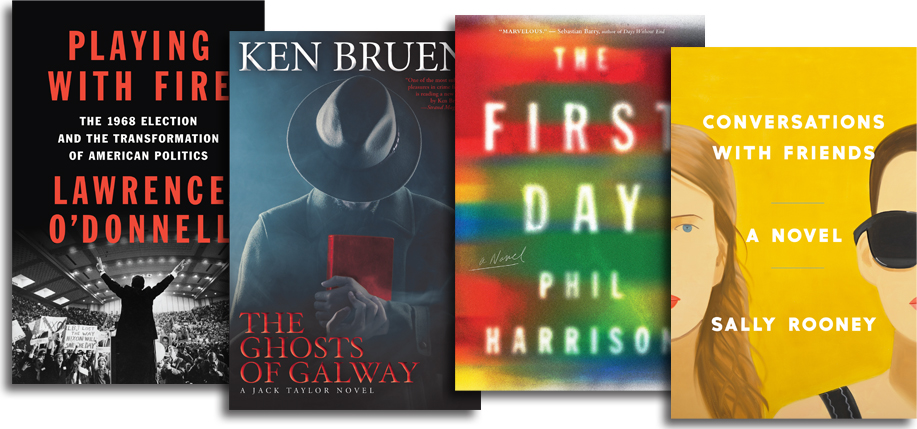

Recently published books of Irish and Irish American interest.

℘℘℘

NONFICTION

Playing with Fire: The 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics

By Lawrence O’Donnell

MSNBC pundit Lawrence O’Donnell found himself in an Irish feud a few months back with Donald Trump’s chief of staff John Kelly. O’Donnell, himself a Boston-born Irish American, blasted Kelly’s comments about an African American congresswoman.

“I know the neighborhood John Kelly comes from. I know the culture,” said O’Donnell. “You know what wasn’t sacred when he was a kid growing up? Black women.”

Whoever you agree with, this war of words epitomizes how nasty political debate has become. How did things get that way? In attempting to answer this very question, O’Donnell gets in touch with his more calm and cerebral side in a fascinating and timely new book, Playing With Fire: The 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics.

The big political story during this eventful and chaotic year was not whether or not Lyndon Johnson could win reelection against Republican candidate Richard Nixon, but who would challenge Johnson’s ability to even face Nixon. O’Donnell excellently chronicles the dramatic face-off between Irish Americans Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy – that is, until June, when Kennedy was assassinated.

Overall, O’Donnell manages to make lots of sense of this anarchic year, which also included the military unraveling in Vietnam and the explosive Democratic Convention in Chicago.

O’Donnell does miss some subtleties about the year, particularly in relation to Catholic voters, like Irish Americans, who began seriously flirting with more conservative politicians after years of loyalty to the Democratic party. (There is, however, a lot in the book about how Irish Catholicism influenced prominent figures like the Kennedys.) Still, O’Donnell did dig up this revealing nugget from a supporter of pro-segregationist presidential candidate George Wallace:

“I am a racist. I don’t even believe in Irish marrying Germans.”

This type of brazen comment, made 50 years ago, goes a long way towards explaining the tone of political debate today.

– Tom Deignan

(Penguin / 496 pp. / $28)

FICTION

The Ghosts of Galway

By Ken Bruen

If you’ve seen the engaging music video that accompanies Ed Sheeran’s slightly twee “Galway Girl” hit single, you’ll have a picture of a city filled with craic and ceol and whatever you’re having yourself. Actress Saoirse Ronan, comedian Tommy Tiernan and Love/Hate hoodlum Laurence Kinlan all play their parts to perfection, and all Bord Fáilte need to do is make sure it’s played all over the world and the tourists will surely come in their droves.

Ken Bruen’s The Ghosts of Galway is an altogether different kettle of fish, and his Galway girl would kill you as easily and effortlessly as she’d look at you. His hard-bitten detective Jack Taylor has not softened with age, and the book is rife with potshots he takes at anything that annoys him: Trump, ungrateful buskers, the Catholic church, the Irish water fiasco, Brexit, Fenians, and so on. He is still drinking too much and smoking, having won a slight health reprieve after a death’s-door diagnosis turned out to be slightly exaggerated. His attempt at suicide has failed and he’s made the reluctant decision to give life another chance.

When asked by a Ukrainian gangster to track down a supposedly priceless book of religious heresy, Jack finds the hefty paycheck hard to resist, although his search will bring him in close contact with the priests he professes to despise. The colorful Em, who has been flitting in and out of his life seamlessly, but not without trouble, is hanging around again. And where Em hangs out, the bodies quickly begin to pile up.

The ghosts of the title refer to the ghosts of Taylor’s past – the people who journey with him, despite his best efforts to leave them behind. Bruen’s trademark machine gun prose often sends word flying around the page, but it’s in keeping with the almost poetic meditations that occupy Taylor when he’s not actively fighting for his life. Ed Sheeran Galway-lite it ain’t!

– Darina Molloy

(The Mysterious Press / 330 pp. $25)

The First Day

By Phil Harrison

In his debut novel, The First Day, Phil Harrison tells a story of passion and betrayal, fury and heartbreak in a tone so steadfastly nonpartisan that it might just leave readers wondering how he didn’t boil over in the process. While emotions fly hard and fast between the principal characters of the text – Anna, a young scholar specializing in the work of Samuel Beckett, and Samuel Orr, a Protestant minister and family man with whom she enters into a zealous affair – Harrison, as narrator, tells their story with a near-scientific attention to the correlation and causation of what brings people together and tears them apart. The result is beyond effective – it’s addictive. The First Day is more than a novel, it’s a philosophical study hiding in plain sight.

Harrison, who wrote and directed his first feature-length film, The Good Man, in 2012, retains many cinematic techniques in his transition from screen to sheet. Most significantly, to his creations he is a distant god. Over the course of the narrative, he alters, fast-forwards, and often roadblocks their journeys to reveal not the essence of who they are, but what they stand for. The interrogation is merciless. Asked in an interview with the British literary magazine Litro whether the story had been with him for some time before he’d committed it to paper, he confirmed that it had always been more about the ideas: “How far can a person go while equally committed to his faith and his desire? To what extent does faith or desire compromise autonomy?”

The results of Anna and Samuel’s tryst are both tragic and full of promise. Years later, as the setting fades from Belfast to New York, their son must face this history. From further off, so too does Harrison. What he observes, unclouded by judgment and reported in stark, concise prose, is worth hearing about.

– Olivia O’Mahony

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt / 214 pp. / $23)

Conversations with Friends

By Sally Rooney

In Irish novels of the 20th century, the Church, the State, or social pressure (often conditioned by those first two aspects of Irish life) were the structural antagonist whose influence over the individual agency of a character had to be reckoned with – think Catholicism in Joyce, the government in Liam O’Flaherty, cultural mores in Edna O’Brien. Thank goodness the country is evolving and Irish literature along with it. Not that these are issues of the past, but with the recent post-crash socially liberal resurgence, church and state are no longer necessarily the main enemies of individual lives (the Eighth Amendment – Ireland’s pro-life constitutional provision – excepted).

In Sally Rooney’s debut novel, a sharp, sardonic, and hyperarticulate story of female friendship, anxiety, adultery, and burgeoning adulthood, it is not these old signifiers of control that exert their force over the book’s characters, but resolutely 21st century power structures – masculinity and feminism, capitalism and technology.

Conversations with Friends centers on two 20-year-old Trinity College students, Frances and Bobby, best friends since high school who also briefly dated. The novel opens at a poetry reading, where the two women perform a joint spoken word act and are recruited into the circle of Melissa, a well-known writer ten years their senior who wants to profile them as up-and-coming Irish literati. She takes them home for a nightcap to her large house in the Dublin suburbs, and introduces them to her husband, Nick, a semi-famous actor without much good work lately. Bobby and Melissa immediately get along. Nick and Frances soon enter into an affair (about which the novel, refreshingly, remains amoral).

Told from Frances’s perspective, the conversations of the book’s title take place in person, over email and chats, in texts, and on the phone. Both women are smart, at times arrestingly and callously so, constantly challenging each other and their friends with their intellect and irony. But both still have much to learn about the heady and heartbreaking transition between adolescence and adulthood, where high-minded ideals come crashing into the practicality of compromised ethics and moral dubiousness that attends growing up. (Example: When Frances and Nick finally have sex, she tells him, “We can sleep together if you want, but you should know I’m only doing it ironically.”)

Conversations with Friends doesn’t preach, it doesn’t contain “literary” descriptions of scenery or cityscapes, it barely even names the city of Dublin. Instead, it’s an insightful and damning study of how human beings talk to, through, and at each other, and the consequences of ignoring the staying power of words.

– Adam Farley

(Hogarth / 320 pp. / $26)

Leave a Reply