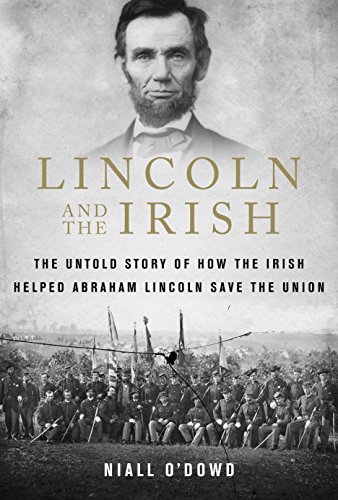

An excerpt from Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union, by Irish America publisher, Niall O’Dowd.

Mary Todd Lincoln was of solid Irish stock.

Mary’s paternal great-grandfather, David Levi Todd, was born in County Longford, Ireland, and came to America, via Pennsylvania, to Kentucky. Another great-grandfather, Andrew Porter, was also of Irish stock, the son of an Irish immigrant to New Hampshire and later Pennsylvania. Abraham Lincoln was primarily of English descent, though there was some Scots-Irish in his roots, namely a McLoughlin and a McKinley.

Mary Todd moved to Springfield, Illinois from Kentucky in 1839, at the age of 21. She went in order to escape her stepmother, live with her sister Elizabeth, and begin the search for a husband. Springfield had become the state capitol and was overrun with men fastening down political and lobbying careers, as well as a plethora of chancers, fakers, hustlers, and some do-gooders.

Women were in short supply, which suited Mary Todd. Back then, a woman’s prospects in life depended on what kind of marriage she made, not on her own abilities. Mary was determined to meet the right match.

She had “a well-rounded face, rich dark-brown hair and bluish-grey eyes,” according to Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon, who was no fan. She spoke fluent French and had a long and distinguished ancestral line. Mary was about five foot two and weighed about 130 pounds, though in later years she would gain weight.

She and Lincoln became acquainted at a cotillion. “Who is that man?” is what Mary said in reaction to seeing for the first time the long, gangly figure of the country lawyer and budding politician. Her reaction to seeing Lincoln was recorded by Mary’s niece, Katherine Helm.

Later at the cotillion, Abraham Lincoln came over and said, “Miss Todd, I want to dance with you in the worst way.” They had a stormy courtship, a presentiment of what was to come. In the fall of 1842, the couple decided to be married, despite her family’s concern about his rough-hewn background. Her sister Elizabeth, who had brought her to Springfield, had married well to Ninian Edwards, the son of a former governor, and tried to break up the match to the backwoodsman.

She wrote, “I warned Mary that she and Mr. Lincoln were not suitable. Mr. Edwards and myself believed that they were different in nature and education and raising.”

When Mary announced their wedding would go ahead, her sister exploded. Elizabeth “with an outburst, gave Mary a good scolding, saying to her vehemently ‘Do not forget you’re a Todd,’” Mary’s other sister, Frances, remembers.

Even his accent and voice were a drawback, a country bumpkin mixture of Indiana and Kentucky and a high-pitched voice at odds with his great hulking figure.

Speaking of his looks, it was bad enough her sister thought she was marrying beneath herself in the incredibly class-conscious mentality of the time, but then there was Mr. Lincoln’s visage and presentation.

When he became a national contender, Lincoln was memorably described in the Houston Telegraph as “the leanest, lankiest, most ungainly mass of legs, arms, and hatchet face ever strung upon a single frame. He has most unwarrantably abused the privilege which all politicians have of being ugly.”

In an era before photographs, such descriptions were damning. An anti-Lincoln refrain ended with the lines “Don’t for God’s sake show his picture.”

A reporter for The Amboy Times who went to hear Lincoln speak was hardly flattering about his appearance, but he found his two-hour speech mesmerizing.

“He is about six feet high, crooked-legged, stoop shouldered, spare built, and anything but handsome in the face. It is plain that nature took but little trouble in fashioning his outer man, but a gem may be encased in a rude casket.”

Lincoln realized his best bet lay in a flattering photograph, the exciting new technology. He was perfectly aware his ungainly body, oversized hands, hard-edged and lined face, and physical presence at six foot four (in an era where the average male height was five foot seven) could be off-putting. When he launched his presidential bid, he turned to Irish photographer Matthew Brady, the Annie Leibowitz of his day.

Brady claimed he was born near Lake George in upstate New York in 1822. No birth certificate or any kind of documentation has been found to link his birth to New York State. In fact, an 1855 New York census lists Brady’s place of birth as Ireland, as do an 1860 census and Brady’s own 1863 draft records. His parents, Andrew and Julia, were Irish immigrants. Given the suspicions and prejudice about Irish Catholic immigrants, Brady may have preferred to claim American birth.

He grew up in Saratoga Springs and became fascinated with the new art of photography, eventually opening his own studios in New York City. He became known as the best photographer in town at a time when the craft was in its infancy and the rich were clamoring for their likenesses to be created.

Brady had poor eyesight and hired others to take most of his photographs, but he “conceptualized images, arranged the sitters, and oversaw the production of pictures.” Plus, according to The New York Times, Brady was “not averse to certain forms of retouching”; an early Photoshop genius, in point of fact.

The photograph he took of the future president, which coincided with Lincoln’s breakthrough speech at the Cooper Union in February 1860, flattered his subject greatly. Brady bathed Lincoln’s face in light to hide the hard edges and wrinkled, sallow skin. He told him to curl up his fingers to hide the sheer length of his hands. Brady “artificially enlarged” Lincoln’s collar so his gangling neck would look more proportional.

Lincoln loved it, later saying, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.” In all, Brady and his team took thirty photographs of him. Those pictures shaped his legacy of being the first American president made truly accessible by photographs.

Whatever he looked like, Mary Todd was in love, as was her beau Abe with her. The wedding ring Lincoln bought her had an inscription that read “A.L. to Mary, Nov. 4, 1842. Love is Eternal.”

Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd were married at her older sister Elizabeth’s home on Friday evening, November 4, 1842. She wore her sister’s white satin dress and a pearl necklace. About thirty relatives and friends attended the ceremony. It rained.

In 1844, after living in lodgings in Springfield, they moved to 8th Street and Jackson, as their son Robert, who had been born the previous August, grew older. Mary loved her new home. “The little home was painted white and had green shutters. It was sweet and fresh, and Mary loved it. She was exquisitely dainty, and her house was a reflection of herself, everything in good taste and in perfect order,” a friend reported.

As the family expanded, there was a need for maids. Lincoln’s improved financial circumstances meant that help could be hired. Many at the time came straight off the boats from Ireland and Germany. Vere Foster, an agent for the Women’s Protective Emigration Society in New York, was constantly being petitioned to send young girls into service in Illinois. She eventually sent 700, most of them Irish and German.

These young women found homes in Springfield, as well as other Illinois towns. Several at various times were hired by the Lincolns.

Despite her own heritage, Mary Todd Lincoln disliked the Irish and was thought to favor the Know-Nothings, the virulently anti-Irish Catholic grouping that split her husband’s Whig party. She wrote to a friend in Kentucky, “If some of you Kentuckians had to deal with the Wild Irish as we housekeepers are sometimes called upon to do, the South would certainly elect Fillmore (who was favorable to Know-Nothings) the next time.” Lincoln, on the other hand, made clear he was not against the Irish. After all, he was surrounded by them as domestic help at home, and many historians believe the help shielded him from the worst of his wife’s tantrum excesses.

The women hired were mostly young and single. Their pay was $1.00 to $1.50 a week. (In contrast, Lincoln made up to $2,500 a year as a lawyer.) The work was exhausting—laundering, emptying chamber pots, and looking after four rambunctious boys who were poorly disciplined by their parents to begin with. Later, Mary Todd Lincoln would be called “Hellcat” as a nickname in the White House. She was just as hard on her Irish maids.

Catherine Gordon, from Ireland, was named as living in the household in the 1850 census. She was likely the one who enraged Mary Todd Lincoln by leaving her window open so boyfriends could enter. Ten years later, Mary Johnson, also from Ireland, was in situ for the census. Mary was likely the one that Abe Lincoln paid to put up with his wife’s tirades, an extra dollar a week slipped to her in order to placate and manage his wife.

Margaret Ryan, another Irish native, claimed she lived at the Lincoln household until 1860 and witnessed Mary hitting her husband and chasing him out of the house on several occasions. She stated all this in an interview with Jesse Weik, who helped William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, write his definitive biography of Lincoln. Herndon hated Mary Todd Lincoln, and as a result, the Ryan stories are hotly disputed. But there are more than enough stories told by disparate figures over her lifetime to suggest that Mary Todd Lincoln was a deeply troubled woman, a condition exacerbated by the death of three of her children.

Lincoln’s niece Harriet Chapman, who worked for a time with Mary, stated she had nothing good to say about her but could talk about her uncle all day. Unpredictable outbursts and unreasonable demands was one description of Mary Todd Lincoln’s behavior at the time.

Perhaps the most poignant moment of all is when Lincoln took her to an upstairs room in the White House after her grieving for her dead son Willie had sent her into a profound depression. “Mother,” he said quietly to her, “You see the insane asylum yonder. You will have to go there if you cannot stop the grieving.” It was a harsh choice for a woman, who had little medical expertise at the time to help treat her. It also spoke volumes for Lincoln’s desperation for her to get better.

Throughout all those trying times and despite Mary Todd’s scorn, Abraham Lincoln often focused on the story of the Irish who were flooding into America and sang the praise of their heroes. ♦

_______________

Lincoln and the Irish is published by Skyhorse Publishing (February 2018 / 224 pp. / $24.99).

Lincoln’s greatest speech was the Gettysburg address, which he made in the fall of 1863. As the famous Civil War President read this most memorable speeah, beside him on the platform stood Andrew Gregg CURTIN, the Governor of Pennsylvania. The Governor’s father was an immigrant from County Clare.

Nice job, Niall, as usual. Maids, soldiers, generals, the ancient Irish showed what they could do when given a chance. God bless President Lincoln and the USofA. I really enjoyed this – the gal leaving her window open! Abe Lincoln noted that Mary’s blowing up at him did her so much good. Now there’s a man. Good luck with sales – and don’t forget my article on President Patrick MacMahon of France I recently sent you and Patricia! More to come – Roosevelt and the Abbey Theatre….

Abraham Lincoln was the greatest politician, thinker, and raconteur America has ever produced. He is a Man for the Ages. The Civil War. cost the lives of 634,000 soldiers and twice that amount was wounded. Lincoln set the stage for freedom for all mankind. Washington made our country, Lincoln saved it! At Gettysburg, Douglas spoke for 2 hours in the hot sun. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address lasted three minutes and remained one of the greatest speeches ever.

I used to think Lincoln’s query “whether a nation so dedicated could long endure” was merely rhetorical. Now I recognize it was existential.