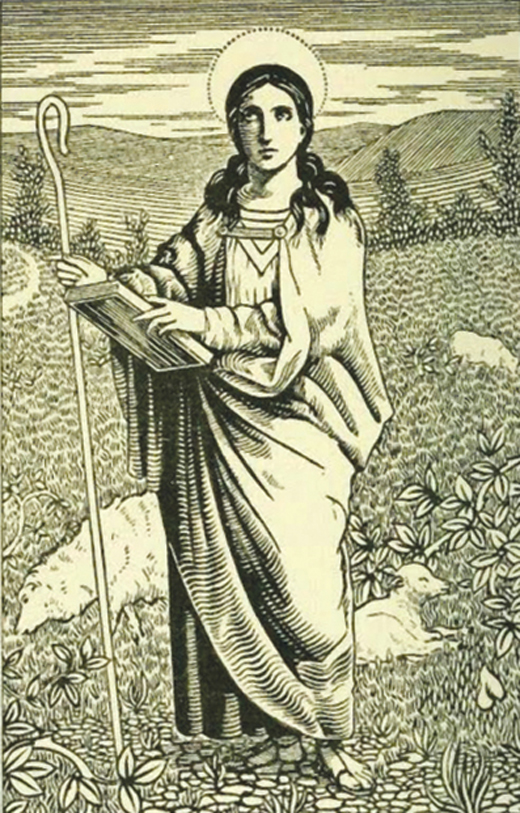

A nun, abbess, and founder of several monasteries, Brigid of Kildare was a woman who defied authority, possessed great strength of will and determination, and whose cheerful giving of food and shelter to any passing traveler laid the foundation for Ireland’s legendary hospitality.

Saints are everywhere, like enzymes, gravity, or the CIA – invisible, yes, but hard at work on your behalf no matter whether you’re Catholic or even Christian. This assemblage of visionary spinsters, ex-cons, levitating monks, beautiful-blond-virgin-martyrs, poets, and vampire killers hail from every nation in the world and have many devoted followers. But if you happen to be Irish, you may discover that saints have taken up permanent residence in your unconscious and embedded in your DNA. Who else but the Irish share the saints’ penchant for conflating paranormal activity with prayer or fusing facts with myths?

Ironically, Ireland, the “Isle of Saints and Scholars,” did not have a new saint from the 1225 canonization of Saint Lawrence O’Toole until 1975, when Blessed Oliver Plunkett, waiting in the wings for 300 years (and he was drawn and quartered too!) got the official nod. In those intervening 750 no-saints-for-Ireland years, Irish Catholics were persecuted and martyred for their faith and along the way, starved to death. It’s a mysterious snub, especially since the early saints traipsed all over Europe, converting millions. And the most radiant of all Irish saints was Saint Brigid, the “Mary of the Gaels.”

Sometime around 432, Saint Patrick (who gets all the press and parades) drove the snakes out of Ireland, a dubious feat since there hadn’t been snakes there since the Ice Age. But it was a powerful story, one he wisely used to illustrate his dispatching promiscuous pagans from the land. In another savvy move, the early Church “Christianized” Celtic deities, transitioning them into saints by retrofitting their biographies to include Christian attributes. Both Brigid and her Celtic namesake, Brigit, were associated with fire and, notwithstanding the saint’s virginity, fertility. Both were gifted in art, magic, poetry, and healing and enjoyed the same Feast Day, February 1.

And so began Christian Ireland. The fledgling Church followed the Roman civic structures and replaced tuaths with monasteries as the central units of administration. Since Ireland had no cities, monasteries were the population centers, places of secular and religious study. The monastic structure worked, thanks to the great abbots and one abbess who founded and led the first monasteries. They were now the new rulers, the new druids: Saint Columcille, Patrick’s successor with a quick fuse, Saint Cieran, Saint Colman MacDuagh, Saint Brendan (who still found time in the year 500 to discover America), Saint Jarlath, Saint Kevin (more on him later) and one wild Irish woman, Saint Brigid of Kildare.

It was those Irish monasteries that changed the course of Western history. After the fall of Rome in 476, barbarians ravaged Europe and its citizens, burning all books and art. Silent scribes, in silent monasteries on that isolated isle up north, grabbed every book they could find and took on the painstaking task of copying them all. As Thomas Cahill writes in How the Irish Saved Civilization, “Without the Irish monks, who single-handedly re-founded European civilization…the world that came after them would be an entirely different world, a world without books.”

Brigid’s story begins in the middle of fifth-century Ireland, where inquisitive angels were peeking into the cottage of a slave woman in childbirth, perhaps in the company of Saint Patrick, there to baptize the newborn. The mother, Brocseach, was a sometime concubine of her owner, a pagan chieftain named Dubtach, the son of the extravagantly-named Conn of the Hundred Battles who doubtless passed his fighting spirit on to his granddaughter.

Children of slaves in fifth-century Ireland, much like children of slaves in 19th-century America, were immediately separated from their mothers, and Brocseach was sold off to a rival chieftain. Still, Brigid grew bright and beautiful, attributes that overcame her ignoble birth and made her a favorite in her father’s household. Everyone admired her kindness and charity while awed by her acts of magic. But her real power was the strength of her will, determination, and open defiance of authority. She was in constant rebellion against her father, even raiding his larder to feed the poor and giving away his jeweled sword to, of all people, the local leper.

Dubtach knew the young beauty would be a prize bride and pointedly ignored her vow of perpetual chastity. He presented her with two suitors, one a king and the other a poet – in short, one rich and the other, arty. She flatly turned both down and was forced to make a most fervent prayer. She asked God to make her ugly, the better to focus on her destiny. Her prayers were answered when, the following morning, she awoke to discover she was the fifth-century version of the Elephant Man. The suitors hastily withdrew, but once consecrated a nun, Brigid, as the saying goes, got her looks back.

She now began her mission, first taking the veil, and once again aggressive angels appeared, this time to shove the priest aside and place the veil on her head. Then Brigid, with seven like-minded young friends, formed Ireland’s first religious community of women. Before Brigid, girls who took holy vows could only retreat to the family cottage and just… pray. But Brigid and her sisters did more than pray – they built, especially after the saint, using some sly magic involving her cloak, duped a local king out of 12 square miles of early real estate.

Under an oak, the sacred tree of the druids and on the site of a Celtic shrine, Brigid founded her monastery at Kildare (Irish: Cill Dara, “church of the oak.”) It was a “double monastery,” allowing both monks and nuns; she also accepted poets, artists, farmers, and craftsmen. Brigid’s monastery at Kildare was a happy place, a stark contrast to the Abbey of Glendalough, a reflection of its odd founder, Saint Kevin. Kevin prayed, standing, arms extended, a stance he maintained for seven years and, in winter, he recited his prayers, naked, in a freezing lake.

It could be claimed that Brigid laid down the foundation for Ireland’s legendary hospitality. Travelers and vagabonds, sick or well, Christian or not, flocked to Kildare knowing the inclusive Abbess would invite them to eat, drink, and stay as long as needed. She was all about largesse and compassion, as evidenced by her most famous poem:

I should like a great lake of finest ale for the King of kings.

I should like a table of the choicest food for the family of heaven.

Let the ale be made from the fruits of faith and the food be forgiving love.

I should welcome the poor to my feast, for they are God’s children.

I should welcome the sick to my feast, for they are God’s joy.

She only left Kildare to chariot through Ireland supervising the building of churches, schools, and convents, the latter to assure women received an education, something unheard of at that time. An artist herself, she established a school of art most famously responsible for the Book of Kildare, which was destroyed by Cromwell but described as “more gorgeously illuminated” than the Book of Kells.

Despite all her accomplishments, her legend grew because of her many miracles, so resonant with Irish mysticism: she taught a fox to dance, tamed a wild boar, hung her damp cloak (that cloak again!) on a sunbeam to dry, obliging the sunbeam to remain all night. In her later years, her powers took on almost Christ-like proportions – she could multiply food, exorcise demons with a casual sign of the cross, and calm storms. Proving she was someone you’d like to have a beer with, Brigid, fond of the brew herself, could produce bottomless barrels and turn both milk and water into ale. Once, while curing lepers, she learned there was nothing to drink and used her own bathwater to stand the entire colony to a pint.

Brigid was so revered in her lifetime that Saint Mel ordained her a bishop, although some (cranky) scholars may dispute this. What is not disputed is that she said mass, heard confessions and ordained clergy. And, yes, she was finally, after a long search, reunited with her long-suffering mother who had remained a slave all those years. The illustrious Brigid bought her mother’s freedom and took her to live with her in Kildare.

Brigid died in 524 and her cult quickly spread as her manuscripts were translated into French, English, and German and countless churches were named after her. She was buried in Downpatrick, County Down, with the two other major saints of Ireland, Patrick and Columcille. In the 17th century, British troops looted her grave, but Irish knights managed to deliver her head to Portugal while her busy cloak still survives in Belgium.

As befitting a woman as generous as Brigid, she has an extraordinary number of patronages: Ireland, New Zealand, Australia, newborns, healers, milkmaids, milkmen, poets, blacksmiths, boatmen, fugitives, nuns, printing pressers, barnyard animals, children whose parents are not married, seamen, and poultry raisers.

While explaining Christ’s death to a dying pagan, she wove a cross from the rushes strewn about his floor. Today, anyone with any sense, Catholic or not, Christian or not, Irish or not, can place them in their houses to ward off evil. It works and so do Brigid’s medals, available at the Franciscan Sister’s Gift Shop: (845) 424-3809 or giftshop@graymoor.org.

Bríd agus Muire dhuit! ♦

2024 commemorates 1500 years since the passing of St. Brigid. To recognize the occasion a week of culturally rich events is planned from January 27, 2024 – February 6, 2024, in County Kildare where St. Brigid spent much of her life.

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor/ reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info/ entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co-writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

The anonymous donor of the $20 million to St. Brigid’s is said to be a protestant. Architect Keely who designed St. Brigid’s Church reminds one of Kilkenny native James Hoban who designed the Presidential residence in D.C., which was burned by the British in 1812, and its reconstruction was supervised by Hoban, and painted white. Sine then it has been known as the White House. designed

Sweden also has a saint named Bridget (1303-1373). This noble holy woman married in her early teens and had 6 children before her husband died

If she was immediately sold off to a rival chieftain as a baby why do we continue to hear of her in her father’s house?

I think you misread it slightly. Her mother Brocseach was immediately sold, not Brigid.

The title of this article suggests that St. Bridget is known as Mary of the Gaels, Mary being the Blessed Mother. The apparition of the Blessed Mother at Knock in the 1870s is well known. However, few Irish people seem to have heard of the Weeping Irish Madonna of Gyor Cathedral, Hungary. This Irish icon was taken to the continent by Bishop Lynch before Cromwell’s invasion. During early morning mass at that cathedral on 17 March, 1697, soon after the Treaty of Limerick was broken by the English, the Irish Madonna shed tears of blood for about 2 hours. When the tears started, word quickly spread throughout the city, and a Calvinist minister, a Lutheran minister and a Jewish rabbi witnessed the event.

Interesting to learn of.

Any other instances of the Irish Madonna shedding tears in Ireland?

thanks for much for sharing this, and thank everybody, quite a lot of good information on here and I love this article. ! Blessings .

I enjoyed reading this account of Saint Brigid much more than the Wikipedia version that speaks of her poking her own eye and cursing a man to have his own eyes burst in his head. I am intrigued and would love a man audio book suggestion to learn more about Brigid.

There’s also a story of her changing water to mead at a feast.

Someone complained about the mead, and she changed it back to water. It does not pay to offend Irishwomen. I believe she’s also one of the patron saints of brewers (certainly, of meadmakers).

Magistarofnight2018@gmail.com

Miss ashu, 39*4/4/1979,nonworking,eye ear defect

Opp baba nachattar darbar, barnhara Road Ludhiana India

Mother brainstrokes 1944 father cancer

+919779875322, +919877424608

I really enjoyed this document I have to write a part on my fav st. so I chose st. Brigid and this website gave me a little more insight about her virtues and an inside look on her life. Thanks to all who commented and clarified things

Thanks for this great article. Her cross hangs over our entrance door in West Texas. I’ve gone to her in the past for help, and this fine piece gives me permission, even if I don’t need it, to go back. St. Brigid, indeed: Help us in our hour of need.

We, and all our children have St. Brigid crosses above our front doors.

Great article, told with a sense of humor which surely Brigid had!