was a key contributor to the Globe’s dogged coverage of the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal in Boston. McNamara was even a character (portrayed by actress Maureen Keiller) in the Academy Award winning film Spotlight, about the Globe’s coverage.

During her research, McNamara came to see that the Kennedys have “a complicated relationship with their Irishness.”

She added: “Joe Kennedy balked at being called an Irishman. In his eyes, he was as American as any of the Boston WASPs who rejected him for country club memberships and a place on the board of overseers at Harvard. But Rose played Irish tunes on the piano in Hyannis Port while her father, John ‘Honey Fitz’ Fitzgerald – the colorful former mayor of Boston – sang. The children absorbed the story of Irish struggle, of fighting to claim a place in a hostile world. Joe’s children were the beneficiaries of his determination to claim the American dream for them.”

Eunice herself, McNamara said, “came back from her time in London – while Joe was U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James – with a British accent.”

And yet, she was also able to share in a very special Irish moment with her brother.

“She accompanied President Kennedy on his trip to the family’s County Wexford ancestral home in Ireland in 1963, declaring it one of the highlights of her brother’s presidency.”

Perhaps the strongest part of McNamara’s book is her even-handed analysis of Roman Catholicism’s influence on Eunice Kennedy.

“Catholicism was central to Eunice’s identity,” said McNamara. “But hers was not the reflexive Catholicism of rules and rituals and rosaries. She thought deeply about ethics, adhering to the ‘consistent ethic of life’ tradition of the Catholic church, what Cardinal Joseph Bernadin described in 1984 as the ‘seamless garment doctrine.’”

This doctrine argues that human life, “no matter how developed or how compromised, is sacred and deserving of protection,” noted McNamara. “Believing that life begins at conception, she opposed abortion just as she opposed capital punishment and euthanasia. In the 1960s, before Roe v. Wade, as states began to repeal the 19th century statutes that had criminalized abortion, she had lots of company among liberals, many of whom saw abortion as a weapon being wielded against the poor.”

McNamara added: “The politics of abortion changed after Roe, but Eunice remained consistent in her opposition. She would have been enraged by the decision of organizers of the Women’s March in 2017 to exclude opponents of abortion, believing it was not incompatible to fight for the equality of women and to oppose abortion.”

Having completed this ambitious biography, McNamara – who has three children with her sportswriter husband Peter May – is not sure what her next big project will be.

“I am not very good at predicting the future. Most of my life has been a surprise,” she said. “I am focused at the moment on grading a stack of essays from my media and public policy class.”

And even though she is no longer grinding out regular newspaper work, she also can’t completely shake the habit, contributing columns to the opinion page of WBUR, Boston’s NPR radio station.

“Once you’ve been given license to share your opinion,” McNamara said, “it’s a hard habit to turn off.” ♦

_______________

Tom Deignan writes columns about movies and history for Irish America and is a weekly columnist for the Irish Voice and regular columnist and book reviewer for the Newark Star-Ledger. Most recently, he co-wrote, with the late Tom Hayden, an essay on Thomas Addis Emmet in the new book Nine Irish Lives (Algonquin, 2018).

Leave a Reply