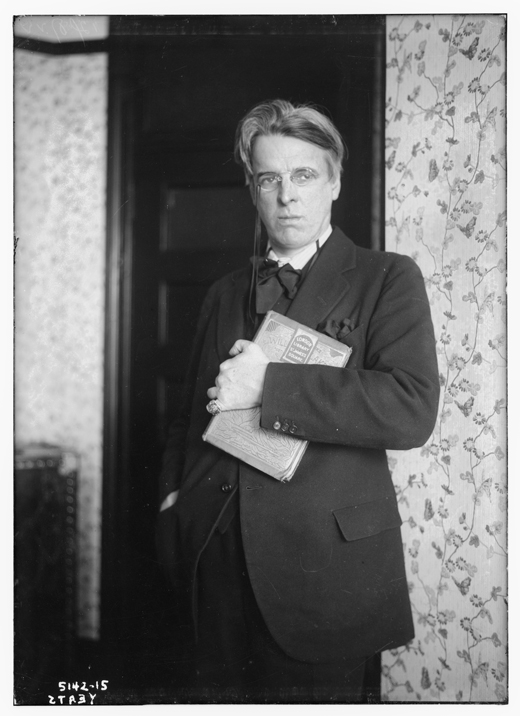

The story of W.B. Yeats’s tower, Lady Gregory’s autograph tree, and the grave of Irish airman Robert Gregory, whose death inspired some of Yeats’s most well-known poems.

January 23, 2018, marked the 100th anniversary of the death in Italy of Ireland’s most famous aviator, Major Robert Gregory. His grave stands in a quiet corner of Padua’s elaborate Cimitero Maggiore in a well-maintained section distinguished by its symmetry and simplicity. Twenty-five Commonwealth casualties of World War I are buried in this section, their white tablet headstones set in two rows. From behind, a white stone cross reaches 15 feet up, with a metal sword set on its front and those all-too familiar words, “Their Name Liveth Forevermore,” carved into its base. A box hedge surrounds the plot, and a row of mature thuja trees stands opposite, shading a bench where visitors can reflect on the consequences of the Great War or pay their respects to those interred here. Gregory’s grave stands at the far right of the first row.

The balanced order of the plot reminded me of the balanced order in “An Irish Airman Foresees his Death,” the poem in which William Butler Yeats gave lasting voice to Robert Gregory. Symmetrically divided into two equal parts by its two periods, the halves are themselves divided into two stanza-like quarters, each four lines long, each rhyming a-b-a-b, and each containing numerous antitheses. All work together to celebrate the “lonely impulse of delight,” the moment of balanced stillness that ends the poem.

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan’s poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

Soon after I recited this poem at Gregory’s grave, I heard above me the sound of a single-engine propeller plane, as if to remind me of what flight used to be. Gregory’s grave used to be different, too. It was originally marked by a wooden Celtic cross. Now, on the white headstone, the circle of that cross has evolved into the round crest of the Royal Flying Corps, with a crown at its top and the wings of an eagle breaking its circumference engraving: “Per ardua ad astra” (Through struggles to the stars). The Roman arms of the Celtic cross remain. Below them appear the words:

Only Child of Late Rt. Hon.

Sir W.H. Gregory K.C.M.G.

Of Coole Park Co. Galway

No mention is made of Gregory’s mother. Yet without her influence, Robert would be unknown today and two elegiac masterpieces by a Nobel laureate would not exist. Throughout her life, Lady Gregory credited Yeats with inspiring her to become a creative writer and giving her both a “means of expression” and “faith in myself.” She did not hesitate to inspire Yeats, in turn, to memorialize her son. When she informed him of Robert’s death, she urged: “write something down that we may keep.”

Lady Gregory was born Isabella Augusta Persse on March 15, 1852 at Roxborough House, seat of the wealthy and staunchly Protestant Persse family. The 12th of 16 children, she demonstrated from an early age not only an independent frame of mind, which soon enabled her to overcome the biases of her Ascendancy-class background, but also a practical sense of ambition, which eventually put her at the center of Ireland’s 20th-century literary revival. In childhood, Augusta showed an interest in romantic literature, particularly in the stories of mythical Irish heroes told by a nationalist nurse serving her unionist family. In her 20s, she gained invaluable experience managing Roxborough House and the estate for her brothers, 25 miles southeast of Galway, near the parish of Kiltartan.

By the age of 27, however, Augusta’s prospects for marriage were dimming. Then she met Sir William Gregory, whose estate at Coole stood only six miles away. A widower, 35 years her senior, he had recently retired from his position as Governor of Ceylon, previously having served twice in the British House of Commons, first as Conservative M.P. for Dublin and then on a liberal-conservative platform for County Galway. Knighted in 1875 (thus the K.C.M.G. on his son’s headstone – Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George), the politically imperialist Sir William was attracted to Augusta’s literary interests as well as to her management skills. They were married in 1880, and the following year their only child, Robert, was born.

Throughout the 12 years of their marriage, the couple spent most of their time in London or abroad. After Sir William’s death in March 1892, however, Lady Gregory began to spend more time at Coole, which her husband’s will had left her to manage in trust for Robert, until he turned 21. In the challenging economic and political circumstances of the time (with land agitation and the struggle for Home Rule), this was no easy task. Coole was not a wealthy estate. While Lady Gregory had to pay off debts, government measures required her to sell off lands to her tenants, thus reducing her income by half within 15 years.

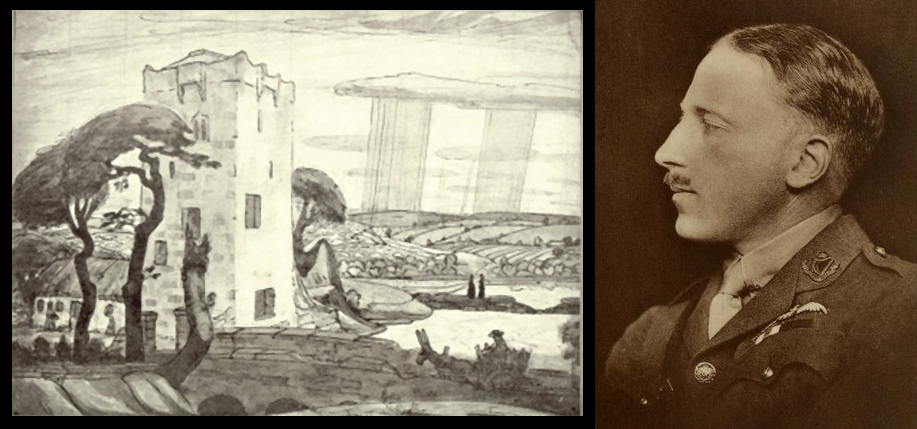

The Gregory lands included a 16th century Norman tower-house or castle keep, which had first caught the romantic imagination of William Butler Yeats in the last years of the 19th century. By then he had begun to spend his summers at Coole, initially collaborating with Lady Gregory on a collection of Irish folklore and fairy tales, then developing with her the idea of a national theatre, which would eventually become the Abbey, in Dublin. Yeats described his find as “the old square castle, Ballylee, inhabited by a farmer and his wife, and a cottage where their daughter and son-in-law live, and a little mill with an old miller, and old ash-trees throwing green shadows upon a little river and great stepping stones.” In 1915, Lady Gregory suggested that he buy the tower, since the tenants now wanted just the land. Yeats feared it would prove too impractical for a 50-year-old bachelor.

A year later, the abandoned tower having passed into the hands of the Congested Districts Board, Yeats nevertheless began negotiating to buy it. Another year later, confident that his intention to marry would soon be fulfilled, he purchased the tower (now in heavy disrepair), along with its attached cottage and a surrounding acre of land, for the price of only £35. The cost of restoring it would prove to be considerably more. A roof had to be added, floors rebuilt, windows and frames replaced, and the cottage expanded. Having married Georgie Hyde-Lees during the interim (in October 1917), Yeats and his now-pregnant wife moved into the cottage in September 1918, while the tower continued to be restored. This would be, intermittently, the family’s summer home for the next 10 years. To announce their acquisition, Yeats reproduced as a postcard Robert Gregory’s drawing of the tower and its landscape.

To approach “Thoor Ballylee” today (as Yeats renamed it in 1922) is to enter not only the scene that Robert drew, but also the setting that Yeats presented in his 12-stanza elegy, “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory:”

For all things the delighted eye now sees

Were loved by him; the old storm-broken trees

That cast their shadows upon road and bridge;

The tower set on the stream’s edge;

The ford where drinking cattle make a stir

Nightly, and startled by that sound

The water-hen must change her ground;

He might have been your heartiest welcomer.

Entering through the thatched cottage, I am struck first by a sharp smell from the fireplace just inside: “a fire of turf in th’ancient tower” invoking the third line of “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory.” Here I meet Rena McAllen, who manages Thoor Ballylee (with a small team of volunteers and one paid employee) for about 4,000 visitors each season, from June through September. Soon after she welcomes me with a cup of tea brewed in the cottage’s kitchen, I realize that her local knowledge matches her energetic hospitality. Born and raised only a mile away, Rena guides me through Thoor Ballylee with as many references to its history during her lifetime as during Yeats’s residence. Not to be missed is the 12-minute video written by the late Yeats scholar, Augustine Martin. Featuring archival footage, it sets Thoor Ballylee in historical context, reaching not only back to the Norman invasion of Ireland, but also out to the political troubles during Yeats’s time here.

Still, the highlight of Rena’s tour is the tower itself, particularly its “narrow winding stair.” While “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory” includes the first references to both in Yeats’s poetry, The Tower (published in 1928) would become the title of what is generally considered his greatest volume of poems, followed by The Winding Stair (published in 1933). Embedded in a wall seven-feet thick, the circular stair connects the tower’s four floors, each with a single room and a window overlooking the river. While the ground floor served as the family’s dining room, Yeats also wrote on its “great trestle table,” which his wife Georgie kept covered with wildflowers. In a letter to his father, Yeats called this the “pleasantest room I have yet seen, a great wide window opening over the river and round arched door leading to the thatched hall.”

The second floor, featuring a hooded fireplace and vaulted ceiling, served as the family’s living room, the third floor as Yeats’ and his wife’s bedroom. The fourth floor, the “strangers’ room” (where the couple may have intended to hold séances, in line with their occult interests) was never finished. A vent in the wall now houses 24 lesser horseshoe bats (a protected species, with only 600 remaining in Ireland). Similarly, a slit window off the winding stair contains a rook’s nest, reminding visitors of “The Stare’s Nest by My Window,” the penultimate section in Yeats’s “Meditations in Time of Civil War.” A final steep flight of stairs from the strangers’ room leads to the battlements, where Yeats would occasionally retire into the shadow of the large chimney, to escape horse-flies.

The walls throughout the tower remain unadorned, as they were in Yeats’s time, because the dampness sweating through the limestone would have damaged anything hung there. Reproductions of the original – furniture have been appropriately placed – the bed, the trestle table, a writing desk, a dozen three-legged chairs—and great brass candlesticks still flank the fireplace. Its hood has once again been painted black and gold, the surrounding walls deep blue. Together, the rich colors and heavy furniture enhance the medieval aspect of the tower’s stern simplicity. “It’s deliberately kept simple,” says Rena, identifying what she values most about the tower. Quoting “Blood and the Moon,” she explains: “I just love the fact that so little at Thoor Ballylee has changed, that you can still climb ‘this winding, gyring, grinding treadmill of a stair’ that Yeats walked up.”

Thoor Ballylee figures prominently in, and hovers symbolically over, “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory.” But what about Gregory himself, who doesn’t enter until the sixth stanza, as “my dear friend’s dear son”? In the next three stanzas, Yeats repeats the line, “Soldier, scholar, horseman he,” ultimately following it with, “As ’twere all life’s epitome.” Gregory was indeed a scholar, having attended Harrow School per family tradition, from 1895 to 1899, before matriculating at New College, Oxford University. Gregory was a horseman, too, an intrepid point-to-point jockey famous locally for adventures mentioned in the eighth stanza of Yeats’s elegy: “At Mooneen he had leaped a place / So perilous that half the astonished meet / Had shut their eyes; and where was it / He rode a race without a bit?”

About the “Soldier,” however, Yeats has little to say, though Gregory embraced that role early in the Great War. At age 36 (and with three young children) he was officially too old to fly, but he would nevertheless win membership in the French Legion d’Honneur as well as the English Military Cross. Still, Yeats resisted even Lady Gregory’s “suggested eloquence about aero planes ‘& the blue Italian sky.’” Instead, he chose to portray Robert primarily as an artist.

We dreamed that a great painter had been born

To cold Clare rock and Galway rock and thorn,

To that stern colour and that delicate line

That are our secret discipline

Wherein the gazing heart doubles her might.

Gregory was an accomplished painter, too. By 1902 he had left Oxford to study at the Slade School of Art in London, where he met the fellow art student he would marry, Margaret Parry. The two then lived much of the time in Paris, or traveled abroad, in order to paint. Yeats admired Robert’s work so much that he asked him to design sets both for his mother’s plays and for his own at the Abbey Theatre.

There was, however, considerable tension between the two men. Robert grew ever more resentful of the long periods of time that Yeats spent at Coole as Lady Gregory’s guest, where he occupied the master’s bedroom and had come to expect service. Though Robert had inherited the estate when he came of age in 1902, his father’s will had granted Lady Gregory residence throughout her lifetime. As for Yeats, he found Robert Gregory aimless and unreliable, showing little interest in the management of Coole and often failing to meet deadlines for his theatre sets.

None of this personal tension makes its way into “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory.” The poem’s chief tension consists instead of the opposed demands that the active life and the contemplative life present for any artist, Yeats as well as Gregory.

Ultimately, Gregory devoted himself to a military cause, Yeats to a poet’s “secret discipline.” Looking back over Robert’s short life, Yeats eulogizes him as a fire of “dried straw,” commenting: “and if we turn about / the bare chimney is gone black out / Because the work had finished in that flare.” The work would go for another twenty years for Yeats, until his own death at age 73. Lady Gregory suggested to him that for Robert, this poem would become “his monument – all that remains.” For Yeats, on the other hand, Thoor Ballylee would become (in his own words) “a fitting monument and symbol,” with all the wealth of reference that a great symbol provides: the artist in isolation, the mystery of romance, the resonance of history, the tradition of a cultured aristocracy, and, more personally, the proximity of that friend, Lady Gregory, “who has been to me for nearly forty years my strength and my conscience.”

Three-quarters of the way from Thoor Ballylee to Coole Park lies Kiltartan Cross, the crossroads identified as Robert Gregory’s “country” in “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death.” Here stands the attractive Kiltartan Gregory Museum, built as a two-room schoolhouse in 1892 at the behest of Sir William Gregory and designed by the architect Frank Persse, Lady Gregory’s brother. Beautifully restored in the mid-1990s, its grey limestone walls with red-brick trim and open arcade now preserve both a historic classroom and a collection of artifacts associated with Lady Gregory. Of particular note is an illuminated address, hand-painted on parchment, in which the Gregory tenants welcome Robert as their future landlord on the occasion of his 21st birthday. Lady Gregory later wrote about this “gathering of cousins,” with “the big feast and dance of the tenants.” Reflecting on the tumultuous 30 years that followed, she poignantly added (near the end of her life): “But the days of landed gentry have passed. It is better so. Yet I wish some one of our own blood would after my death care enough for what has been a home for so long, to keep it open.” The collection at Gregory Kiltartan Museum also contains photographs of what she never saw: Coole House being pulled down in 1942, for building materials, its contents having been auctioned off in 1932, shortly after her death.

Only the vestiges of the Gregory estate now remain. In accordance with the two-sentence will that Robert wrote in the train on his way to war, “everything I have” passed to his wife at his death.

Margaret’s efforts to sell Coole began within just a few years, but they did not reach a conclusion until 1927, when the house and its surrounding land of seven woods were purchased by the Forestry Commission. The sale gave Lady Gregory the right to live there until her death, at the cost of £100 per year.

Today, the demesne comprises a thousand acres of woods, river, turloughs (dry lakes), and bare limestone in the Coole / Garryland Nature Reserve. Trails provide access to the landscape that inspired not only Lady Gregory, Robert Gregory, and W. B. Yeats, but also his brother, the painter Jack B. Yeats. Here, too, visited the painter Augustus John and so many writers in the Irish Literary Revival of the early 20th century: George Bernard Shaw, J.M. Synge, George Russell (Æ), George Moore, Douglas Hyde, and Sean O’Casey. What were the stables and barn have now been converted into a visitor center. Be sure to purchase here Colin Smythe’s excellent A Guide to Coole Park. In addition to its informative text, it contains reproductions of paintings and drawings by Robert Gregory, Margaret Gregory, and Jack B. Yeats, as well as photographs of Lady Gregory, her house and estate, and her many literary visitors. Also, be sure to watch here the equally excellent 30-minute video, Lady Gregory of Coole, which surveys her life, relationships, and accomplishments.

Still, the highlight of the visitor center is its permanent exhibit, based on the charming memoir Me & Nu, written by Lady Gregory’s granddaughter, Anne, about the time that she and her sister, Catherine, (nicknamed Nu) spent as children at Coole. The exhibit presents the rooms of the house (nursery, library, drawing room) from the children’s point of view. Especially interesting is the audio-visual material: footage from Abbey Theatre productions, a film clip of George Bernard Shaw commenting on Coole, and a recording of Yeats in “his humming voice” reciting his poem “For Anne Gregory,” in which he celebrates her “yellow hair.”

Outside, finally, in the walled garden stands a great copper beech known as the Autograph Tree. In 1898, Lady Gregory began a tradition by inviting Yeats to carve his initials into it. Thirty years later, she would remember: “And on the great stem, smooth as parchment… many a friend who stayed here has carved the letters of his name.” So too did her son. His are now aging into illegibility on the living tree, in a way that the “carven stone” of his grave in Padua’s Cimitero Maggiore never will. This time, however, his mother is rightly acknowledged, instead of his father. Lady Gregory carved her own A.G. into the “parchment” of the copper beech right above Robert’s W.R.G., which is carved just above Yeats’s W.B.Y. Here, we should pause to recite not “An Irish Airman Fore- sees His Death” or “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory,” but rather the conclusion to “Coole Park, 1929,” in which Yeats anticipated the results of his “most true” friend’s death:

Here, traveller, scholar, poet, take your stand

When all those rooms and passages are gone,

When nettles wave upon a shapeless mound

And saplings root among the broken stone,

And dedicate – eyes bent upon the ground,

Back turned upon the brightness of the sun

And all the sensuality of the shade –

A moment’s memory to that laurelled head. ♦

_______________

Philip Kokotailo is dean of faculty at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston, where he teaches English. The author of John Glassco’s Richer World: Memoirs of Montparnasse (ECW Press, 1988), he has a particular interest in the literature, art, and music of the early 20th century.

Editor’s Note: This article was published in the February / March 2018 edition of Irish America magazine.

Click here to hear a recording of W.B. Yeats as he introduces and reads his works “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” “The Fiddler of Dooney,” “The Song of the Old Mother,” and “Coole and Ballylee” – with, in his words, “great emphasis upon the rhythm.”

Thanks for this unique take on things.

Was struck whilst reading it how things were strung together about the Tower.

I was left reflecting then how much archetypal significance a la Tower was pressing in on us now, as say an astrologicak or other metaphysical commentary might speculate?

Wow, I never heard of any of this before. Trust you to find new and exciting news.

Very interesting, I visited the tower back in 1976 with some classmates from college.

Yeats’ poem ‘An Irish Airman Foresees His Death’ was the inspiration for a self-portrait in oils I did titled ‘Impulse’. As I was a pilot (with Aer Lingus) I drew regularly on overseas trips, and I thought often about Yeats’ poem about Robert Gregory. In ‘Impulse’ I insinuated myself into the scene wearing a leather pilot’s helmet that belongs to the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, whom I was visiting. In the background is Thoor Ballylee and Robert Gregory’s aeroplane, Yeats’ poems were also the inspiration for several other paintings, including Cap and Bells, The Departure of Oisín, Silver Trout, Penny, Brown Penny, and Heaven’s Embroidered Cloths. Thoor Ballylee near the Burren region is beautifully set beside the river and bridge, and well worth a visit.