William James Hinchey traveled throughout America’s Southwest frontier and Missouri capturing images of life, the ravages of war, and beyond.

Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian (1985) depicts the rough, perilous place that was the American Southwest of the 1840s and ’50s. One of the earliest close-up views of the California-Arizona desert of the period is provided by Thomas W. Sweeny’s diary of his time as a U.S. Army lieutenant assigned with his few men to the Gila-Colorado River area from 1849 to 1853. The diaries and drawings of another Irishman, the artist William James Hinchey, also provide significant glimpses of an area of the American frontier of the 1850s, one farther north from the border: Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the historic trail leading there. Over time, Hinchey would provide valuable images of life in St. Louis and southeastern Missouri through the Civil War and beyond, and in 1996 the National Frontier Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri, featured an exhibit titled “Scenes from the Road to Santa Fe: Sketches by William James Hinchey.”

Introducing a Hinchey exhibition at the St. Louis Art Museum in 1991, the museum’s assistant curator, Lynn Springer, noted that although Hinchey is famous for only one painting, his ten sketchbooks and extensive diaries provide an exceptional historical record. His St. Louis scenes, she said, “are not only works of art in themselves but they are historical documents from a period for which we have relatively little visual evidence.”i

The notable Hinchey painting to which Springer referred, now housed at the St. Louis Art Museum, is his iconic image of the 1874 dedication of the Eads Bridge, the 19th century American architectural and engineering marvel spanning the Mississippi River from the Illinois shore to St. Louis.

Hinchey came to find himself in the American West by a circuitous route. Though his future would lie in America, his first travels were in the direction one might expect of an Irish artist – to Paris, by way of London, for a period of study and sketching at the Louvre. His father had encouraged William’s artistic bent from its earliest manifestations. At eight, the boy had already sold his first work and by 12 was determined to be a portrait painter. “As a boy I was very successful in making pencil sketches of members of my family and friends,” Hinchey noted. “By the time I was 16 I was painting portraits in pastel and oil of many persons who came to me for that purpose; and I received good pay for my work.”

His father, Paul Hinchey, was in charge of the public buildings in Dublin. This exposed the boy to “a large force of mechanics, painters, carpenters, stonemasons, etcetera.” Among these artisans was a Mr. Egnore, who specialized in applying gold leaf to ornaments, frames, and various interior decorations of buildings, a skill William found appealing and at which he soon became competent. Indeed, he would always be something of the enterprising artisan/ artist, taking what work presented itself, including at times mere sign painting, and advertising himself as a portraitist very much for hire.

By the late 1840s, when Hinchey was ready to matriculate at Trinity College in Dublin, he had earned enough from portraiture to cover half his academic expenses and had cultivated skills that would later recommend him for work in Spanish mission restoration in the American southwest.

In 1850, when he was 20 and in England, he encountered Sir Isaac Pitman, creator of the Pitman shorthand system. Hinchey became fascinated with the method and was soon adept at it. This would result in his diaries in shorthand, which he kept diligently for 16 years of his life, covering his journey to New Mexico and continuing through the Civil War. They were not transcribed, though, until his son Stephen – having been taught Pitman by his father – did so in the 1950s; the only two manuscript copies belong to the State Historical Society of Missouri and the St. Louis Art Museum.

Hinchey’s ultimate departure from Ireland for England and the continent was not entirely his own idea; his Irish nationalist convictions and activities had rendered him persona non grata in Dublin. Based on what he recounted to his son, the activity that got him in trouble appears to have been partly political and partly a matter of youthful rowdiness. William ran with a boisterous gang of young men who roamed Dublin streets breaking the occasional window in a government building and being generally “rather loud in their denunciation of English control of Ireland.” The British government eventually began to keep a file on the group and, on an occasion when the boys had taken to the country and engaged in some land reform agitation on behalf of Irish tenant farmers, they were arrested and charged with conspiring against the Crown. Hinchey’s father, probably thanks to his government position, got word of the prosecution about to be launched against William and his cohorts and urged his son to flee Ireland right away. William did so, but his Irish nationalist convictions would endure – he would name one of his sons Robert Emmett Hinchey.

The Dublin family into which Hinchey was born in 1829 was a mixed one religiously. His mother, Mary Doyle Hinchey, was a devout Catholic. His father, an equally devout Protestant and grandson of an Episcopal rector in Limerick, wed Mary while harboring the idea that she would ultimately convert his way. She had similar illusions about her husband becoming Catholic, and the result was eight children double-baptized and taken secretly to mass without their father’s knowledge.

Indeed, it was a Catholic connection that would prompt Hinchey to take the critical step of leaving Paris and striking out for Santa Fe and the Spanish missions. Hinchey had met Jean-Baptiste Lamy, the Catholic Bishop of the Santa Fe diocese, in Paris in 1854. Lamy was sufficiently impressed with Hinchey’s artistic skills to offer him a papal contract to go to the New Mexican Territory, which the United States had acquired six years earlier, to work in mission restoration, inventorying artifacts, and as an artist in residence.

Lamy, on whom Willa Cather based the character Bishop Latour in her novel Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), had already spent some ten years in Ohio and Kentucky when Pius IX appointed him to the Santa Fe bishopric. Hinchey was not disinclined to undertake the adventure: “I had read much and dreamed of the glory of America…. It was not hard to persuade me into leaving for a year my position in Paris to indulge in such an excursion. The contrast between the Pinnacle of Art and refinement and the world of untamed savagery of the western wilds, far from daunting me, became the very charm of the enterprise.” He departed France on the cross-channel trip on July 30, 1854, in the company of the bishop and seven priests, bound for America by way of England. On August 2, 1854, the Bishop’s party departed Britain aboard the U.S. ship Union. Though he planned to return to Paris, Hinchey’s American odyssey would be more consequential than he anticipated and would define his career and personal life until his death in St. Louis at 64, almost 40 years later.

Hinchey’s diary entries regarding the Atlantic passage indicate his gregarious character. There is much circulating and meeting with people and entries such as: “This evening very fine. Singing and talking on board. Recited some of [Thomas Moore’s] “Lalla Rookh” for Mr. Rernend; on deck alone until one a.m.”

Following a 14-day sea voyage, Hinchey and the party arrived in New York and, after a brief stay, set out by train for Cincinnati. The travel accommodations in the U.S. at the time were crude, the railroads still rudimentary, and the journey was a far cry from the comfort of the Atlantic passage: “Having been traveling all the preceding night and this day we are still on the road, tearing, puffing, belching, and throwing fire, on we go, smothered with dust and ashes; occasionally stopping to snatch up a hasty meal by the way; and then hurrying to the train; again there to be jostled and tumbled for a few hundred miles more,” Hinchey wrote in his journal.

The company arrived in St. Louis on September 4, 1854, and Hinchey records stepping from the riverboat “very weary.” They had been defrauded of their food for breakfast on the Justice, he noted – a “dirty, stinking, little rat trap of a boat” – and there was to be no rest to speak of at St. Louis, merely a transfer of baggage to the Missouri River boat Polar Star bound for Independence, a departure point for the western trails, including the one to Santa Fe. The Polar Star proved “a very superior boat in every way,” its accommodations and comforts first-class and a great relief from the miseries of the Justice.

Independence was the farthest point westward on the Missouri River that steamboats could travel, and Hinchey describes a bustling, and sometimes hectic embarkation hub as western-bound parties hired guides and purchased horses, mules, wagons, food supplies, guns, and tents for the frontier, or found wagon trains to join. Besides illnesses, there were frequent injuries among pioneers less than familiar with guns and dealing with unfamiliar, newly-purchased animals. Recalcitrant horses, steers, and balky mules ran loose and would have to be repeatedly rounded up. Among other hardships, travelers soon discovered that tents and wagon covers would afford virtually no protection from the fierce rainstorms of the mid-continent. Later, on the trail, however, Hinchey would note with wonder how people could adapt to this difficulty – in the middle of the night, in a tremendous rainstorm, lightening would illuminate the camp momentarily and reveal people sleeping soundly in the soaking downpour.

On October 3, 1854, the Santa Fe-bound caravan set out on the rough road that would take them southwest across Kansas to the New Mexico Territory. They progressed to the Cimarron River through what Hinchey describes in his diary as “wretchedly bleak country,” – something reflected in his bleak, minimalist trail sketches. By November 10, they were at Fort Union – a military site where a doctor was available – 110 miles from their destination: “A great deal of snow all along, the train getting stuck several times in snow and mud. Breakfast in snow surrounded by hills covered with snow….”

On the 16th they came to Pecos, a tiny trail town on the approach to the capital. Exploring about a mile from their camp, Hinchey and another man entered an old building that proved to be an abandoned friary or monastery:

“Small apartment which must have served as a vestry stood between the western branch and the head of the cross… Where the grand altar must have stood there was a large space in the plastering, much in the form of a gothic window extending from roof to floor. Some fireplaces in the corners of the little rooms told how cozy the inmates must have felt at a cheerful wood fire when the wintry winds had howled through the snowy mountains some doleful Indian tale.”

It was November 18 when the wagon train reached the dreary adobe settlement that was Santa Fe in winter 1854. Despite the snow, the town had prepared its version of a gala welcome for the bishop’s return after a year’s absence – a military band marched and an honorary dinner was held. Hinchey found the town singularly unprepossessing, however: “All was new but nothing pleasing… Had not the whole affair been so novel to me I should have been as much disgusted as I am now as I write this a week later.” His mood was not helped by the death of Abbé Vaur, one of the party who had come all the way from France only to die on the night of his first day in Santa Fe. Hinchey’s diary entry suggests he felt the Abbé had been less than well-attended: “Dead without the sacraments! In a bishop’s house. A month sick, and snoring priests about him when he breathed his last!”

The former mining town of Santa Fe was not extensive in its expanse, and Hinchey, an habitual walker, had soon been around what there was of it – nothing left to do besides his church repairs, he remarks, but “to contemplate the great variety of characters in this small metropolis.” (Among them included frontiersman Kit Carson and the infamous Doña Tules, Santa Fe’s wealthy courtesan and gambling queen.) Adding yet further to Hinchey’s disappointment, however, he discovered that the adobe church walls in the area were not receptive to paint, which made executing frescoes nearly impossible.

He became increasingly aware of the plight of impoverished Mexicans in the town, now some seven years since the war. He records stopping by Owens’ Store and witnessing Mexicans without currency coming in to sell their last possessions. The store owner attended a little girl who “pledges a fine massive gold earring with a shield shape stone for five pounds of sugar. Such is business in this capital.” A few days later in the city’s main plaza he saw a Mexican man drop a coin and an Anglo carpenter snatch it before its owner could. The Mexican held out his hands and insisted it be returned, but the American slashed the out-stretched hands bloody with a saw he was carrying. This was too much for Hinchey’s 19th-century Irish sensibilities to tolerate, and he wrote a letter of protest to the Santa Fe Gazette describing what he had seen. His letter, published in the Gazette of February 24, 1855, concluded, “Are they to be treated as brutes unworthy of the least consideration… by their conquerors? ”

A diary entry on January 23, 1855 reads, “This evening I talked publically of my intention to return to the States by the first train,” and by the next day he noted he had made arrangements with the bishop for departure with the train of Vicar Joseph P. Machebeuf (future Bishop of Denver). On February 28, 1855, after three months in Santa Fe, Hinchey departed on horseback as a member of the vicar’s wagon train headed north and east. He was back on the trail, again sketching as he went. At journey’s end, approaching Independence, he wrote, “When I came in sight of it, it seemed to me as though the houses were all illuminated from within, so did they shine in my eyes after the miserable huts of Santa Fe.”

Contrary to his intention to continue on back to Europe, Hinchey, then 25, had soon made numerous friends in Independence and its environs, and he stayed on for a little over a year. Within a few days of his arrival, in fact, on April 12, he notes: “Placed an advertisement in newspaper as portrait painter.” His diary entries during this time indicate his ability to acquire large and small artistic commissions along with more mundane jobs such as painting store signs: “Today I worked on the sign for the Italian Confectionary store.” A January 1856 entry reads: “Finished the Hibernian Benevolent banner.” He was an habitual attendee at, and sometimes participant in, Lyceum lectures and debates, and it was in Independence that he became enamored with another popular feature of contemporary Americana – the preaching of itinerant evangelists, especially that of the Methodist W.M. Prottsman. On July 26, 1855 he noted, “I went to Camp meeting and joined the [Methodist] Church!” He continued his eclectic church attendance, however, noting here and there attendance at Baptist, Catholic, Presbyterian, Mormon, and other services, and noted in February 1856, “Heard about town that I was called a Catholic.”

In Independence he became infatuated with a young lady – Pensy Musgrove, from Lexington, Missouri, whom he encountered with her family at a fair in October 1855, and walked about with. He “was enchanted by her manners,” he wrote. The next day: “walked with her over the bluffs and was enraptured by her conversation… took her to church and home again. Felt myself falling in love. Left soon and suddenly, as the father came home and found us alone.” The romance did not thrive, despite Hinchey’s best efforts, and Miss Musgrove became engaged to a man she had been seeing before Hinchey came on the scene. On May 30, 1856, having heard of her impending marriage, he departed crestfallen: “paid my hotel bill, and then at night went aboard the F. X. Bray, and next morning early left for St. Louis.”

℘℘℘

St. Louis was then a city in which a traveling Irishman might feel somewhat at home. Its first newspaper, the Missouri Gazette, had been founded by Joseph Charless, an Irish immigrant, in 1808. Another immigrant, John Mullanphy, was the city’s first millionaire, and his son Bryan the city’s mayor from 1846 to ’47. When Anthony Trollope arrived in St. Louis a few years after Hinchey, he would comment on the city’s abundant Irish and German populations: “If I were to form an opinion of the language I heard in the streets of the town,” he observed, “I should say that nearly every man was either an Irishman or a German.”iii

In addition, St. Louis’s Catholic archbishop, Peter Richard Kenrick, was, like Hinchey, a Dubliner, and Hinchey would do a posthumous portrait of Kenrick’s brother Francis, the Bishop of Baltimore, some years later at the archbishop’s request. Portraiture remained Hinchey’s specialty and the means whereby he made his way financially, eventually supporting a family that by 1875 would include six children. The eminent St. Louis portraitist at the time was Manuel de Franca, however, whose acquaintance Hinchey made right after arriving in the city. De Franca was a major artist with a classical portrait practice, its clientele drawn from the city’s aristocracy, while Hinchey attracted more middle-class customers – his work was comparatively inexpensive, often making use of photographs and daguerreotypes. “De Franca’s friendship and patronage undoubtedly helped the young artist establish himself,” and, Springer notes, “it was not long before Hinchey had developed acquaintances that led to… commissions.”iv He became part of a St. Louis artistic community that included George Caleb Bingham, known for his paintings of the frontier.

The city must have seemed a comparatively sophisticated and promising municipality after his taste of the Santa Fe Trail and even Independence. The Missouri iron country, which would decline in importance after the turn of the century due to the discovery of richer deposits in the Lake Superior range, was burgeoning in the 1850s, notably in the Arcadia Valley, the region running south out of St. Louis some 80 miles to Iron Mountain and Pilot Knob, the area that would eventually capture Hinchey’s imagination and be his ground as artist from the age of 30 onward. He would become, in effect, a Missouri regionalist painter and an invaluable recorder, in visual and written terms, of the area’s life over more than three decades, including the darkly eventful years of the Civil War during which his war sketches and dispatches would appear in Harpers Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News, and the New York Illustrated.

Hinchey’s introduction to the Arcadia Valley came after a period of rooming in St. Louis at the Planter’s Hotel. He there met Jerome C. Berryman, a Methodist preacher and rector of an academy in Arcadia, who offered him a position as an instructor in art and French, and recommended the southeast Missouri area for its landscapes.

The small town held the architecturally impressive co-educational Methodist academy and an Ursuline convent as well, both of which locations Hinchey would eventually sketch. He accepted the teaching job in August of 1856 and remained at the school for a year, during which a romance developed with one of his students, Lucinda Jane Holloman. The Hollomans were a prominent family in Arcadia; Lucinda’s father was the presiding judge of Iron County and later a state legislator. The couple married in August of 1857 and moved to the picturesque port town of Alton, Illinois, just upriver from St. Louis on the Mississippi, which would allow William to commute to his St. Louis studio.

Sketches and diary notes from this period reveal his frequent travels from Alton to St. Louis and down into Iron County and back.

“Great talk of war,” is his diary entry penned at St. Louis on April 16, 1861, by which time he and his wife had resumed living in Arcadia. His war reference is not to a remote menace – southeast Missouri bordered the emerging Confederacy and flanked the strategic Mississippi River. The river was an immensely important waterway itself and additionally so for the numerous other major tributaries that flowed into it. St. Louis afforded an invaluable command of the river and its traffic and was home to a major federal arsenal complex occupying 56 acres on the river’s western bank. Making matters especially volatile in St. Louis as war approached, Missouri was home to a population split as to Union allegiance, and the governor, Claiborne Jackson, was a politician of ardent Southern sympathies with the power and inclination to muster and command a state guard outside Washington’s control. Thus hostilities broke out in St. Louis while the war clouds were still building over northern Virginia and Washington. Three months after Hinchey’s “great talk of war” diary notation, and a few weeks after Bull Run, the bloodiest battle ever fought on the North American continent up to that time occurred at Wilson’s Creek, near Springfield, Missouri.

Just before the outbreak of war in St. Louis, Hinchey sketched the encampment of the secessionist State Guard set up in Lindell Grove west of town. He was present as well for the confrontation at the camp on May 10, 1861, when federal troops captured the encampment of the governor’s guard, following which there was a riot in which 30 civilians were shot. The years of what Edmund Wilson would later call “patriotic gore” had commenced, and Hinchey, having been present at the war’s St. Louis debut, would follow and chronicle the Missouri war throughout its duration.

After the Union Army gained the upper hand in the state, the hostilities moved into a new phase, one more in the guerrilla mode and consequently of an unpredictable, restive, and capricious character, as Confederates would resort to raids into the state from across its southeast border. The atmosphere evoked in Hinchey’s diaries and other writing is the Missouri of martial law, rumors, and impromptu clashes as the major Civil War actions shifted to other theaters. The prosperous Holloman farm in Arcadia was assaulted by military troops. “Now commenced a series of troublesome days and watchful nights,” he wrote on August 25, 1861, “which seemed to promise no good end. Soldiers pilfer, steal, rob, insult and threaten.” His wife Lucinda’s father had been opposed to secession, Hinchey noted, but was considered a southern sympathizer since two of his sons were in the Confederate Army. Another diary entry in the same period noted that “the soldiers of both the Northern and the Southern armies have plundered the farms of every item of food which they could lay hands upon day and night. One of the Holloman family sons was wounded near Potosi, Missouri in early September of the war’s first year, only three days after leaving home. He died, Hinchey recorded, “two days after his sister Mary and I were allowed to get to him.”

Taking full advantage of his Irish (British) citizenship and his journalistic employment, Hinchey secured letters of passage from Army officials permitting him to move about the eastern half of the state. As a neutral, artist, and journalist, he was generally well-treated, he notes, and able to post sketches and written reports to national journals. Ever the entrepreneur, he recognized the modest opportunity conditions provided: “Today I adopted a plan of painting low-priced pictures in oil on paper for soldiers, particularly those just entering the service.”

By January of 1862, he had set up a studio in the parlor of his Arcadia home and continued his enterprise of painting oil portraits of soldiers on duty in the area, but by March he was recording that the portrait business was rather slack and the soldiers out of money. Weariness with the conflict may have set in by this point as well, the romanticism in uniformed portraits beginning to lose some of its original glamour. By May, at the recommendation of Army officers, he undertook a trip to Washington, D.C. to see about portrait demand in the capital. Avoiding the areas of strife that a direct journey through the Border States would have entailed, he traveled north from St. Louis to Chicago by train, then to Ft. Wayne, Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and finally the capital.

“The first incident I saw was two men fighting,” he recorded on his arrival in Washington, D.C. on May 15, 1862. He remained there for almost three months, at lodgings on Ninth St., until August 7, painting portraits and going about the city. He made it a point early on, on May 23, to attend a performance of Dion Boucicault’s extremely popular Irish melodrama The Colleen Bawn at the Grove Theatre. Later in his stay he met an old Dublin school-fellow, Michael O’Shaughnessy, with whom he went to hear the singing at St. Aloysius’ Church. But in the Washington area the wear of the war was evident by this time: “Saw a good many wounded soldiers returning from the battlefields after their unsuccessful attack on Richmond,” he recorded on June 4. In Baltimore on August 7, he noted, “great consternation, and crowds running away to Canada to escape draft.”

On his return to Missouri in August, conditions had not changed, and continued martial law wore on the population. Stopping at De Soto, near St. Louis, Hinchey found “the neighborhood as much excited as ever by the contentions of the natives and the armed Dutch [German] home guards. Raids of retaliation almost every night.” On May 28, 1863 he wrote, “The country is in a miserably wretched state. The people at the mercy of petty officers and thieving soldiers. And no prospect of improvement.” His notes move between the local war perspective and the national one: “The Southern Army of Virginia has entrenched and fortified itself at Fredericksburg…. The Irish brigade attempted to storm the heights, but was terribly slaughtered, and the whole Northern army is driven back across the Rappahannock.” So things went through the war years until 1864, when he gave up his diary-keeping, his final entry being August 6, 1864.

(In the epilogue to his transcription of his father’s diary, Hinchey’s son mentions his father’s illness in that year, which could be related to the diary cessation.)

After the war, the family, then including four children, moved to Carondelet and later to De Soto, both St. Louis suburbs, and Hinchey maintained a studio at Fifth and Olive streets in the city, from this point on living a quiet life compared to his adventurous younger years. 1874, however, saw great excitement in St. Louis as the Eads Bridge gracefully spanning the Mississippi River was completed – a technological wonder of the century and to this day a St. Louis landmark. The bridge’s dedication on the fourth of July, opening with a 100-gun salute, was spectacular. General William Tecumseh Sherman drove the last spike, and a parade fourteen miles long wound through the city. At dusk an enormous firework display burst forth. Hinchey painted the image of record of the event – a view from mid-river, the riverboats lined up facing the bridge, a blaze of light in the night sky.

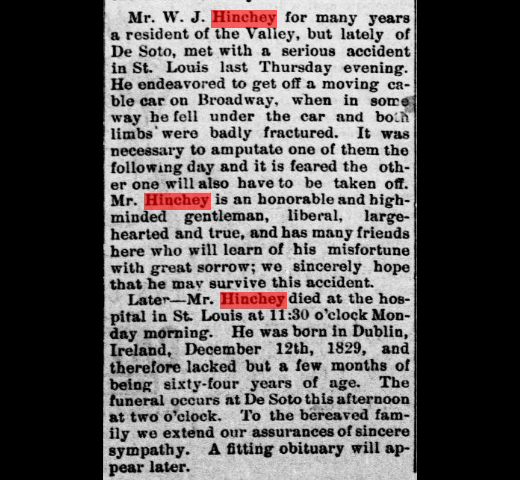

On September 7, 1893, the 64-year-old Hinchey fell from a St. Louis Railway car at Broadway and Poplar streets downtown. His legs were run over and his injuries so severe that an amputation of one leg was scheduled for the following day. A St. Louis Globe-Democrat reporter was present on September 9 when Hinchey was laid on the table in a City Hospital surgical room for the operation, and so were two of the artist’s sons whose faces the reporter described as “agonized.” As preparations were made to place the chloroform mask, Hinchey asked to say a few words, noting he might never get up from that table, which in effect he would not – he died within a few days of the surgery. He said he wished to thank Mr. Gladstone for his efforts on behalf of Irish Home Rule. “He is a noble man,” Hinchey affirmed, but added that Ireland’s freedom would have to be gained by Irishmen themselves. “I feel she will be free,” he said, “I know she will be free.”v ♦

_______________

Jack Morgan is emeritus research professor of English at Missouri University of Science and Technology. He is the editor of The Martyrdom of Maev and other Irish Stories by Harold Frederic (Catholic University of America Press, 2015), Joyce’s City: History, Politics and Life in Dubliners (U. of Missouri Press, 2015), New World Irish: One Hundred Years of Lives and Letters in American Culture (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2011), and other books and numerous journal articles. He lives in Winsted, CT.

_______________

Notes

i Lynn E. Springer, The Rediscovered Work of William J. Hinchey (St. Louis: St. Louis Art Museum, 1974). Introduced by Katherine Hinchey Cochran, the artist’s granddaughter.

ii The present article is drawn from the Missouri Historical Society manuscript.

iii Anthony Trollope, North America, Vol.2 (New York: St. Martin’s, 1986) 81-82.

iv Springer, 14.

v St. Louis Globe-Democrat. September 9, 1893.

I enjoyed reading your story very much. I’ve done a lot of research on the Hinchey family, and currently live in the house in De Soto they built in 1891. If you have other Hinchey stories, please let me know. I have some items you might find interesting.

Recently a painting of the Cresswell farm in Washington Co. was donated to the St. Louis Art Museum and is on display.

Because of its location I’m suspicious that it was painted by Hinchey..

I am looking for samples of his portraiture because I think my Potosi resident great grandfather’s portrait may have been painted by him too.

I very much enjoyed reading this article, which added to my knowledge of Hinchey’s life. I thought you would enjoy knowing that the self-portrait of William Hinchey has been in the collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art in Birmingham, Alabama since 2010. See: https://www.artsbma.org/collection/self-portrait-10/

Fascinating article ,many thanks. I’m interested to know if there is any known connection to the younger Irish-American artist working in St Louis, Cincinnati etc in the early 1870s?

My 3rd ggg grandmother, Nancy Rachel or Rachel Nancy Biddlecomb Camden is on the 1860 census of Iron county as living with his father and mother in law, Allen W Holloman in Arcadia. She was 80 years old. They both came from North Carolina and had lived at Avon, Saline township, Ste Genevieve County, Missouri. Her husband filed for divorce twice but never went to court. He, in his 60’s married a 14 year old girl who had lived with them in Ste Genevieve. Nothing else is heard of her. I’m wondering if she was working at the Arcadia Academy. I’d love to know where the diaries are so I can see if William ever mentioned or painted her.

Benjamin B. had a child with Francis “Fanny” Tubbs when she was 19. He was 66. They had 5 children together. She is buried in Newton Cemetery in Ellington Missouri. Two Tubbs girls were living with the Camdens. Fannys sister Sarah married Benjamin B.s youngest son, Benjamin H. in Ste Genevieve.Their youngest daughter is my grandma.

I found a portrait of William Hinchey (circa 1848 or 9)at the Mormon Church Deseret Industries store in North Seattle in (about) 2015, and it had his name and the store that he purchased his paintings supplies from on the reverse. It had no frame and a large L tear in it making it fairly cheap. I had it restored and corresponded with the Missouri Historical Society when they were just beginning to understand the importance of Hinchey, when the portrait in Alabama surfaced. I believed at the time the portrait I had was and earlier work than that one….. photo available!

Ray Swenson , now in St Petersburg Florida