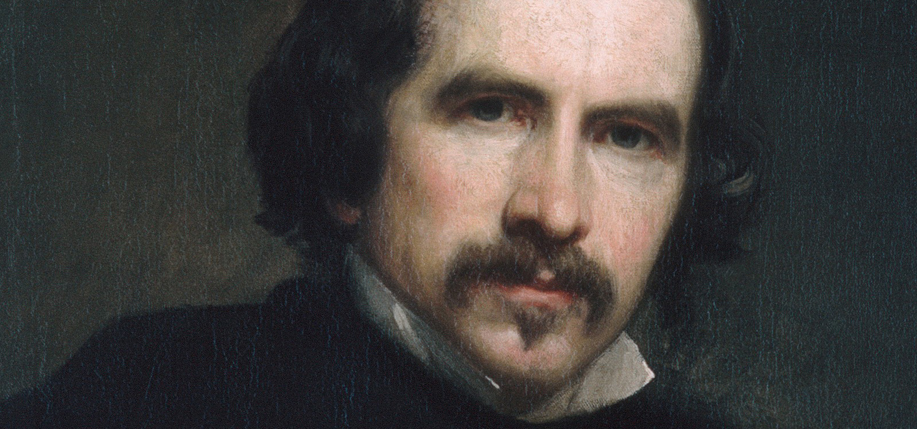

America’s most prolific 19th century portraitist, whose painting of Abraham Lincoln hangs in the State Dining Room at the White House, was an Irish American born into poverty in Boston.

There are more portraits of American presidents hanging in the White House by George Peter Alexander Healy than any other artist, yet amazingly he remains a largely unknown figure to many Americans. In his day though, he was one of the most acclaimed American artists, with a number of American presidents posing for him, including John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, James Polk, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Chester A. Arthur. He was not only a great painter, but also prolific. Working incessantly, he produced hundreds of portraits of the most famous men and women of his day, including kings, the 19th century’s greatest artistic figures, and Pope Pius IX.

Perhaps the only thing more amazing than Healy’s talent is his improbable rise from poverty to artistic greatness. Born in Boston in 1813, Healy was the oldest of five children. His Irish grandfather had been ruined by the rebellion of 1798 and Healy’s father, Dubliner William Healy, was forced to leave Ireland, becoming a midshipman with the East India Company. He eventually ended up in Boston as the captain of a merchant vessel. He married an American Protestant woman, Mary Hicks, a Boston native of English descent.

In his 1894 autobiography, George Healy recalled his father in both romantic and realistic terms: “He was a bold-spirited, imprudent man, excellently well fitted for the adventurous life he led,” though he also noted that his father “was not suited for a landsman’s life; he was a sailor and nothing but a sailor, and each of his subsequent ventures proved disastrous.”

One of Healy’s biographers noted the romantic Irish influences in his personality he inherited from his father, stating, “The Celtic strain ran bright and lovable through the temperament of the son.”

A loving son who adored his mother from an early age, Healy was aware of his family’s poverty, doing any odd job he could to bring money to his impoverished, suffering family. No one could have imagined Healy would become an artist, least of all the painter himself, who recalled later, “I should have been surprised had anyone predicted my future career.” He first began painting at sixteen and immediately fell in love with art. When he confessed to his grandmother his desire to paint professionally, she discouraged him, warning him that he would never become a successful artist. But Healy was a determined and persistent man.

Boston in 1829 offered little help to aspiring artists. Healy recalled, “In those days there were neither academies, nor drawing classes, nor collections of pictures to be studied.” What he lacked in training, however, he made up for in perseverance, working hard to train himself in the skills of a painter. He opened a studio in Boston and succeeded in getting one of the most prominent Boston society doyens – Sally Foster Otis, the wife of politician and businessman Harrison Gray Otis – to pose for him. Otis, in turn, got him other important commissions.

Healy knew that the only place for an aspiring painter was Paris, and in 1834 he sailed for Europe, despite the fact that he neither spoke French nor knew anyone in the French capital. Before he left, he had the chance to meet the inventor of the telegraph, Samuel Morse, who was also a portrait painter. Morse discouraged him, saying, “So you want to be an artist? You won’t make your salt.” Healy coolly replied, “Then sir, I must take my food without salt.”

Healy entered the studio of Baron Gros as the only American studying with the great French master. He worked hard and not only mastered French, but became a highly proficient artist. His painting style was essentially French. He became adept at coloring, his management of light and shade was excellent, and he learned to draw well-outlined likenesses. His paintings were rugged and forceful and he developed a style of portraiture that accented his fine draftsmanship, naturalistic coloring, and smooth, finished surfaces.

Word of his talent spread. Lewis Cass, the American minister to France, asked Healy to paint a portrait of him and his wife, which later would win the artist his first medal at the Paris salon. On the strength of his growing reputation, Healy traveled to paint in London where he met his future wife, Louisa Phipps. The couple returned to Paris where Healy embarked upon the beginning of a long and happy marriage and a thriving career.

Cass showed Healy’s portrait to the French king, Louis Philippe I, who was so taken with Healy’s canvas that he asked Cass to arrange for the American to paint him. The king was delighted with Healy’s royal portrait, which deftly portrayed the king in his army uniform as a man of military bearing, clearly fit to rule a country. But more than a great painter, Healy was also affable and genial. Louis Philippe soon took a liking to the talented young American, and with the French king as his patron, Healy’s career soared.

The king asked Healy to return to the United States to make a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s iconic painting of George Washington and to paint the most famous Americans of his day. Impressed with his royal patronage, men like Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams sat for the Irish-American painter. Suddenly, though at the height of his success in 1848, there was a revolution against Louis Philippe. The king abdicated and Healy’s royal patronage instantly disappeared.

He returned to Paris and decided to paint a monumental work that would take him two years. His canvas, “Webster’s Reply to Hayne,” was a gigantic 15 by 27 foot painting showing Senator Daniel Webster addressing a packed Senate in defense of the Constitution. The canvas had 120 identifiable faces, each head on the vast canvas a portrait in its own right. Healy returned to America with the huge painting, but it received less than glowing reviews and eventually he sold it to the city of Boston for half of what he had previously thought the canvas might fetch. Today, the acclaimed canvas occupies the most prominent spot in the great hall of Boston’s Faneuil Hall.

Healy, though, was never one to be discouraged. He returned to Paris and completed one of his best paintings. His “Franklin Urging the Claims of the Colonists before Louis XVI” gained him a second-class gold medal at the Paris International Exhibition of 1855 and is still regarded as one of his masterpieces.

He had lived in Europe for more than 20 years, yet he had never lost the idea of returning to America. In 1855, Healy made the acquaintance of William B. Ogden, who has been called the “father of Chicago.” Ogden befriended the painter and urged Healy to visit him in Chicago. Healy arrived and soon fell in love with the “garden city,” determining to make Chicago his home.

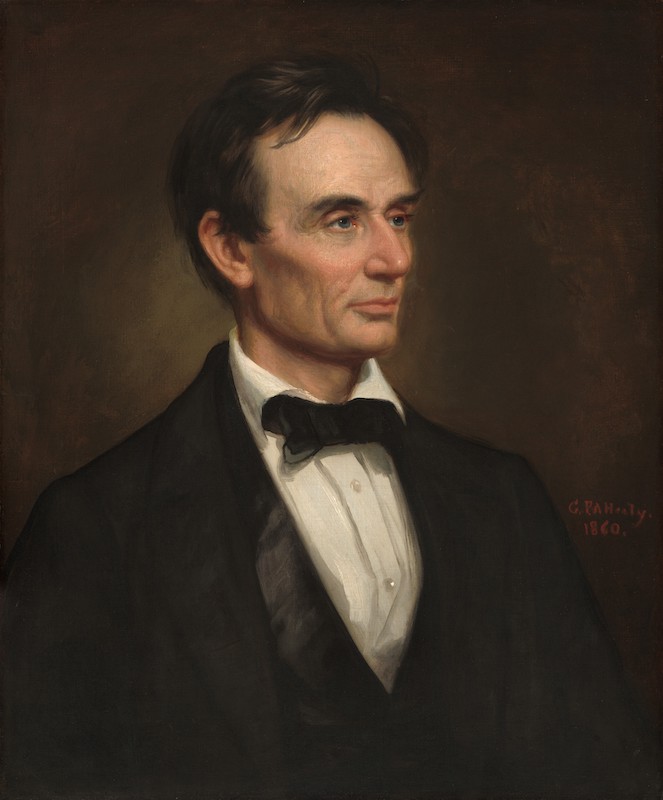

He quickly became the city’s most famous painter. In 1860, Chicago businessman and philanthropist Thomas B. Bryan commissioned him to paint the portrait of then president-elect Abraham Lincoln, an Illinois native son. Healy traveled to Springfield and met Lincoln, who told funny stories all during his sitting. Lincoln read a droll letter to the painter in which a woman complained of the president’s ugliness, while asking him to grow a beard to hide his gruesome features. Lincoln asked Healy if he could paint him with a beard, but Healy refused. The painting, which today hangs in the National Gallery, is a masterpiece and shows the beardless youthful man still unaffected by the stress and burdens of the Civil War.

An ardent Unionist, Healy happened to be in Charleston at the beginning of the Civil War and he had to flee in order to escape being tarred and feathered. Deeply appalled by the murder of Lincoln, after the war Healy painted some of the most iconic images of the president. One of his greatest works, which now hangs in the White House, is called “The Peacemakers” and depicts the war’s only three-way meeting of President Lincoln, General Grant, and General Sherman, as well as the U.S. Navy’s Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter. Years later, President George H.W. Bush commented on his admiration for the canvas in a speech:

“In it you see the agony and the greatness of a man who nightly fell on his knees to ask the help of God. The painting shows two of his generals and an admiral meeting near the end of a war that pitted brother against brother. And outside at the moment a battle rages. And yet what we see in the distance is a rainbow – a symbol of hope, of the passing of the storm. The painting’s name: ‘The Peacemakers.’ And for me, this is a constant reassurance that the cause of peace will triumph and that ours can be the future that Lincoln gave his life for: a future free of both tyranny and fear.”

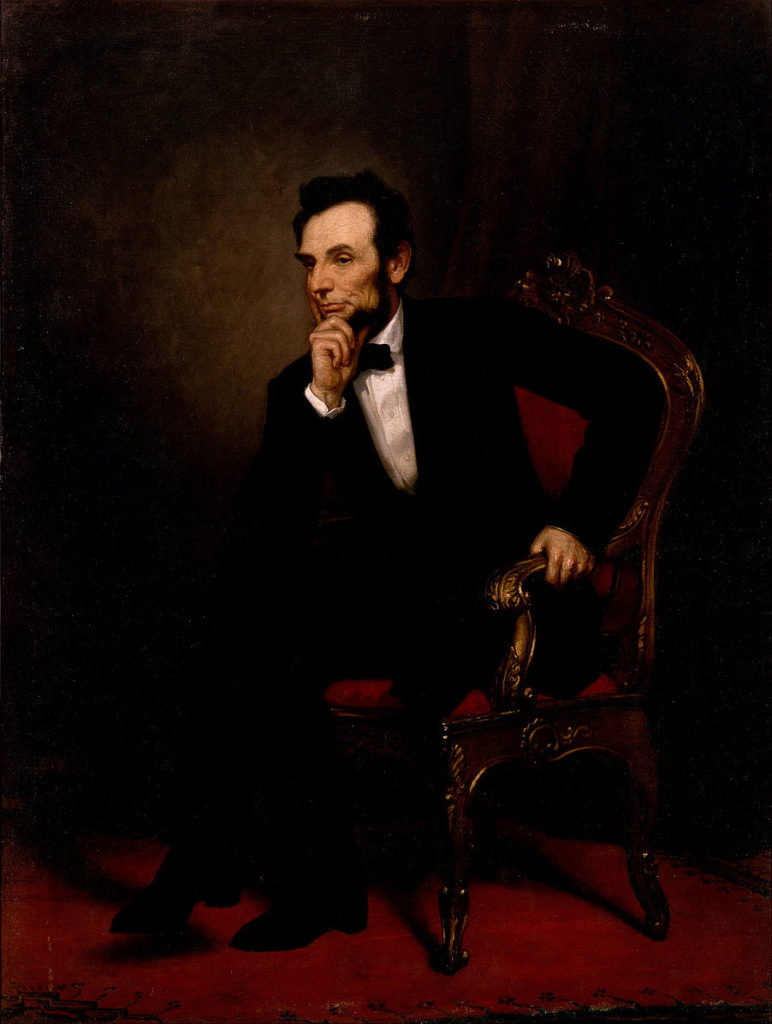

Ironically, perhaps his most famous painting, which now graces the State Floor of the White House, was initially rejected. In 1869, Healy painted a portrait of Lincoln that he sent to the White House to join a growing collection of presidential portraits. President Grant, however, did not like the canvas and selected another Lincoln portrait by William F. Cogswell. However, Robert Todd Lincoln, the wealthy eldest son of President Lincoln, bought the portrait, remarking later in life, “I have never seen a portrait of my father which is to be compared with it in any way.”

Seventy years later in 1939, the portrait finally made its way to the White House. When Lincoln’s granddaughter died, she left the portrait to the White House. On January 7, 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote to Frederic N. Towers, an executor of Mary Harlan Lincoln’s will, that it would give him “great pleasure to receive for the White House the Healy portrait.” Prominently displayed above the central mantel in the State Dining Room, millions of White House visitors have seen it. The portrait’s placement in one of the largest rooms on the State Floor and on the same axis as Gilbert Stuart’s well-known portrait of George Washington in the nearby East Room is a testament to Healy’s high rank in American portraiture.

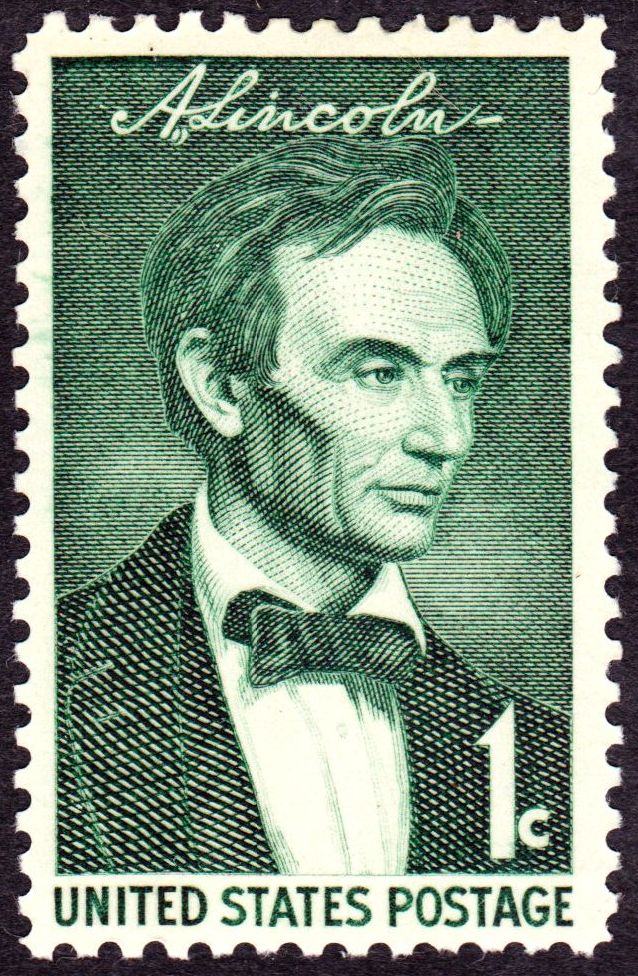

In 1871, Chicago’s great fire destroyed Healy’s home, and many of his paintings went up in flames along with the house. Healy, exhausted from years of relentless work and now also homeless, returned to Europe to lead a quieter life. However, the painter came back to his beloved Chicago just before his death in 1894. In 1959, 150 years after Lincoln was born, the United States Post Office commemorated the 16th president with a stamp bearing Healy’s iconic Lincoln painting.

Although time has dimmed his fame, Healy’s legacy of hundreds of paintings of America’s great men survives not just in the White House, but also in many of the most famous American galleries. The poor Irish-American boy from Boston remains one of the greatest American portrait painters. ♦

_______________

Geoffrey Cobb is a Brooklyn high school history teacher, writer of the blog Historic Greenpoint, and the author of Greenpoint: Brooklyn’s Forgotten Past (CreateSpace, 2015). He has lived in the same north Brooklyn neighborhood for over 20 years.

Wow, an excellent article, Mr. Cobb. Thank you.

Yes, I agree. This was truly a great essay! Thank you for writing it. A+

sincerely, geof

Nice post p….so much Knowledge at one place

Excellent history as always Mr Cobb, A wonderful insight into the painter and his subject. Amazing that two of these paintings are in the White House.

Three portraits by Healy are on display at the New Hampshire Historical Society.

The Peacemakers was acquired by The White House from somewhere in England in 1947.