The Choctaw “Trail of Tears,” tribe raised money for Irish Hunger relief.

Visiting New York in 1989, Don Mullan, the then-director of Action From Ireland (AFrI), a Dublin-based human rights organization, was addressing members of the American Irish Political Education Committee about AFrI’s “Great Famine Project.”

The Project had begun in 1988 as AFrI leadership reflected on the historical neglect of Ireland’s Great Hunger, when over one million souls were consigned to unmarked mass graves. The Project was conceived to honor the memory of these forgotten souls by linking their story with that of the suffering poor throughout the world. AFrI proposed to initiate an annual ten-mile-long Great “Famine” Walk from Doolough to Louisburgh (Co. Mayo), to commemorate the 600 Irish men, women and children who perished in a 24-hour period as they traveled across the Mayo Mountains in harsh weather in a desperate search for food.

After Mullan completed his presentation at the meeting, a young man approached him and asked whether he knew that the Choctaw, a North American indigenous tribe had identified with the plight of the Irish and raised funds for hunger relief during the starvations of 1845-49.

Mullan was intrigued. Prompted by a desire to unearth evidence of the commonality of the human experience in oppression, he investigated the Choctaw-Irish link. He contacted the Oklahoma branch of the Choctaw and discovered a historical reference to the Choctaw donation to the Irish in 1847. He conducted a radio interview with the Choctaw Assistant Chief, and from that point, “the rest is history.” According to Mr. Mullan, “My contact with the Choctaw aroused a great deal of interest among the Irish and Choctaw, and as a result, a great friendship has developed.”

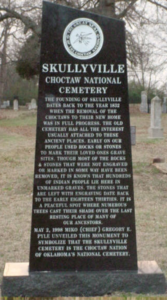

In 1990, on a trip to the U.S., Mr. Mullan traveled to Skullyville, Oklahoma to visit the old Choctaw cemetery where those who contributed to Irish famine relief were buried. He met with Choctaw Chief Hollis Roberts and invited him to lead AFrI’s third annual Great “Famine” Walk in Doolough in May, 1990.

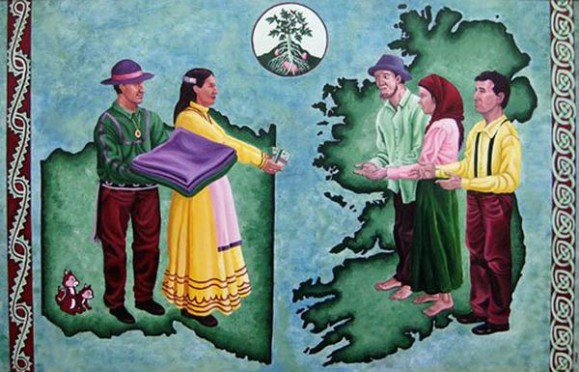

In his letter of invitation to the Choctaw, Mr. Mullan stated, “Our invitation to the Choctaw Nation to lead the first [Doolough] walk of the 1990’s (a decade during which we will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Great Famine), is in recognition of the great generosity your forebears showed to the Irish during their darkest hour. When the $170 contribution of the Choctaws to Irish Famine relief is considered against the background of your own “Trail of Tears,” just one decade earlier, it expresses something very deep and precious about your forebears’ humanity. It is a lesson for all humanity as we move towards the 21st century.”

The 1990 Doolough walk adopted the name ‘The Trail of Tears,’ underscoring the commonality between the Choctaw and Irish history. Over 800 people joined in the event, broadcast in over 120 countries worldwide. Following the Walk, Chief Roberts stated, “It is my hope that the relationship between the Irish and Choctaw will be an enduring friendship, starting new traditions and enriching the heritage of both cultures.”

The forcible removal of the Choctaw is euphemistically known as the “Trail of Tears.” It was in fact a 500-mile genocidal death march from Choctaw ancestral lands in Mississippi to Oklahoma. The Choctaws were forced to make that journey in 1831 as a result of the U.S. Government policy of Indian removal during the Presidency of Andrew Jackson (himself a son of Irish immigrants). The “Five Civilized Tribes” inhabiting the Southeastern U.S. (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek, Seminole) were forced to move to the Oklahoma Territory, under pressure from white settlers who had encroached on their lands in violation of existing treaties. The Choctaw were the first to depart. Unprepared for the hardships of the journey, begun in December (one of the worst winters the South had seen), more than half the Choctaw population died of starvation, exposure and disease (cholera epidemics, smallpox and dysentery). Their tribulations were compounded by unscrupulous government contractors and soldiers who accompanied them and sold them rancid food and liquor at extortionate prices. The final insult was that the U.S. Government made the Choctaw pay for their removal expenses.

In 1847, only 16 years after the beginning of Choctaw Removal in 1831 (a process which lasted through 1849), the Choctaw learned of the plight of the Irish people 4,000 miles away. The Arkansas Intelligencer and Niles Weekly Register (which syndicated the article from the Intelligencer) recorded a meeting in Skullyville (capital of the Choctaw Nation in the Oklahoma Territory) where a collection was taken to assist the victims of the Potato Famine in Ireland. Though a discrepancy in the amount collected exists (some historical accounts state $710 while the figure Mr. Mullan deciphered from poor quality Intelligencer microfilm is $170), money was raised in a remote Oklahoma town by Indians for Irish famine relief.

The deprecatory account in the April 3, 1847 Arkansas Intelligencer reveals the prevailing patronizing attitudes of the white population towards the Choctaws’ act of charity and the Irish poor. Headlined “The Choctaws Gift to their White Brethren of Ireland,” the article stated, “A meeting for the relief of the starving poor of Ireland, was held at the Choctaw Agency… after which the meeting contributed $170. All subscribed, Agents, Missionaries made up by the latter. The ‘poor Indian’ sending his mite to the poor Irish…What an agreeable reflection it must give the Christian and philanthropist to witness this evidence of civilization and Christian spirit existing among our red neighbors. They are repaying the Christian world for bringing them from out of benighted ignorance and heathen barbarism — not only by contributing a few dollars — but by affording evidence that the labours of the Christian missionary have not been in vain. They send their testimony to afflicted Ireland.”

The only other 19th-century reference chronicling the Choctaw act of generosity to the starving Irish is found in The Voyage of the Naparima, based on the diary of an Irish schoolteacher from County Sligo. Gerald Keegan, with his fiancee, fled the Famine in 1847. They took passage on the Naparima, one of the many dilapidated hulls transporting Irish to Canada and the United States on the Irish “Trail of Tears.” Keegan’s March 13, 1847 entry recounts how people in “the outside world” had responded to the tragedy of mass starvation in Ireland. He reported that the Sultan of Turkey, the working people of England, the Czar of Russia, the Emperor of China, local potentates in Egypt and India and the Jewish people of New York City sent contributions to relieve the suffering.

Keegan’s final notation was: “Among the donations from various parts of the world there is one that is singularly appreciated. It comes from a small tribe of native North American Indians, the Choctaw tribe from central western United States. These noble-minded people, sometimes called savages by those who wantonly released death and destruction among them, raised money from their meager resources to help the starving in this country. This is indeed the most touching of all the acts of generosity that our condition has inspired among the nations.”

The modern links between the Choctaw and Irish, spawned by Mr. Mullan’s initial contact, continued to grow. In 1992, the Lord Mayor of Dublin unveiled a specially commissioned plaque (sponsored by AFrI) in Dublin’s Mansion House commemorating the generosity of the Choctaw and Canadian Indians to the Irish in 1847. During that same visit, Irish President Mary Robinson welcomed the Choctaw delegation and Chief Roberts’ representative conferred the title “Honorary Chief of the Choctaw Nation” upon President Robinson (the only woman so recognized in the history of the Choctaw). In May of this year, the President visited the Choctaw headquarters in Oklahoma, and in a speech that once again linked the Irish and the Choctaw, she said, “The pain and suffering and loss caused by the dreadful famine in Ireland nearly a century and a half ago, have created an indelible record in the folk memory of our nation. We will always remember with gratitude, however, the compassion and concern displayed by the Choctaw Nation who, from their distant lands, sent assistance to the Irish people at that sad time. It has been my great privilege to be made an honorary chief of the Choctaw Nation and I am conscious that the honor bestowed on me will help to keep alive, in your country and in mine, the memory of their noble deed. … As the Choctaw people were so moved by the Irish plight so long ago, let us today be aroused to extend a helping hand to our brothers and sisters who are in need.”

Both the Choctaws and the Irish (through AFrI), did just that. The experience of the Doolough March and the modern-era solidarity spawned by the recognition of a shared experience in tragedy prompted them into a positive response to a then-current famine catastrophe. In September 1992, the Choctaws and AFrI joined in a re-enactment of the Choctaw “Trail of Tears” from Oklahoma back to Mississippi to raise funds for victims of Somalia’s “Great Famine.” Choctaw artist Gary White Deer, who designed the commemorative T-shirt for the occasion, wrote “My mother is part Irish and it will be a great and wonderful thing if we reaffirm the bond between our two peoples by helping to feed the People of Somalia. We will be feeding our own spirits as well. … Our shared histories keep telling us this.” The Choctaws also published The Choctaw and Irish Food Facts-Friendships Cookbook, which listed 200 Choctaw and Irish recipes. The book also provides historical facts about the Trail of Tears and the Potato Famine, and an account of how the destiny of two peoples had become intertwined.

Two disparate cultures, worlds apart, drew strength from each other. In sanctifying the memory of their dead, both groups were able to find solace in each other. When this sorrow is expressed in an empathic linkage, it transforms the human condition, and elevates that sorrow to a celebration of a common humanity. The Choctaw-Irish friendship can serve as an example for all people to reach out to others, for the trail of tears of one community leaves no people untouched. ♦

_______________

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the September / October 1995 issue of Irish America. Notably, the Great Famine Walk from Doolough to Louisburgh continues to this day. After two years of being virtual the walk returned to Mayo in May of 2022.

For over a century before Oklahoma was opened to homesteaders, members of the McCurtain family had served as Chiefs of the CHOCTAW tribe. The last on of these was Greenwood McCurtain, and it is from him that McCurtain Counry, Oklahoma, gets its name. I have had the pleasure of visiting a McCurtain family in CA who lost a son in Vietnam.

What a beautiful story I have to admit it is the first time I ever heard this what an amazing act of kindness from people who had so little.

What an extraordinary story of kindness. Their generosity and courage must never be forgotten.

I only learnt of this story yesterday when I read an article in the Guardian. I have been living in France for many years but, even in my childhood, I never heard of it.

It restores one’s faith in humanity to hear that the Choctaw people who had suffered to much and had so little could make a contribution to trying to ease the suffering of the Irish during the Great Famine. When extraordinary kindness and generosity.

And in a striking gesture to return the kindness during this pandemic ….. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/coronavirus-irish-donate-to-hard-hit-native-americans-to-repay-famine-aid-1.4245807

I read this last year and loved it.

That’s not what real Choctaw people look like. Real American aborigines are “black” people. We didn’t come on slave ships from Africa. We were already here. We’ve always been here. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2010-7081-586

“Real” Choctaw people come in all colors. Some are black. Some are brown. Some, like myself, have have blonde hair and blue eyes. That is what assimilating does. I am a member of the Choctaw nation of Oklahoma, and I am just as real as you. We are a tribe that celebrates our diversity. Love more, judge less.

????????

If you think about it too, all “races” have varied skin colors. The popular desire to define groups as a race based upon a few traits is scientifically inaccurate.

I am a quarter Cherokee/Choctaw. A quarter Iberian. The rest Irish and English/Scandinavian.

Such a mutt that of course I have dark blonde hair and hazel eyes. But if you look at my shapes—eyes, hair, body—I am not solely English, as my family and where I was raised will only allow me to identify.

It is easy to say “everyone was black at some point, so this is better,” to try and swing the pendulum back. But the truth is the human Race is all related and complicated and beautiful. That’s it, that’s the end.

That said I would love to be around groups I identify with other than just English, to know myself more.