Conor Lovett and Judy Hegarty Lovett, leading Beckett interpreters, and John Minihan, the photographer who captured Beckett on film, talk to Rosemary Rogers.

Samuel Beckett created the greatest body of literary work – novels, short stories, poetry, essays, and, most famously, plays for theatre, radio, and TV – in the 20th century. But the Irishman and his artistic output is often judged, unfairly, as too esoteric, too inaccessible. Perhaps it’s best not to analyze his work, instead just to give in to it, listen to the musicality of his language and, for a while, live in his absurd, tragic, and very funny universe. Inmates in prisons around the world – with little or no education – instinctively “get” Beckett. They’ve been staging and performing Waiting for Godot, the most emblematic story of waiting ever, for over 50 years.

A few years ago, the Classical Theatre of Harlem performed an outdoor Godot in a section of New Orleans devastated by Hurricane Katrina, a residential area with no residents. For the survivors, the play was hardly a “mystery wrapped around an enigma,” it was life. The production was explained by the artist Paul Chen: “There is a terrible symmetry between the reality of New Orleans post-Katrina and the essence of this play, which expresses in stark eloquence the cruel and funny things people do while they wait for help, for food, for tomorrow.”

While Beckett deplored his great success – he called his Nobel Prize a “catastrophe” and later gave away the earnings from his works – the earlier Beckett had despaired, convinced no one would ever want to read what he wrote, let alone pay for it. But after World War II and his brave service in the French Resistance, Beckett returned to Paris, a changed man. From 1947-1950, years he called “the siege in the room,” he began a period of his greatest productivity – he was, at last, freed of his demons.

And, he now began to write in French.

During “the siege” Beckett wrote three novels, Molloy, Malone Meurt, and L’Innommable. Today he is best known for his plays, but Beckett felt his prose fiction was his central work. The novels are complex, each one told by a disembodied voice, possibly three of literature’s most unreliable narrators. Beckett foregoes exposition, plot, and character descriptions; he doesn’t really expect the reader to understand what’s going on, but rather to just enter the psyche, “the relentless interior monologue we call the mind” of his odd characters. The narrators are stand-ins for humanity, confused souls who still manage to find humor in their despair.

THE INTERPRETERS

Leading Beckett interpreters, Conor Lovett and Judy Hegarty Lovett (he acts, she directs), recently dramatized the novels at Lincoln Center’s White Lights Festival. The couple, founders of Gare St. Lazare Players Ireland, brought The Beckett Trilogy to the stage in an unforgettable night of theater. Judy condensed, seamlessly, the novels into three excerpts and Conor’s one-man performance transforms Beckett’s voices into corporeal form as he acts each long text without a fumble. The audience soon forgets these scenes weren’t originally written for the stage and, for readers who have struggled with the trilogy, the novels magically come to life.

The Hegarty-Lovetts, Cork natives who now, like Beckett, relocated to France, have for the past three years been artists in residence at the Everyman Theatre in Cork. They were kind enough to answer some queries:

How was it possible to condense three novels into three dramatic scenes?

Judy: There was a great sense of the possible. We just jumped in and did it. The work is not driven by plot and narrative, so it felt easy enough to unravel the relentless interior monologue we call the mind.

The texts are so long, so complex, memorizing must have been a hard go.

Conor: The memorizing is slow work but it also gives me the opportunity to let the text get into me somehow. Any actor knows that you can only really make the text sing if you really know it.

Your one-man show brought to mind an ancient Irish storyteller, a seanchaí, but that’s an odd word to use for prose written in French.

Conor: Fintan O’Toole in the Irish Times referred to “the seanchaí unplugged” in reviewing our work. It’s a lovely idea because the seanchaí is already the very simple form of storytelling where a man or woman regales their audience with nothing but words. For me, the “unplugged” seanchaí is closer to Beckett’s world because there is no performance inferred, it’s just the consciousness often in freefall.

How were you able to put disembodied voices on stage?

Judy: We have always aimed for a non-representational delivery. We are looking for the audience to join the person before you who at times narrates the character, at times becomes the character and at times looks to be improvising the text. It hovers, it does not land.

It’s been said that Beckett considers the novels his best work. Thoughts?

Judy: The depth of emotion, philosophy, and pure human feeling in the work seems to suggest that he was an incredibly committed artist. I don’t see him so much as a novelist or a playwright or a poet, but as an artist who happened to use writing and words but also made pictures and performances.

What’s next?

Conor & Judy: We’re excited to bring our work to the Abbey Theatre in Dublin from April 11 to 14 this year and on tour in Ireland. It’s happening on Beckett’s birthday too, so it’s a great reason to be to Dublin.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER

The last book of the trilogy, L’Innommable (The Unnameable) ends with a famous Beckett quote, “You must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” Long after the writer had died, his photographer John Minihan was paying respects at Beckett’s grave in Montparnasse when he saw a piece of paper slipped aside the tombstone. It was a tribute from an anonymous fan that read, “Dear Sam, I’ll go on.”

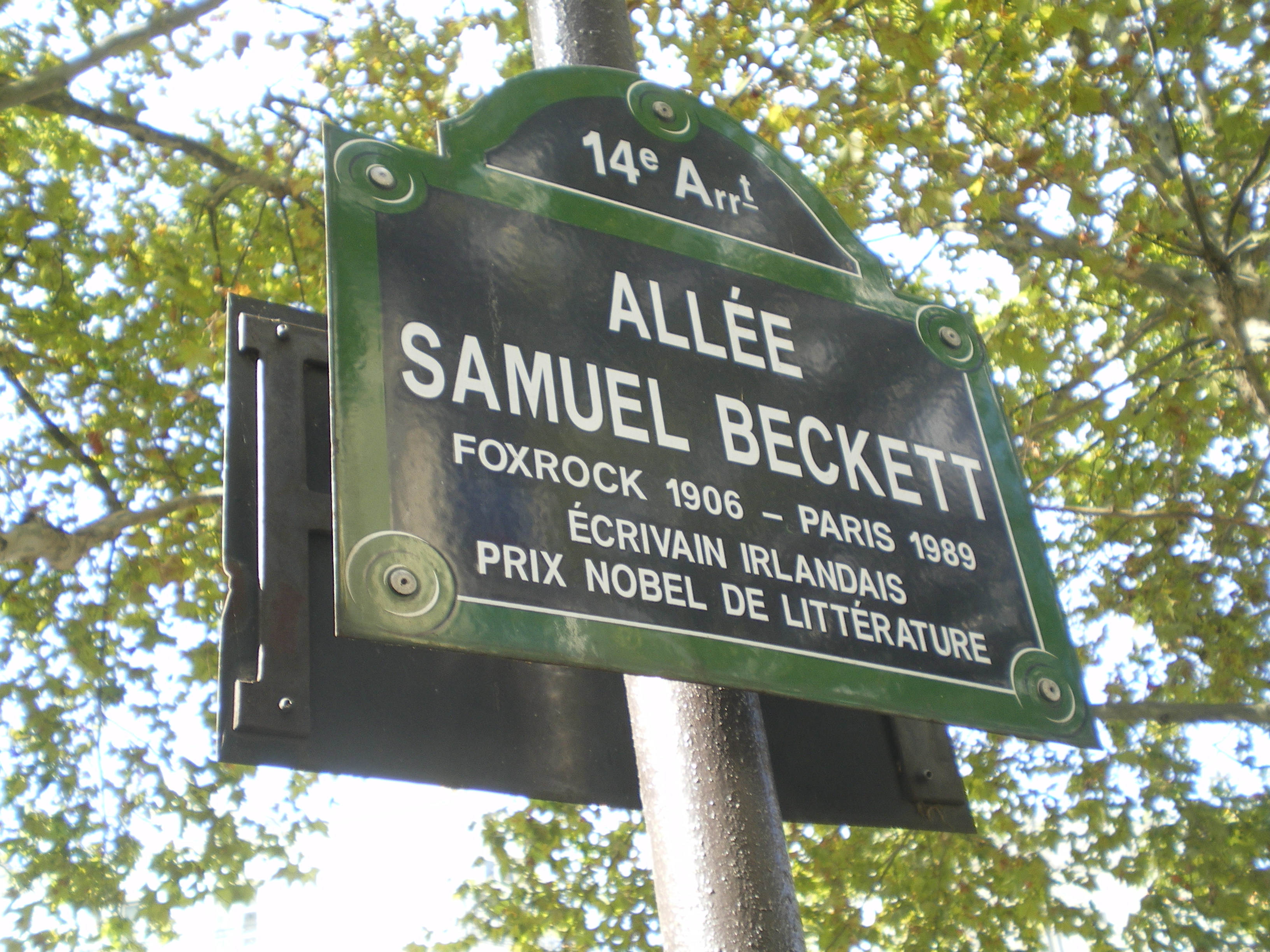

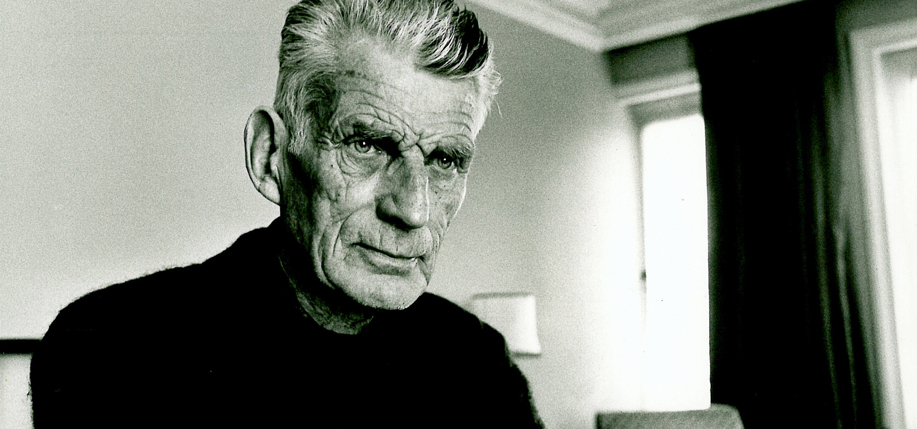

The first time Minihan heard Beckett’s name was in 1969 while he was working at London’s Evening Standard. A frantic editor was yelling to the picture desk – it seemed an obscure Irish writer by the name of Samuel Beckett had just won the Nobel Prize – and they had no photos of him. Minihan, a Kildare man, inwardly rejoiced. “It wasn’t the most fashionable time to be Irish in London, the IRA and all that. Then, out of nowhere, an Irishman wins the Nobel.” Minihan vowed to find him – “As an Irish photographer, it was imperative for me to photograph this Irish writer” – and, in the years to come, would shoot some of the most iconic photographs ever taken of Beckett. It helped, of course, that Beckett had one of the greatest faces ever photographed, especially in black and white.

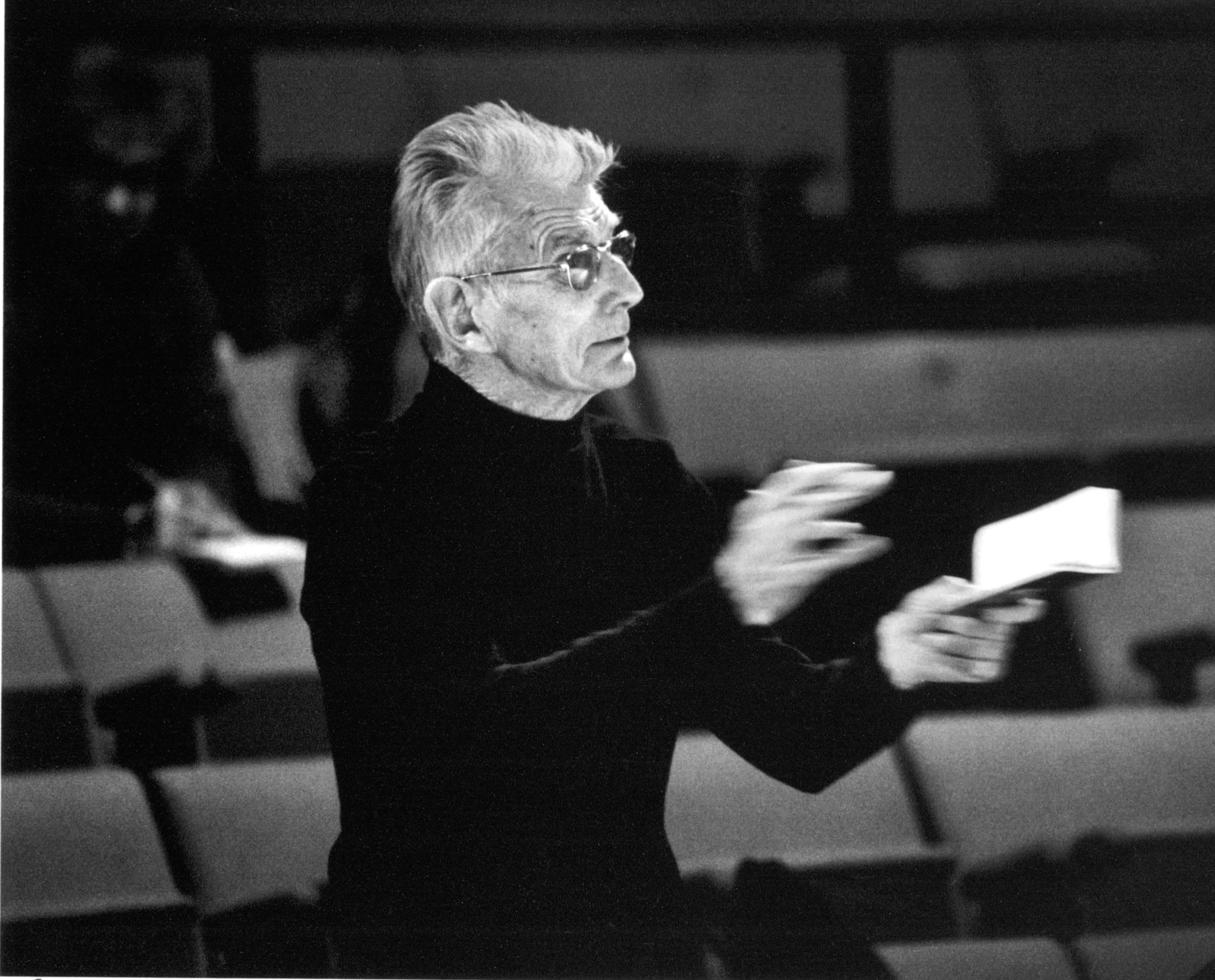

In 1980, Beckett was in London directing Rick Cluchey, the convict-turned-actor, and Minihan learned, via an Irish porter at the Hyde Park Hotel, that Beckett was staying in Room 604. He called, but the switchboard, at the instructions of the publicity-shy writer, wouldn’t put him through. The fast-thinking photographer left a note saying he wanted to show Beckett a series he had taken in his home town of Athy, Kildare, “The Wake of Katie Tyrrel.” The images were stark – the dead body of an old woman, the mourners at her wake, stopped clocks, covered mirrors. How could this not appeal to the man who wrote we are “all born astride the grave”? Minihan also included a grainy shot of two local men “who could have been Vladimir and Estragon” at a bus stop. Minihan knew his series “had Samuel Beckett all over it.”

Beckett took the bait and Minihan’s next call – “I heard a gentle voice, a soft Dublin accent, invite me up to Room 604.” The voice also asked him not to bring his camera, a request the photographer pointedly ignored. As Beckett looked over the Katie Tyrrell series, he remarked, “these are important pictures,” high praise from someone so reserved. At the conclusion of their meeting, Beckett motioned to Minihan’s Hasselblad, as if to say, “Get on with it” and posed for a shot. But their story didn’t end there, “Sam probably thought this was the last he was going to see of me, but I don’t operate like that.”

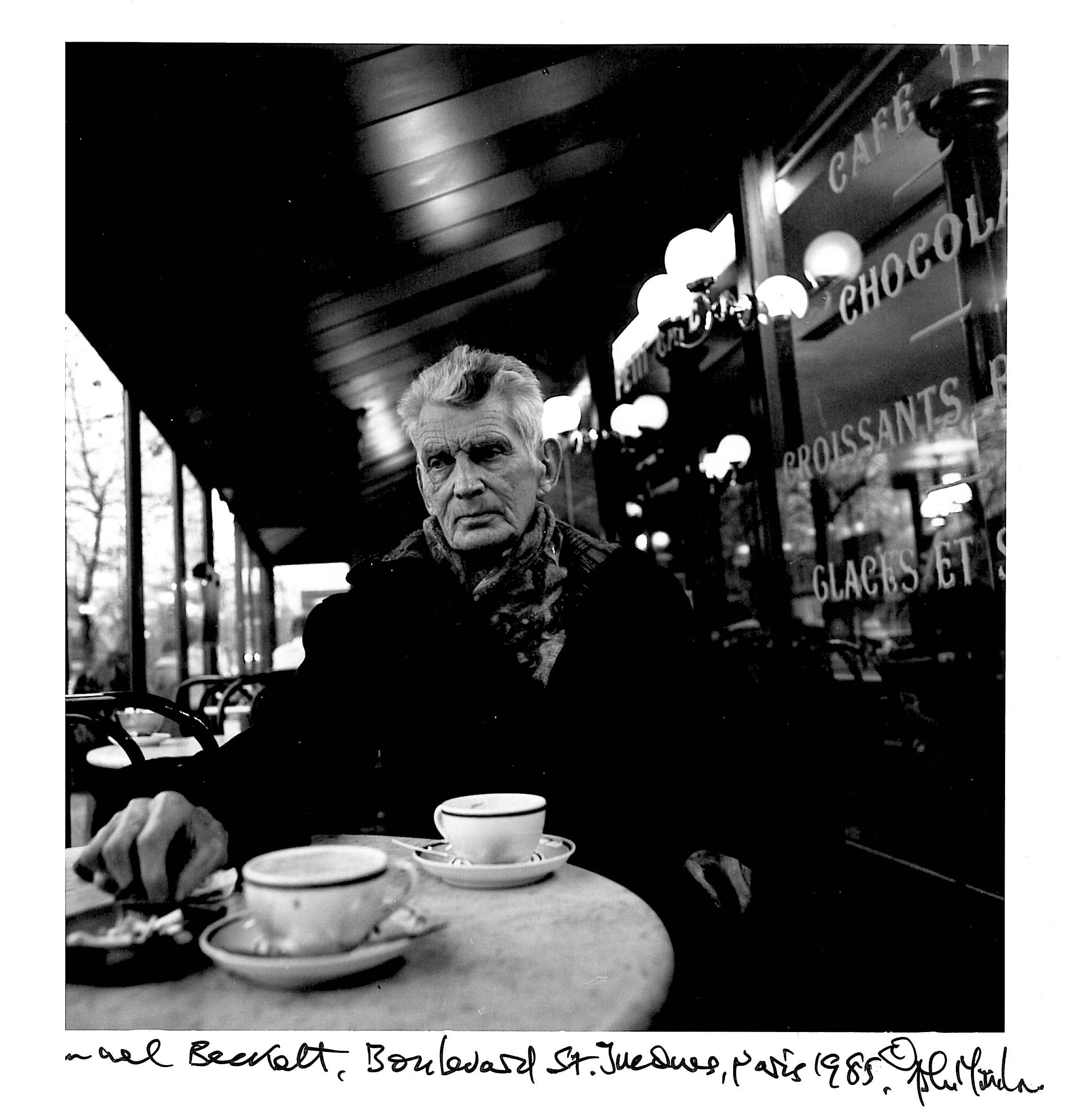

Their most important session was in Paris in 1985, a few months before Beckett’s 80th birthday. They had a 3:00 p.m. appointment at a cafe in the garish, touristy Hotel PLM (a place where no one would recognize a Nobel Laureate) on the Rue St. Jacques. Minihan arrived early to pick a table with good light and Beckett, ever prompt, arrived exactly at three. For two hours, they talked, drank, and smoked (Beckett’s) cigarettes, but as daylight faded Minihan began to panic. Finally, close to 5:00 p.m, the writer, in classic Beckett understatement,

announced, “You can take a picture now if you like.” As natural light leaves, artificial lights come on and Beckett seems to fall into a reverie, staring into space.

Minihan, in New York City last November to speak at the opening of his exhibition at the Irish Arts Center, said the resulting pictures were a narrative – Beckett in Paris – with the writer as director. “He wanted the picture to say, ‘This is who I am.’”

John Calder, Beckett’s publisher, paid Minihan a great compliment: his picture had caught Beckett and “the introspective, infinitely sad gaze of a man looking into the abyss of the world’s woes.” ♦

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co- writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

Leave a Reply