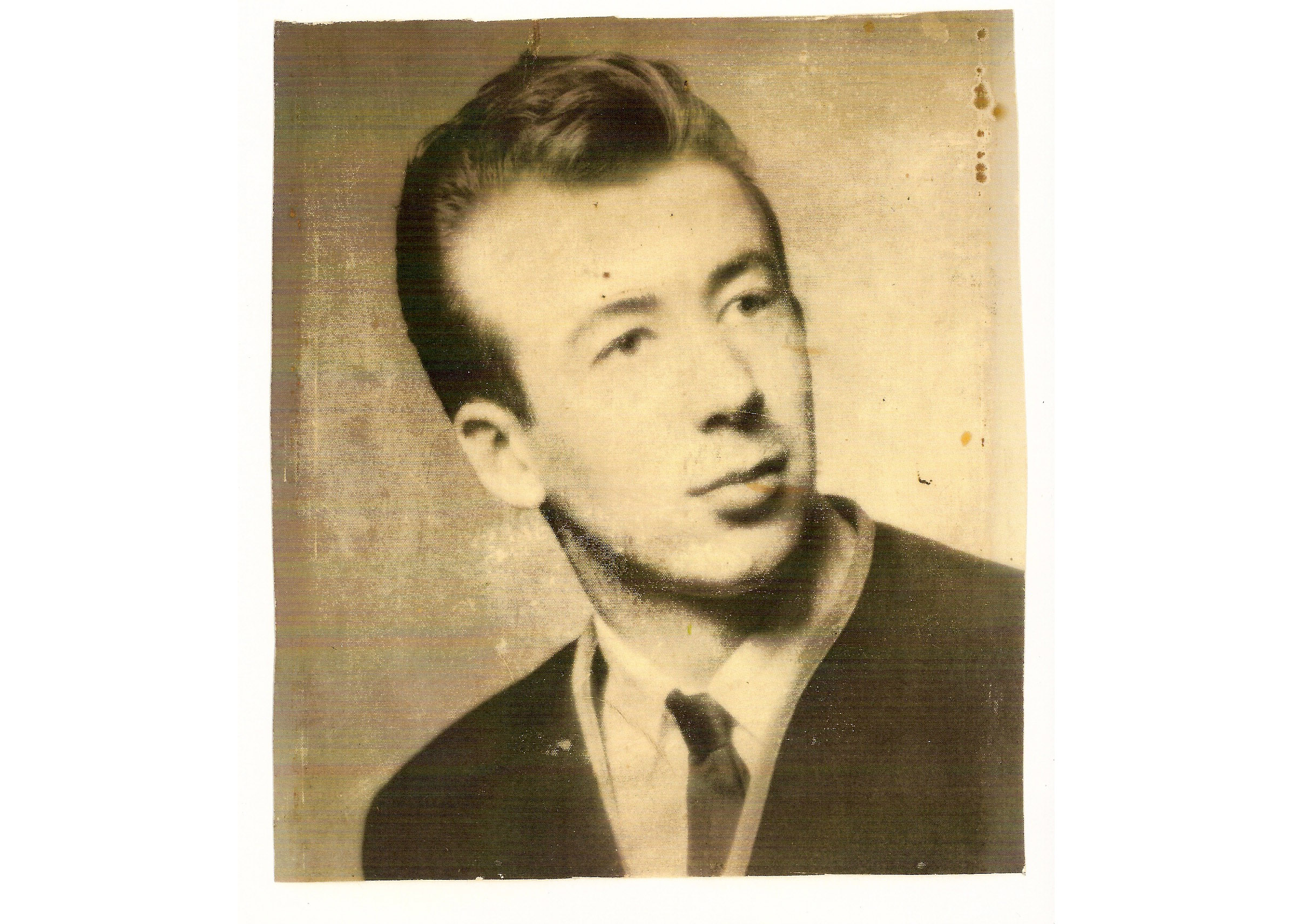

Michael Coyne is one of many Irish-born soldiers who served in Vietnam. A crewman on a Patton tank, he spent most of his time far from base on patrol in the jungle and rice paddies.

My name is Michael Coyne. I was born in Cornamona, Galway, 1945. When I was seven we moved here to Jenkinstown, County Meath, as part of the Land Commission Resettlement program. Our family, including myself, spoke Irish. When I was 16 my mother was dying and my uncle arranged for me to go to Chicago. I got a job with an Italian gardener. For six months, I went around the suburbs cutting shrubs and that kind of thing. My uncle then got me a job with a furrier by the name of Jerome McCarthy. I had a great time learning about furs and helping run the fashion shows in all the big hotels in Chicago.

In 1963, I turned 18 and had to sign up for the draft. I got called up two years later. Jerome McCarthy managed to get me off based on my job being vital. I’ve no idea why a furrier was classed as vital. I was called up two or three times and each time I was told to go home. However, on October 23, 1966, I was called up again. I went through the medical and all the paperwork as before, and they told me to go home. I was on edge and apprehensive and I said, “No, I want to go.” I was fed up with being called up. That was it. Off I went to Fort Campbell in Kentucky.

Fort Campbell was our introduction to the military. Here you got your hair cut, were issued your uniform, and learned the ideology of the U.S. Army. Then it was down to Fort Stuart in Georgia for basic training. We arrived on a bus, the Drill Sergeants were there to meet us. “Out! Out! Out!” they shouted. You had to be quick. Then at 05:00 the next morning it was, “Up! Up! Up!”

The training didn’t bother me. I was skinny and fit. I spent my time helping the poor devils who were breaking down crying. After basic, we were sent to Advanced Individual Training. One day an instructor came in and said, “We need two volunteers.” Two of us put up our hands. “You! You’re going to Air Traffic Control. You! Coyne, are going to Film Projection School.” I had no idea what that was but it sounded like a nice cushy number. After a three-week course learning about recording and editing film, I did a test and passed it. Some guys in the unit who had been in Vietnam with the Film Projection Unit said it was a piece of cake. So I thought, “I’ll volunteer for that.”

I went to the Administration Sergeant. He said no problem. The next day he called me back. “You are not a U.S. citizen. God damn! I am going to have to send all kinds of paperwork up to Washington to get security clearance for you.” That was all sorted and in April 1967, I flew from Tacoma, Washington, to Cam Ranh Bay, on the south-eastern coast of Vietnam, between Phan Rang and Nha Trang.

I was tired after the journey and the heat was killing me. We were give hammocks to sleep on and told we’d be called at 07:00 to parade and get further orders. I was flat out and missed the first call. At 11:00 there was another parade. I fell in and my name was called out. “Where were you at 07:00?” I was asked. “I heard nothing,” I said. “It’s going to cost you. You’re going up to Blackhorse.” I didn’t know what that meant. I’d never heard of Blackhorse, the 11th Armored Cavalry regiment famous for their exploits in World War II.

When I arrived in Xuan Loc, Blackhorse were just coming off Operation Manhattan, a thrust into the Long Nguyen Secret Zone by the 1st and 2nd Squadrons. This zone was a long-suspected regional headquarter of the Viet Cong.

Sixty tunnel complexes were uncovered, 1,884 fortifications were destroyed, and 621 tons of rice was evacuated during these operations.

Colonel Roy Farley was the newly-appointed commanding officer of the regiment. Two or three of us were paraded in front of him. “I see you’re an Irishman” Farley said. “What’s that you have,” he asked, pointing at my camera. “I’m a projectionist,” I said. “I show training films.” He bellowed out, “Ain’t got no room for no training films here. You can be my driver,” he said. “That’s good,” I thought. Well, I was at that for about a week. One evening I was smoking pot with a bunch of other lads. The next day the Colonel called me over. “Coyne, I hear you were smoking pot.” There was no point denying it. “Right, as punishment you are going up with the scouts.”

An ongoing operation at the time was Operation Kittyhawk. It began in April 1967 and ran to March 21, 1968. The Regiment was tasked to secure and pacify Long Khanh Province. It achieved three main objectives: Viet Cong were kept from interfering with travel by locals on the main roads, South Vietnamese were provided medical treatment in programs like MEDCAP and DENCAP, and finally, Reconnaissance In Force (RIF) operations were employed to keep the Viet Cong off balance, making it impossible for them to mount offensive operations. These operations brought us up to and into Cambodia and around the famous Iron Triangle.

The Iron Triangle, or Tam Giác Sắt in Vietnamese, was a 120-square mile area in the Bình Dương Province. It was an active stronghold of the Việt Minh – the coalition formed by Ho Chi Minh in 1941, originally to gain independence from France (the colonial power in Vietnam from the mid-19th century through 1954), that later opposed the U.S. and South Vietnam – located between the Saigon River on the west and the Tinh River on the east and bordering Route 13 about 25 miles north of Saigon. The southern apex was seven miles from Phu Cong, the capital of Bình Dương Province. Its proximity to Saigon concerted American and South Vietnamese efforts to destabilize the region as a power base for Viet Cong operations.

The Iron Triangle had a vast network of tunnels from which the Viet Cong operated. The tunnels, built during the war with the French colonialists during the 1945 – 1946 First Indochina War, were said to have a network of over 30,000 miles throughout North and South Vietnam. Hundreds of miles of this network were in the Iron Triangle. They were especially concentrated in the area around the town of Củ Chi.

As part of Kittyhawk, 1st and 3rd Squadrons carried out Operation Emporia from July 21-September 14. These were road clearing operations with limited RIF missions. As I was the spare man, I would get called down to check foxholes and tunnels regularly.

I was up with the scouts for three weeks. A replacement was needed on one of the tanks in 1st Platoon, Delta Company, 1st Squadron, after a trooper was killed. I was transferred there, and that’s where I remained.

A M48A3 Patton tank (named after General George S. Patton of World War II fame) had a crew of four: commander, gunner, loader, driver and back-deck gunner. My call sign was Delta13Charlie. Delta meant D Company, 13 was our tank, and Charlie was me. As in C for Coyne.

On our Patton tank I was the back-deck gunner – otherwise known as the spare man. I had an M60 machine gun, M79 grenade launcher, an M3 .45-cal. grease gun, and an M16 assault rifle. We didn’t use the range finder down in the turret that much. In the close environment of the jungle, visibility was very poor. My vantage point on top was critical. We lost four tanks in my time. I was also wounded four times. Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPGs) were a common enemy. They’d hit the tank and bits of shrapnel would go everywhere.

We rarely saw Base Camp as we were constantly on operations. Food, fuel, ammunition, and spare parts were all flown out to us by helicopter. The squadrons were self-sufficient. Tank engines were even changed in the middle of the jungle.

In the summer of 1967, the South Vietnamese presidential elections were being held. As part of Operation Valdosta I & II, the regiment was tasked with providing security at polling stations during the elections, and to maintain reaction forces to counter VC agitation. 1st and 3rd Squadrons operated in the Long Khánh District. The presidential election was held on September 3. The result was a victory for Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, a general in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and a cautious but calculating leader in the military junta that had ruled South Vietnam since 1965. He won 34.8 percent of the vote. The operation was a great success. Voter turnout was 83.2 percent.

On one occasion, up at Binh Long, we were conducting a RIF. Lieutenant Reid came by. “We need you to carry the radio and go up and check out a fork in the trail with myself and Smithy,” he instructed. Smithy was a sergeant from Kansas City. I put on the radio and went up to the fork about 1,000 meters up the trail. Lieutenant Reid and Sergeant Smith were in front to my left and right. The Lieutenant turned to me and said, “check that trail there.” Smithy said, “I’ll check it.” Up he jumped and went over. The next thing BANG! The top half of his body was gone. His legs were still standing there. Hard to believe, but his legs were still there. It was so fast. I looked down and parts of his rib cage was sticking in my arm.

Within a fraction of a second myself and Lieutenant Reid were on the ground, our tanks were firing over our heads. The rockets that had hit us had gone on to hit the tanks. The Patton tank used the 90mm M377 canister anti-personnel round. This canister projectile was filled with 1,281 spherical steel pellets for use at short ranges. It was particularly effective against personnel in dense foliage. The tanks opened up, and all around us the jungle started to come down.

We went from one operation to another.

Patrols and more patrols. On December 5, Colonel Roy Farley was replaced by Colonel Jack MacFarlane. From December 14 to 21, we conducted Operation Quicksilver. 1st and 2nd Squadrons were tasked with the security of the highway between Bến Cát and Phuroc Ninh. Its purpose was to secure routes that moved logistical personnel of the 101st Airborne Division between Bình Long and Tây Ninh Provinces. Cordon, search, and RIF missions were carried out.

Quicksilver rolled into Operation Fargo, December 21-January 2, 1968. Fargo was a regimental seized operation. RIFs were conducted in Bình Long and Tây Ninh Provinces and Route 13 was opened to military traffic for the very first time.

When we found a tunnel, as spare man I was always sent down to check it out. You grabbed your .45 and bayonet and down you went. On one occasion, I jumped down and found a room with a Singer sewing machine. In the corner of the room there was a trap door. I knew the Viet Cong (VC) or North Vietnamese (NVA) soldiers were on the other side. And they knew I knew they were there. I sat down and started peddling away on the sewing machine. I sat there for around 15 or 20 minutes peddling away. “Nothing down there except a sewing machine if you want it,” I said, when I crawled back up to the tank. If I’d opened that trap door, I wouldn’t be here now.

In the villages, I was always the one to drop down and talk to the villagers. I’d ask them “Where VC? Where VC?” They’d always reply “No VC! No VC!” The Sergeant asked me one day, “God Damn Coyne! How do you speak to them?” “I speak English,” I told him. The Vietnamese spoke some English. Some better than others.

One time, this old lady shouted, “Number 1! Number 1!” The guys on the tank just thought the villagers liked me. I knew what she meant. I was marked as a target. I got back up on the tank and told the commander, “They’re friendlies, let’s go!” You avoided a fire fight when you could.

On another day, we were the lead tank. We came to a stream. I said to Danny Kind, “that looks like a mine.” Danny agreed. We stopped the tank and called in the engineer minesweepers. I could hear on the radio in my helmet, a captain shouting “Come on move it! I have a schedule to keep to.” He sent down an intelligence officer, who was also a captain. He started kicking the ground with his foot. I was looking down from the top of the tank at him. Danny shouted, “Sir, don’t go over there. It’s not safe.” The officer replied back, “I didn’t do all that training in the States for nothing.” BANG! He went 100 feet in the air. All that we found of him was his boot. His son wrote to me for some time after. I initially told him his father had stepped on the mine. Eventually I had to tell him he kicked it. He asked me why his father had kicked it. I told him he was under severe pressure to get the column moving again.

I remember a chaplain arriving in camp. “Coyne, you’re a Catholic, aren’t you?” I replied yes. “Report to the chaplain.” We took a walk into the jungle. There were two big pits. Around 14 American dead soldiers. The chaplain said a few words, but wanted me then to also say some prayers. All I could remember was the Hail Mary.

“What’s that priest doing over there at that other pit?” I asked. The chaplain replied, “That’s for the Protestants.” Can you believe that? Even in the middle of Vietnam they separated the Catholics from the Protestants.

On January 30, 1968, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, coinciding with the Tết holiday (Vietnamese New Year). One of the largest campaigns of the war, it was fought over three phases from January 30 through September 23, 1968. The offensive centered around surprise attacks against military and civilian command and control centers throughout South Vietnam.

On the night of January 30, we were across the border in Cambodia and had just gone through a continuous fire fight to get there. When the offensive began we had to turn around and fight our way back to protect Saigon. We left tanks and Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs) burning all along the road but we had to keep moving. RPGs kept coming at us, but we had to keep going and get through it. Saigon was a battlefield. Scenes just like what you would see in Syria on TV today. The place was being torn apart.

Operation Adairsville began on January 31. Word was received by II Field Force HQs to immediately re-deploy to the Long Binh/Biên Hòa area to relieve threatened installations. At 14:00, 1st Squadron was called to move from our position south of the Michelin Rubber Plantation to the II Field Force Headquarters. The 2nd Squadron moved from north of the plantation to the III Corps POW Compound were enemy soldiers were sure to attempt to liberate the camp. The 3rd Squadron moved from An Lộc to III Corps Army, Republic of South Vietnam (ARVN) Headquarters. It took only 14 hours and 80 miles to arrive in position after first being alerted.

1st and 2nd Squadrons continued security operations in the Long Binh/Biên Hòa area and the area around Blackhorse Base Camp under Operation Alcorn Cove which began on March 22. This was a joint mission with the ARVN 18th Division and 25th Division. This operation rolled into Operation Toan Thang – a joint operation involving the 1st and 25th Infantry Divisions. Toan Thang was the first of a series of massive operations combining the assets and operations of the ARVN’s III Corps and our II Field Force. The purpose of this operation was to maintain the post-Tet pressure on the enemy and to drive all remaining NVA/VC troops from III Corps and the Saigon area. A total of 42 U.S. combat battalions participated at one time or another in Toan Thang.

The Tet Offensive allowed the regiment a chance to fight the enemy formations in open combat. Colonel MacFarlane was wounded in March 1968, and replaced on March 12, by Colonel Leonard Holder. He was killed only a few weeks later on March 21. Colonel Charles Gorder took command of the regiment on March 22.

The VC and NVA launched Phase II of Tet in early May. This was known as the May Offensive, Little Tet, or Mini-Tet. The enemy struck 119 targets throughout South Vietnam, including Saigon. 13 VC battalions, slipped through the cordon and again turned Saigon into a battlefield. Mini Tet was nearly worse than the main offensive.

In early May, I came across a guy from Kentucky. He was bent over, wrecked with worry. He had a wife and four kids. On May 13, the tanks and APCs were all lined up for a counterattack near Saigon. I can still remember our Captain with a machete in one hand. As he dropped his hand with the machete, he shouted, “Charge!” We all rolled forward, firing as we moved.

Rockets and tracer rounds came at us from all over. Bullets were flying everywhere. I was on the top deck with the M60. On the tank beside me my counterpart, a guy from Dakota, Washington, was dancing away. Bullets flying all around. I thought, “He’s fucking gone.”

At the end of the battle we counted 14 to 15 holes in his clothes. Not a scratch on him. That’s the way it played out. He was off his head on drugs. As for the poor devil from Kentucky, his track got hit. They were nearly all killed. The whole unit had to pull back. All night long we could hear them calling: “Help, help.” Awful shit.

On May 30, the tanks and the APCs were all in the rice paddies at Đức Hòa, a rural district in the Mekong Delta region. There was an intense fire fight. Nearly everybody ran out of ammunition. The Captain was standing with a prisoner. He said to us, “There’s four APCs out there and there’s nine of our wounded in them. We need two or three guys to go out there and get them.” He looked at me. I got my M16 and headed out with Staff Sargeant Francis Hinnigan.

It was like wading through mud. Next thing Hinnigan went down. Machine gun fire zeroed in on where we were. He was hit in the shoulder and leg. I kept going; bullets were whizzing all around. I got hit. But I got there. There were nine guys wounded, some of them were in bits – legs and other parts missing. Another guy was wounded, but he was able to give me a hand. We got them all into a track (M113 APC). I got into the front and drove them out of there, all the time under fire.

I caught malaria in mid-June that year. They flew me out of the jungle. I was so sick. By the time I got to hospital and they did tests, the malaria had gone into relapse so nothing showed up. Back on a chopper I was put and sent back to my unit. Within 12 hours I’d passed out. I was sent from hospital to hospital; Long Bihn hospital, Alaska, and then Valley Forge. I wouldn’t wish malaria on anyone. My temperature was so high my brain should have been cooked! I never returned to Vietnam after that. Colonel Gorder was replaced on July 15, by none other than Colonel George S. Patton Jr., he son of General George S. Patton IV of World War II fame. Colonel Patton requested that the regiment test the M551 Sheridan. 1st Squadron were the first to use the new tank. While all this was happening, I was in hospital. My military service was effectively over and I was “separated out” on disability on August 29, 1968.

I went back to work for the fur company in Chicago. My boss’s son had gotten killed in a car accident while I was away. He couldn’t understand how I’d survived Vietnam and his son gets killed in a car crash. He was miserable. I worked for a bit with my brother in Indiana, got in trouble with the law. I eventually made my way to London where I worked as an electrician. In 1972, I spent a year in Saudi

Arabia working on power plants. We were pulled out when the 1973 Arab-Israeli War broke out. Christmas 1973, I was broke. Wandering the streets, I looked up and saw a sign for Bank Line Shipping. Days later I was on a flight to Panama to meet my ship. That was another adventure.

I was not the same guy after Vietnam. One thing stays with you after you have been in a battle – you never want to be in another one. For a least five or six years after the war I was a headbanger. I can’t remember mostly what I was doing. I didn’t give a shit about anything and I couldn’t remember anything. My head was a right mess. It still lingers.

Epilogue

Michael returned to Ireland in 1979. He became a founding member of the JFK Post, American Legion (Dublin), in 1996, he is also a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Irish Veterans, American Veterans of Vietnam and the Blackhorse 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment Association. Michael later took a case against the U.S. government over the effects of Agent Orange. (Agent Orange was a chemical used to defoliate the jungles in Vietnam). He lives today in Jenkinstown, County Meath, with his wife Libby, two sons, Thomas and Michael, and their daughter, Vanessa. ♦

_______________

Wesley Bourke is editor of Ireland’s Military Story magazine, where this article first appeared.

Dear Michael Coyne. Are you a professional writer? If not, I strongly advise you to become one. I’m 72 myself and pub’d 4 history articles this summer and very much enjoy writing and publishing.

You need to get away from the pot and filthy language. Your description of the American response to a Vietnamese ambush is worthy of Joseph Conrad..

Once again, if you’re not yet a professional writer, you should become one. You were spared by the terrible war – maybe to write – you have the Irish magic.

Good luck with it!

Peadar

Brilliant story !

This is truly a great story. In 1966 I shared an apt. in the Fordham section of the Bronx with Kerry native DANNY CARMODY who had recently been discharged from the U.S. Army but never spoke of his military services. In the summer of ’66, he and 2 or 3 friends planned to spend a Sat. fishing in the NYC reservoirs in the Catskills so Carmody got a State fishing license and a fishing pole. That Sat. I arrived home from my night job at 7AM and found the Army veteran’s fishing rod inside the door. Thinking he had overslept, I rushed into his room and hurriedly awakened him. No, he had not missed his fishing trip; his application for a NYC permit to fish in the reservoirs had been DENIED for lack of citizenship. Then Carmody told me this story: When he got a notice to report to Fort Dix for basic training, no one asked him about citizenship. A few months after basic training, he was sent to Vietnam with his unit, but the question of citizenship never arose. During his 2cmonths in Vietnam, he often was sent on night patrols in the jungle that was infested with V.C. – but NEVER any mention of his lack of citizenship.

Ba maith a rá le Micheál go bhfuilim lánsásta le do chuid saighdúireachta agus do chuid scribneoireachta. Legionnaire # 200229955

Ah, well. That’s too bad. Known as the Swamp, that President Trump is draining, God bless him.

I’m a handicapped vet. Billions of dollars have been invested in establishing medical services for us vets but most are told they are not eligible for dental benefits. Why? – so they can be sold “low cost” dental insurance by big companies. Is that a croak from the Swamp or what?

Hopefully our new President will fix it.

Best wishes,

Pat Howard

US’nAye

Hi, again, Michael. This time I see you did not actually write this article but dictated it to Wesley Bourke. What a lot of detail! Did you keep a journal? Impressive.

Yes, we were in a war where there was no real leadership on our side, nor were we ready for it. How times have changed!

Sounds like you deserve the Medal of Honor for May 30. Might have got it if we’d won the war, like Audie Murphy. Ireland has just been a factory for soldiers!

Your life certainly sounds like Voltaire’s Candide!

Congratulations on all you survive, even the typos. Too bad about them. I’ve warned Patti’s staff to stay away from the bar till they’ve put the articles to bed.

Best wishes, I hope you’re feeling well. I’m in a wheelchair myself, arthritis, but enjoy friends and writing and a beautiful view of a tidal lake in Oakland, California.

Pat

Hi Michael,

Well, just read your whole story here. My parents were born in Ireland – Mayo & Castlebar and I have been to both of their homes, when they were children, then immigrated to America Chicago. My wife’s parents are also from Ireland, My Mother in law – Mayo – village of Attymass, my Father in law was from Leitrim – that was the only place my daughter and I weren’t when I went back a few years back. My Cousins still live in both houses. So that is my Irish Roots. But I fought in Vietnam the same area as you. Was in the 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry – 25th Infantry Division, Cu Chi, so some of those places like the Iron Triangle, HO BO, Bo LO, woods and others. I was a Cavalry Scout and was there before you were. Have buddies that also served in your Unit the 11 ARC. We meet with 100 Vietnam Veterans for coffee ever Tuesday morning here in Chicago where I live. And same neighborhood all my life. my Adult children went to the same Catholic Grammar school I did. First of All WELCOME HOME Brother. Wrote a couple of books one about my time – Before, During, And After Vietnam – the myself and another Vietnam Veteran 101st Infantry Division just finished it. The Day we Finally Came Back From Vietnam – Roger McGill & Harry Beyne III. Who is also Irish American. It is on Amazon – Thanks again for your service.