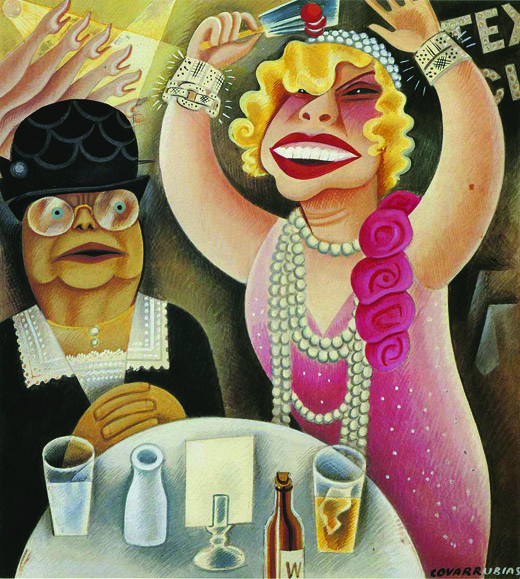

Singer, showgirl, and queen of the speakeasy during Prohibition, Mary Guinan was a genuine Irish American wild woman. Larger (and louder) than life, she had an even bigger heart.

During the wild and jazzy New York of the 1920s, Texas Guinan was the wildest and jazziest dame in town. Born Mary Louise Cecilia Guinan in 1884, her parents were immigrants from Ireland who settled in Waco, Texas. They sent Mary to the Convent of the Sacred Heart, but even the good sisters couldn’t contain her sass or the boisterous voice that drowned out the rest of the church choir. One can only imagine the anguish these nuns suffered years later when Mary/Texas became, with the exception of some husband-killers, the most notorious woman in New York.

By the age of 15, she was already a star in a Wild West show and, too much a powerhouse for a modest name like Mary, became known as “Texas.” By the time she died at 49, she had, thanks to her manic energy, led a life crammed with crazy careers – she was a daredevil in the rodeo circuit, a comic/singer in vaudeville, a chorus girl/actress on Broadway, a writer of shows, film’s first cowgirl, and a spokesperson, despite her slim frame, for “Marvelous New Treatment for Fat Folks.” But her greatest fame, her biggest star turn, was as the Mistress of Ceremonies in nightclubs, or, to put a less hoity-toity spin on it, an emcee in speakeasies, joints she co-owned with gangsters.

While Texas was still a reckless and restless rodeo star, she married a newspaper man, a union that left her still reckless and restless, but now, bored. She heard the call of her one true love, New York City – “I would rather have a square inch of New York than all the rest of the world.” Offloading her husband – “it’s the same man around the house all the time ruins matrimony” – Texas, penniless, hoofed it to New York.

But success came easily to Texas: her great figure and long gams soon put her in a Broadway chorus, then her wise-cracking persona netted her speaking parts in comedies. Starring in some popular fluff called The Gay Musician, she accidentally shot herself. Texas had already discovered the power of publicity (“exaggerate the world,” she would say). She used that mishap for self-promotion, announcing to newspapers, “Not even a bullet can stop Texas Guinan!”

Having established something of a name for herself, she took her act, a curious stew of singing, rope tricks and cornfed patter, on the national vaudeville circuit. It didn’t take long for a Hollywood talent scout to offer her a movie contract, traditionally the dream of all young, aspiring actors. But not Texas. Instead of being thrilled, she was dismayed – California was too far from New York. But, loving a challenge (and moolah), she conceded and became a star in Westerns, silent one-reelers.

Her first movie was, fittingly, The Wildcat (1917), followed by 36 more (a number she inflated to 300), and in each she was the hero, a rootin’ tootin’ gunslinger, a self-reliant cowgal who did her own stunts and took control of her career too. She started her own production company, controlled casting and supervised distribution.

As if being a Hollywood star didn’t have enough pizzazz, Texas, now a seasoned dissembler, again played the press and came up with a line of hooey that deleted her very public movie career. Texas, who had never been on a plane, claimed to have been a fighter pilot in World War I. Her service was so valiant that a French general, a hero at the Battle of Marne, awarded her a big (but nameless) medal. She got away with the tale, fact-checking not being very scrupulous back then since it could ruin a good story. The press and public embraced her as a war hero, managing to forget the movies she had made, in America, throughout the war.

In 1920, she announced she’d had it with “kissing horses in a horse opera” and was going home to New York. In that same year, the 18th Amendment, Prohibition, was passed, and dreaded by most Americans as a gloomy sentence to a dry purgatory. But newly prosperous and sophisticated New Yorkers had no intention of giving up alcohol and made illegal drinking and the clandestine underworld of the speakeasy fashionable. A new culture emerged, a heady mix of Broadway, movies, high society, politics, and freewheeling flappers, all who blithely broke the law and socialized with the gangsters who supplied the fuel that kept the party going. It must have been the so-called “Luck of the Irish” that Texas’s return to New York coincided with the new law. Prohibition proved to be her golden opportunity.

Texas wasn’t back long when she met creepy bootlegger Larry Fay at a social gathering. Fay watched on as she brought a moribund crowd to life – once she began wisecracking and singing, the funereal atmosphere lifted and an out-of-control party began. Truly this was a girl who just wanted to have fun and wanted the crowd to join along with her. Fay saw a star and kept his eye on her until he offered her a partnership in his establishment, the Club El Fey.

Texas re-invented herself yet again. At last she was able to monetize her gab, vibrant personality, and endless audacity – in one 10-month period, she raked in $700,000 ($6.4 million in today’s dollars). She was rich and extravagant and generous, spreading her good fortune with everyone close to her. She was given to shouting, in the middle of her crowded nightclub, “I love Prohibition!” And really who could blame her? Texas became an icon of the excess and abandon of the Jazz Age, and although she loved watching her customers get soused, she never touched a drop.

She would sit on a high stool in front of the band, draped in revealing gowns of velvet, dripping in diamonds and ermine and occasionally blowing a police whistle or foghorn. Texas was the first comic to insult her audience, sparing no one, not even the scary gangsters sitting at ringside. All were greeted with “Hello, suckers!” Out-of-towners were reduced to “butter and egg men” and, as the night wore on, she would taunt, “You may be all the world to your mother, but you’re just a cover charge to me.” She ordered her audience to cheer on her scantily clad dancers, “Give the little ladies a big hand.”

It was Texas and only Texas who had the magnetism to bring in the crowds. Her clubs became a rarefied universe, everyone was there to see and be seen – Babe Ruth having a snootful, Eugene O’Neill holding forth, Damon Runyon listening with an ear toward re-using her banter, George Gershwin sitting in with the band, and George Raft, the Charleston King-turned-movie-gangster, taking over the dance floor. Once, during a raid (and there were lots), Texas put an apron on the Prince of Wales and had him pose as a dishwasher. Fat cats from Wall Street, the Social Register swells, rubes from Indiana, and college kids all paid Texas’s exorbitant cover charge and drank her overpriced drinks.

One night, Aimee Semple McPherson, famed Evangelist and faith healer, wafted in and gave a rowdy crown the “What Shall it Profit a Man” sermon. At Texas’s urging, the audience applauded, then the two women indulged in a sisterly embrace. In truth, Texas and Aimee – one earthy, the other ethereal – were alike. Each carefully curated her image, Aimee with her marcel-waves and celestial white gowns; Texas in glitzy dresses, jewels, and a wild head of curls. Both were master manipulators of the press and given to big, fat lies – Aimee faked her own kidnapping and Texas claimed she was a war hero who served only ginger ale at her club.

Although she was now, officially, the “Queen of the Nightclubs” and making a fortune, it wasn’t enough to continue her partnership in the high life with the low-life Larry Fay. She wanted out and, knowing she was the ballsier of the two, told Fay to vamoose, she was sick of him and his horsey kisser. Not surprisingly, the psychopathic mobster didn’t take well to her dismissal and spat out a series of threats. Texas, usually fearless, now hired bodyguards and an armored car, but finally reached out to her best defense, her team of even more powerful psychopathic mobsters: Owney “The Killer” Madden, Dutch Schultz, “Big Frenchy” Dement, and Hyman “Feets” Edson. Faced with this line-up, Fay backed down and sent Texas flowers.

Her biggest success was the 300 Club, and as the nights raged, they were raided almost constantly. Of course, a lot of these raids were for show as she routinely bribed (and entertained) the police. But a new crop of dry agents landed in town, making Texas their number one target. One night in 1927, a battalion of police and federal agents raided the 300 Club. As soon as Texas saw them she ordered the band to play “The Prisoner’s Song” to provide background music during her arrest. A policeman used the opportunity to make a wisecrack of his own, ordering his men, “Give the little lady a big handcuff.” But Texas spent only one night in jail, time she passed by singing “The Prisoner’s Song” as her chorus girls joined in on the chorus. The incident got headlines, the story even making it to the New York Times: “Freed on $1,000 Bail with Nine Employees After Nine Hours of Mirth in Cell.”

The raids continued, but as soon as one joint closed another opened, and a list of her establishments, not including the El Fay and 300, includes the Hotsy Totsy, King Cole, Athena, Club Royale, the Miami Del Fey, Melody Club, Abbey, Argonaut, and the Texas Guinan Club. Besides being raided for violation of the Volstead Act, she was once arrested for showing “pornographic” entertainment, a reference to the costumes worn by her 40 fan dancers. The police produced, as evidence, their six by three inch costume. Texas argued her own defense, claiming it wasn’t the costumes but the stage that was “too tiny.” As usual, she beat the rap.

In between closings and re-openings, Texas would retreat to her Greenwich Village apartment, close the heavy drapes, and sink into her bed that housed many pillows, books, and perfumed dolls. And always, her mother, father, and beloved brother, Tommy, were close by. She also relaxed with her good friend Mae West, and the two blondes were often confused with each other – both were buxom, bawdy feminists who served time in jail for breaking boundaries and the law. Mae and Texas would hold séances together, the most famous being their attempt to speak with the recently departed Rudolph Valentino. Instead, they conjured up Arnold Rothstein, the man who fixed the 1919 World Series. When, much later, the reluctant Rudy arrived, it was only to warn Mae (and, strangely, not Texas) that she had enemies.

When Texas put together a review called “The Padlocks of 1927” that same year, it flopped, as did the movie The Queen of the Nightclubs, a 1929 talkie where she played herself. Her ever-rising star was suddenly slipping as she seemed passé, just another showgirl gone to fat. But 1929 produced a bigger flop, the crash heard round the world, and Texas, like everyone else, lost a fortune.

Not even the Great Depression got her down. She pulled herself together and took her dancers to Europe where, unfortunately, her racy reputation preceded her. Texas was denied entrance into England and even France, the land that gave the world the Folies Bergère, wouldn’t let her in. The real reason wasn’t her morals (or lack of), it was simply that these countries didn’t want competition from abroad, native performers having a hard enough time getting work. Texas, taking advantage of the publicity her non-existent “tour” generated, twisted the truth to create a show, “Too Hot for Paris,” which she took on the road once back in North America.

In the fall of 1933, Texas began suffering severe abdominal pain, but still performed four shows a day. Finally she collapsed, and doctors diagnosed her with a most unglitzy disease, amoebic dysentery. Shortly afterward, the life of the party died. But not before giving instructions to have her body returned to New York – “better a lamppost on Broadway than the brightest star in the sky” – and ordering that her funeral be spectacular. And it was, Depression be damned. Texas was laid out in white chiffon, a rosary in one hand, a giant diamond ring on the other. At her request, the coffin was open “so the suckers could get a good look without a cover charge.” Upwards of 12,000 fans came to see her off. One month to the day after her death, Prohibition also died, as the 21st Amendment nullified the 18th.

Years earlier, she had chosen her own epigraph, an excerpt from an Oscar Wilde poem, a verse so unlike Texas and her wild life that it raises the question, “Just who was that blonde dame?”

And down the long and silent street,

The dawn, with silver sandaled feet,

Crept like a frightened girl. ♦

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co- writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

This biographical story about “Texas” Mary Guinan was totally entertaining, a true, well-written delight to read!

I realize that this comment is being made quite a while after the publication of this article but I only found it today. I just wanted to say that I think that the epitaph at the end is very appropriate. Unfortunately, the entire poem, Wilde’s “The Harlot’s House” is too long to be put on the stone so she had to choose the climax of the poem. The poem itself tells of a wild, hectic party which a young woman chooses to join. It goes on all night only to dissipate with the coming of day.. Ms Guinean realized that, just as dawn brings an end to the wild times in the Harlot’s House, her passing would bring an end to her wild party.

The article is excellent and very entertaining.