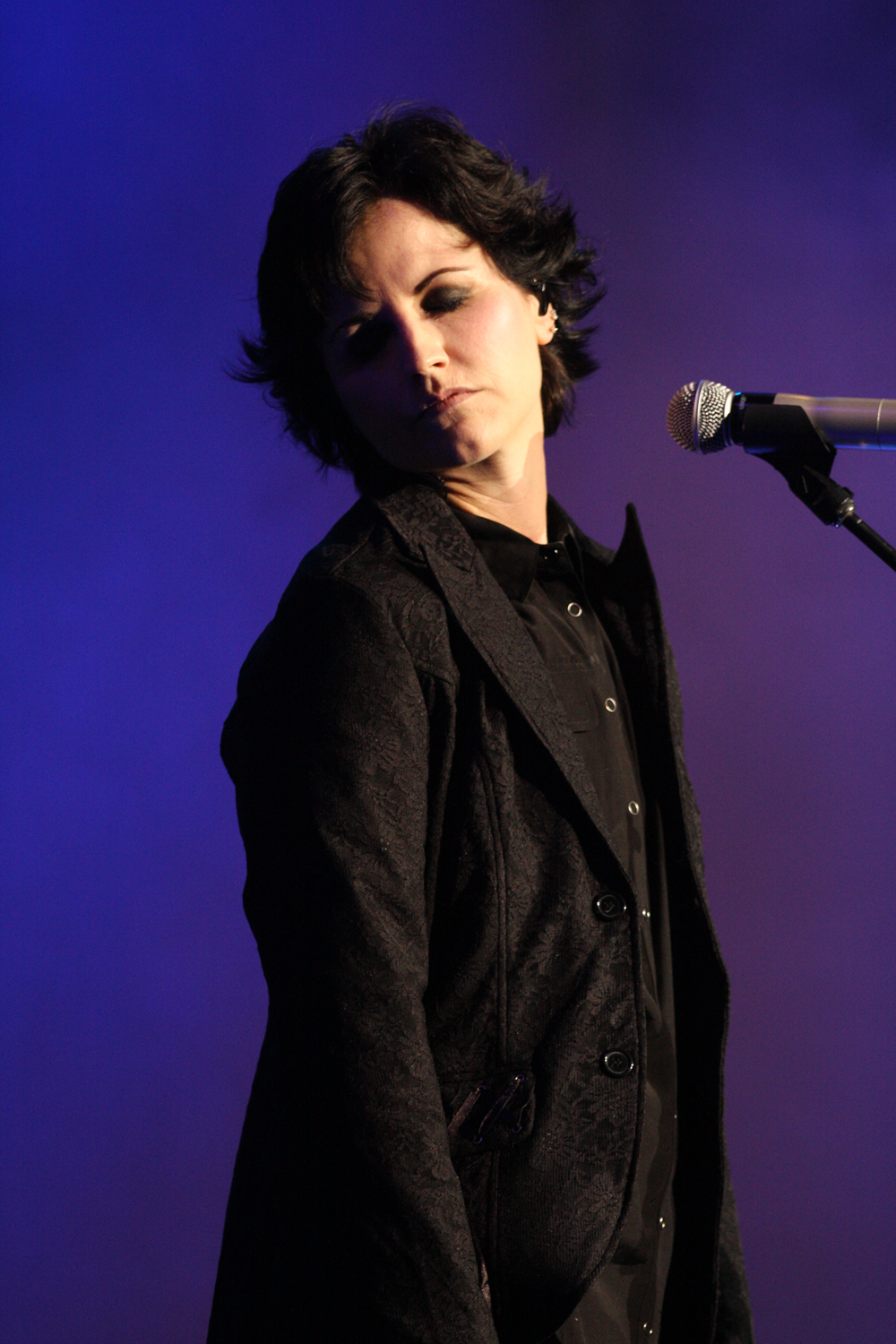

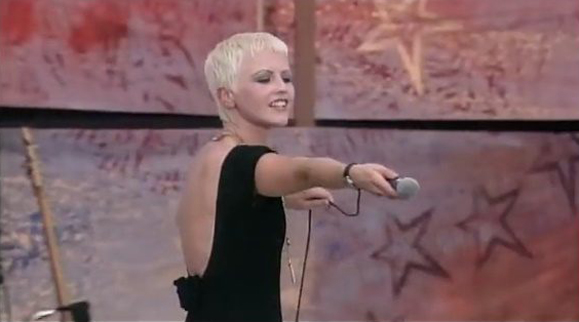

I WAS LEAVING the beer tent within yards of the main stage when The Cranberries came on. It was June 1994 and the band’s song “Linger” was a huge hit in the U.K., though I hadn’t heard of them when I bought my ticket for the Fleadh, an Irish music festival at Finsbury Park in London. For the past several hours I’d been soaking up the music of musicians I loved – the Saw Doctors, Christy Moore, Shane MacGowan. For a 23-year-old American girl who enthusiastically embraced her Irish heritage, things couldn’t get much better. So I whooped and cheered along with the crowd as Dolores O’Riordan rolled out in a wheelchair, her leg in a cast from recent surgery, guitar in her lap.

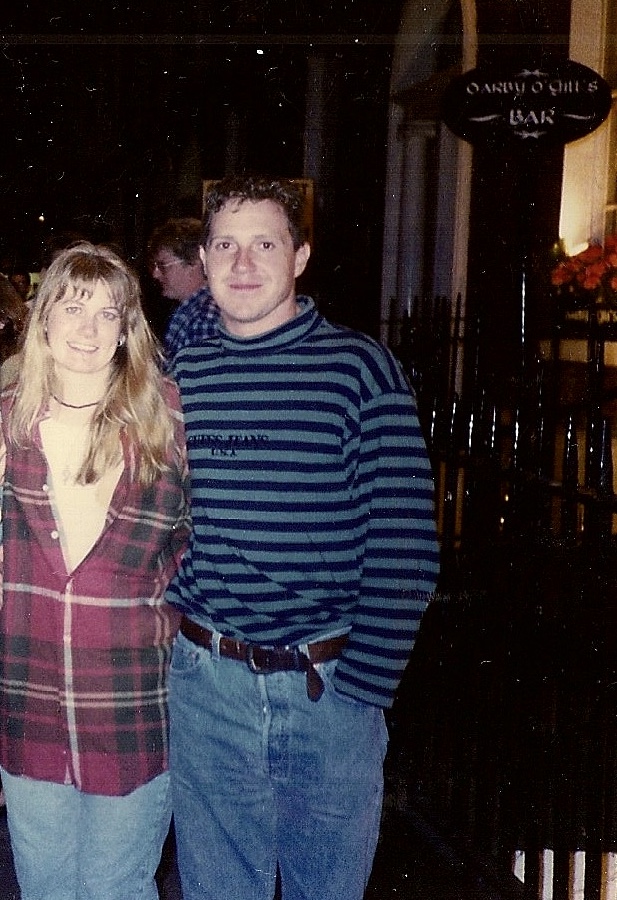

As she began to sing, a good-looking Irish guy emerged from the beer tent. His name was Colin and I’d met him in a mutual friend’s kitchen that morning, before we all set off for the festival. He walked over and stood next to me.

The Cranberries played eleven songs that day. “Put Me Down.” “Ode to My Family.” “Sunday.” O’Riordan’s plaintive voice sank low and then soared above us. Colin sang along, unselfconsciously. I gazed at his freckled arms and the strip of leather with a small blue cross hanging around his neck.

“They’re from Limerick,” he told me, shouting over the noise of the crowd. “Did you know that?”

I hadn’t known that. Earlier that day, within minutes of our meeting, Colin had told me that he was from Limerick City. The next time I was in Ireland, he’d said, I should come visit and he’d show me around. I’d said sure, oh yeah, that would be great, definitely. I was familiar with Mayo, Donegal, Galway, even Dublin, but Limerick – a word constructed of short, sharp syllables – was an unknown. I pictured a quaint town, perhaps a single narrow street lined with shops and pubs.

“Linger.” “I Can’t Be With You.” Colin and I stood closer together. His arm brushed mine. When the crush of bodies grew too stifling, he shoved them back, giving us breathing room. I hoped he’d put his arm around my shoulders.

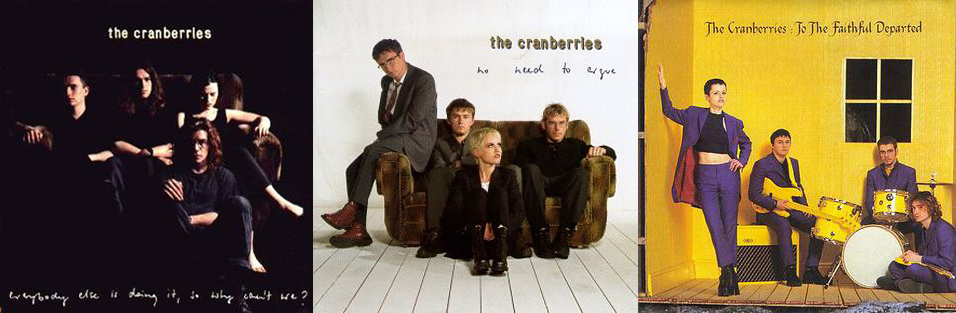

“How.” “Dreaming My Dreams.” “No Need to Argue.” After an hour, the set ended. O’Riordan smiled at the young, mostly Irish audience. Ecstatic, everyone hollered and applauded, having long ago risen from their seats on the grass to dance and sing. It was said The Cranberries were biggest thing to come out of Ireland since U2, and we basked in their display of ferocious Irish talent. Feckin’ brilliant.

We joined the stream of concertgoers leaving the park. As one of our friends tried to flag down a cab, I mustered my courage and pulled Colin aside. “Do you have a girlfriend?”

“No,” he said, a smile in his voice.

“That’s good,” I said, and kissed him.

℘℘℘

LIMERICK, when I did end up visiting a few months after meeting Colin, was bigger, busier, and much less quaint than I’d imagined. Colin took me to a pub in town. We walked past a fast food place on O’Connell Street, the main drag, called Supermac’s. A burly man stood inside the door. “Is that a bouncer?” I asked. “You have bouncers in your fast food restaurants?” I was from the Bronx and thought I was streetwise, but had never been in a McDonald’s with a bouncer.

Colin shrugged. “Yeah, for when the nightclubs let out.”

Later, I read that Dolores O’Riordan and the band’s manager had met up outside Supermac’s shortly before she joined The Cranberries. Such an ordinary place. I imagined her, a slight figure standing on the corner of O’Connell Street, soon to be a megastar, but for the moment just a shy Limerick girl with an astounding voice that could veer from a tender croon to a full-throated wail and back again.

℘℘℘

FOR TWO YEARS, Colin and I traveled back and forth to see each other, depending on where either of us was currently working. Edinburgh, Frankfurt, Limerick, Southend-on-Sea, New York.

The Cranberries’ third album, To the Faithful Departed, was released in April 1996. O’Riordan’s voice was everywhere you went. The album had a harsher, darker sound, but I loved “Salvation,” about drug abuse, and “When You’re Gone,” an ode to a lover. In May of that year, I moved from New York to Ireland so Colin and I could finally be near each other, and have a normal relationship. I envisioned us camping out at music festivals like the Fleadh, maybe taking a ferry for a weekend in France.

But three weeks after relocating to Ireland, I took a pregnancy test. It came back positive. Colin and I moved into a small flat on Davis Street, near the Limerick train station. We had little money for music festivals. Almost every day, I walked down O’Connell Street past Supermac’s. Limerick wasn’t the most picturesque place in Ireland. Not the friendliest or most charming. But strangers on the bus will compliment your baby; passers-by will help you lug the baby’s stroller up the stairs to the bank. The longer I lived in the city, the more I understood why the natives were so proud of the band that was formed there. Everyone knew someone who went to school at Laurel Hill with Dolores.

℘℘℘

ON SUNDAY, I checked the news app on my phone. Dolores O’Riordan, dead at 46. Forty-six? A year younger than I am, a year older than Colin. In Finsbury Park that day, she was only 22 years old. Obituaries report that her talent bore not only accolades but also demands, expectations, and critiques. At one point she struggled with an eating disorder. She worked and toured constantly. At the pinnacle of her fame, in the space of time during which I gave birth to two children, she had three. Back pain prevented her from performing for stretches of time. With the passing of the 1990s, The Cranberries receded from view. I hope she preferred it that way.

These days, when my daughter attends music festivals, she takes photos of herself and her friends, and posts videos of her favorite bands’ performances. The photos enable her to review the experience in all its detail at the touch of a button. But I wonder if something is lost when the past is so easily proven, when evidence is always in hand. Does a song on the radio carry the same enchantment? “Linger” will always spur memories of watching O’Riordan sing from a wheelchair, her powerful, beautiful voice a frame around me and the young man for whom I would move to Ireland, with whom I would build a life. I don’t know what I was wearing, can’t scroll through photos of my younger self. I don’t mind. Blurry memories are no less sweet than sharp ones. ♦

_______________

Cecilia Donohoe is a graduate of the CUNY Hunter College M.F.A. program in creative nonfiction. Her work has appeared previously in Irish America and The Best of Vine Leaves literary journal. She recently completed a residency at the Cill Rialaig Project artists’ colony in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry. Contact her at cecilia.donohoe@gmail.com.

I love it. Who knew we were in the presence of pure genius in Cill rialaig there a few months ago. Write on girl

That was great. Love it

Touching recount of a great singer and a great couple!