She was the original Patient Zero, a healthy and asymptomatic carrier of a deadly plague. Baptized in Ireland in 1869 as Mary Mallon, she was re-baptized in America as Typhoid Mary, a name conjuring evil and purposeful contagion, a name that carries a peculiar legacy – the notice in restrooms demanding, “Employees must wash their hands before returning to work.”

Orphaned as a child, Mary lived with her grandmother in County Tyrone, one of the poorest counties in the poorest country in Europe. In Ireland they may have been starving but Granny taught Mary how to scrounge for food and cook with what they had, making potato cakes and nettles over a peat fire. Granny and Mary were part of the new breed of post-Famine women, all tough, strong and independent. They were fighters – they had to be – and many years later, many miles away, the word “fighter” was often used to demonize Mary Mallon.

In 1883, Mary arrived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, an area teeming with immigrants, many sick and starving. She was 14 and worked, first, as the stereotypical Irish washerwoman. But the robust redhead was ambitious and saw cooking as her calling and a way out of poverty. Mary concocted a resume of employers and addresses that didn’t exist and managed to find work in the finest homes, starting in the scullery. In time she was head cook, using her now evolved talent to compete with recently imported French cuisiniers. Turn-of-the century New York was enjoying a foodie phase and Mary, with enormous ovens (not peat fires) and an excess of fresh foods and delicacies (not potatoes and nettles) at her disposal, emerged a true chef.

Her employers appreciated her managerial skills, shopping savvy, and varied menus and would host feasts prepared by their gifted, albeit Irish, cook. But Mary, unwilling and unwitting, was doing some hosting of her own – in her intestinal tract – where billions of Salmonella typhi bacteria were proliferating and thriving. Over the course of 15 years, she infected hundreds with typhoid fever and killed, estimates vary, somewhere between three and fifty victims.

Until Mary invaded wealthy households, it was held that typhoid fever, which killed 10 percent of its victims was, like cholera, influenza, and diphtheria, a disease of the slums spread by its unclean immigrants. The Lower East Side had created what health officials named the “miasma,” the collective term for the noxious gases of sewer, garbage, horse carcasses and manure – all the stuff of immigrant stink. But the miasma theory was as phony as Mary’s resume; it was bacteria that caused disease. And the disease of typhoid fever was transmitted by food and water that had been contaminated with human feces or urine.

Call it denial or delusion, Mary always claimed she never connected herself to the typhoid outbreaks that followed her arrivals. Why would she? She was stronger than most men and, to use what would become her lifetime mantra: “never sick a day in my life.” Mary may not have washed her hands as well or as often as she should and, of course, these were the days before cooks wore gloves. Still, she must have seen it was more than coincidence that typhoid seemed to shadow her. But she proceeded with blithe indifference…until August, 1906.

A prosperous New York banker, Charles Henry Warren rented a house in Oyster Bay, Long Island, close to a home inhabited by then-president Theodore Roosevelt. In early August, Mary was sent in as a relief cook and within three weeks, the usual incubation time for typhoid fever, six of the eleven people in the Warren household had come down with the disease. What was a disease of the slums doing in the president’s backyard?

The usual suspects – drinking water, dairy supplies and the old woman who sold shellfish – were examined and quickly eliminated. Into the picture comes Dr. George Soper, a very ambitious sanitary engineer and something of a sleuth. Interviewing the Warren family, Soper learned there was a cook, since departed, whose employment coincided with the outbreak. Her name was Mary Mallon. The cook’s specialty, Soper learned, was peach cobbler and ice cream, a dish that, since it required no heating, was teeming with Mary’s typhoid bacilli.

Much like the CDC researchers in the 1980s who thumbed the paisley address book of airline steward Gaetan Dugas, the patient zero of the AIDS epidemic, Soper trolled the employment agencies that staffed private kitchens and retrieved the name of Mary’s employers from 1900 to 1907. He discovered that typhoid had struck seven of the last eight families where she worked. He learned, too, that in all the stricken households she had lovingly iced and nursed the victims – one employer even gave her a $50 tip.

Soper closed in on Mary when she was head chef at the Park Avenue home of Walter Bowen, where a daughter and maid had already come down with typhoid. Mary was in the kitchen wiping duck grease off her hands when she felt the presence of a stranger. Dr. Soper was standing over her and forgoing any formalities, asked for samples of her feces and urine. Who could blame her for coming after him with a roasting fork? Too late, he tried to explain that she was sick and, worse, she was a typhoid carrier. She hadn’t a clue what he was talking about and began shouting, along with expletives, “I’ve never been sick a day in my life!”

Soper kept insisting; Mary kept resisting, poking the roasting fork in the face of the spindly civil servant. He quickly rushed off.

Besides the multiplying typhoid bacteria in her body, Mary had another problem: she was Irish, a member of a despised underclass portrayed by cartoonist Thomas Nast as drunken brawling men and brawny women, only slightly elevated from apes. It didn’t help that Mary had “moral failings,” as evidenced by her relationship with a degenerate alcoholic, German immigrant, Alfred Breihof, who lived off her and with her in a dumpy set of rooms.

Learning of Breihof’s existence, the very sober Dr. Soper joined him at a bar, plied him with drinks and questions about Mary. Breihof, a snootful in situ, takes his new friend to their apartment where they wait for Mary. She arrives – pursuer and prey confront each other until Mary tosses him out with, as he later wrote, “a volley of imprecations from the head of the stairs.”

Soper now goes to the Department of Health demanding Mary be taken into custody and quarantined. He returns to the Bowen house with a woman doctor, Dr. Josephine Baker, but Mary spots her captors. Helped by her fellow domestics, she jumps over a fence and hides in a neighboring outhouse for three hours. Finally, five policemen drag her, kicking and cursing, into an ambulance where Dr. Baker proceeded to sit on her, an experience the doctor described as “being in a cage with an angry lion.”

Mary is taken to Willard Parker hospital, put in quarantine to lie among the dead and dying. A picture of her taken at that time shows a woman in her 40’s, obviously very healthy and very angry, glaring at the camera with a look that could have atomized lower Manhattan. Finally, Soper’s wish is granted and Mary’s stools were tested. The verdict: “a pure culture of typhoid.” It was further determined that her gallbladder was the bacteria’s breeding ground and her gallstones, a residence of sorts. The cook’s goose, as it were, was cooked.

From Willard Parker, she was committed to North Brother Island, “Plague Island,” on the East River between Riker’s Island and the Bronx. She refused to have her gallbladder removed, confirming to medical authorities that, besides being an ignorant, filthy Mick, she was a killer too. By the end of 1907, Mary was in solitary confinement in a small cottage, her one-woman leper colony. As a practicing Catholic, Mary may have preferred demons to be inhabiting her body since then she could call a priest. But no exorcist could do help with Salmonella typhi.

Mary refused to give up. Although authorities assumed she was illiterate, she was an accomplished letter writer and pled her case to authorities. She was completely healthy, yet confined – without a trial – to solitary confinement for two years, forced to be “a peep show.” George O’Neill took her case and arranged for a hearing before the New York Supreme Court. Arriving in the city, she was a tabloid sensation, a favorite of the Hearst papers who gave her a name that stayed with her forever, a name she hated, “Typhoid Mary.” Spectators crammed the sweaty courtroom and, in a hysteria similar to the early days of the AIDS crisis, were both thrilled and anxious, afraid to breathe near her or touch anything she had touched. She lost her case.

Within two years, sentiment had shifted and there was a new Commissioner of Health. It seems that in the rest of the country, asymptomatic carriers were no longer quarantined if they reported for regular testing and didn’t work in the food industry. In this new climate, Mary was released; she signed an affidavit promising to show up for screenings and to “change her occupation, that of cook.”

Now free, Mary felt like an Untouchable, a woman who could be recognized and shamed, a woman completely alone. This might explain her reconciling with the bad boyfriend, even nursing Breihof until he died of a heart ailment. At 41, she found herself, again, a washerwoman barely able to survive on the miserable wages. The cook who didn’t thoroughly wash her hands was now condemned to a life of having her hands submerged in scalding water for 12 hours a day. Never one to follow orders, Mary stopped reporting to the Department of Health and just… disappeared. When she finally surfaced she took on the odd cooking job and wasn’t caught. Emboldened and determined to find more lucrative work, she changed her name to Mrs. Mary Brown.

Mrs. Brown got a job in the Sloan Maternity Hospital, winning the affection of staff and coworkers who, in clueless but prescient banter, dubbed her “Typhoid Mary,” a joke she went along with. But, levity didn’t stop Mary from bringing her apparently inexhaustible supply of typhoid bacteria with her. The eventual epidemic struck the hospital, infecting 25 and killing 2, prompting the desperate hospital director to call Soper, who confirmed the cook as culprit. Now when the police came and surrounded her house, she gave in without a fight.

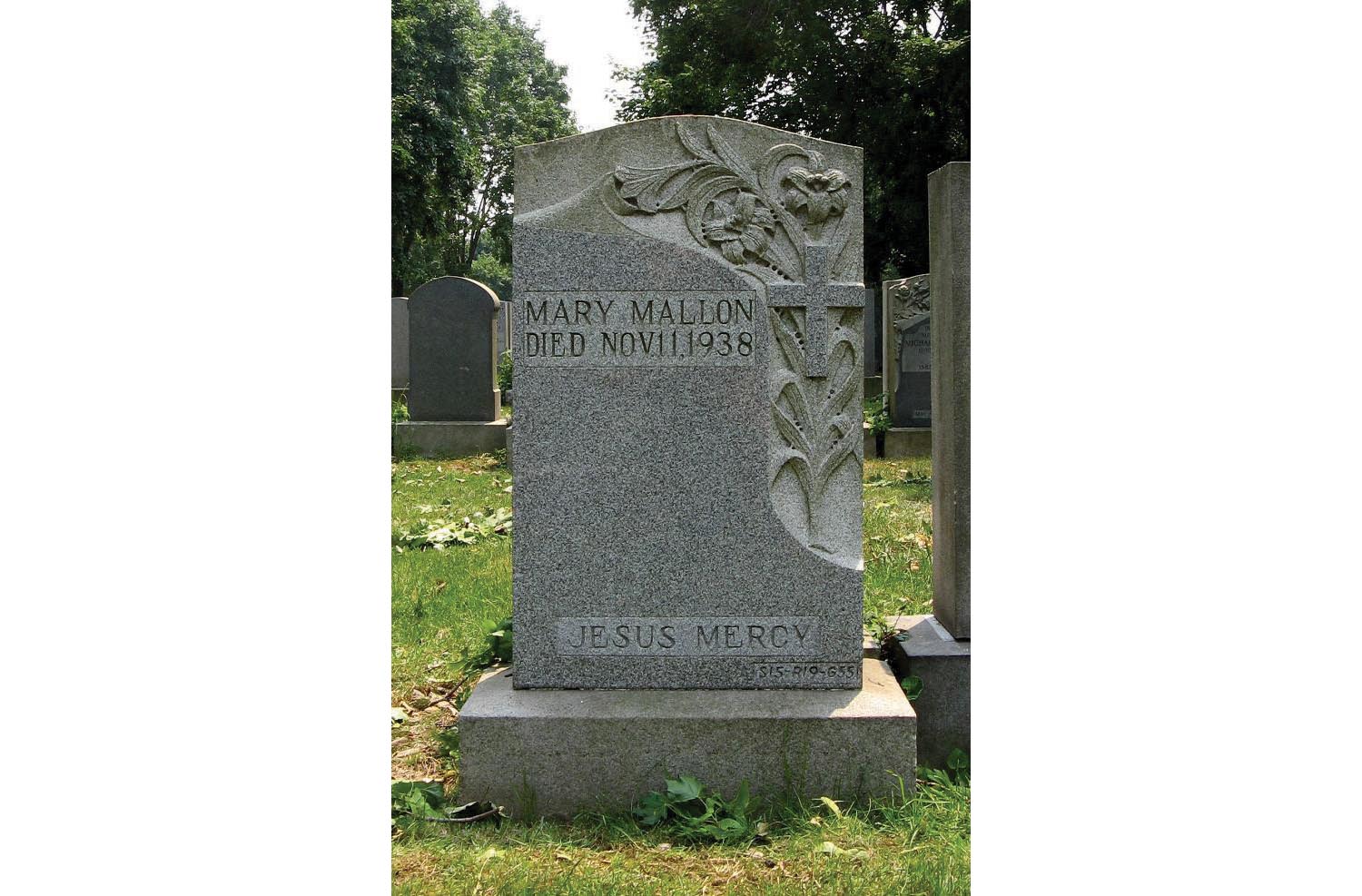

By 1915, Mary was back on North Brother Island where she would stay for the rest of her life. This time she was more social, working in the lab, embroidering and oddly, beginning to look like a man. She frequently visited nearby St. Luke’s, the church where her funeral was held in 1938. Only nine people attended the mass and none signed the guest book, isolating her even at the very end. She was 69 and her autopsy revealed she still had typhoid.

In 2013, Mary Mallon, still a medical legend, inspired a Stanford University team of microbiologists and immunologists to study her case and determine how her body was able to neutralize typhoid fever. Usually, when Salmonella typhi enter the body, macrophages – the Pac-Man-like attack cells of the immune system – gobble up the bacteria. If they fail, the victim succumbs to the disease. Mary, at some point in her life, was indeed infected with typhoid but her macrophages did not attack. Instead, they offered a hospitable environment to the bacteria, allowing them to hide in her gut, provide courier service to the lymph node and shed deadly pathogens while she never had as much as a mild cold. She was telling the truth when she said she was never sick a day in her life.

Typhoid fever has the distinction of being mankind’s oldest recognizable disease. Pesky and microscopic Salmonella typhi caused the Great Plague of Athens in 430 BC, a devastation that allowed Sparta to claim victory over Greece in the Peloponnesian War. In the 20th century, industrialized nations with antibiotics and improved sanitation claimed victory over typhoid and other infectious diseases. But in developing countries with poor sewage and without sufficient medical care, typhoid is still a threat. In Africa and Asia, new and virulent strains of typhoid have emerged, resistant to multiple antibiotics, now making, again, the disease difficult to treat.

Mary Mallon provided the template for what the medical world now terms a “super-spreader,” one who spreads disease in a disproportionate way. This phenomenon is now defined as the “80/20 Rule:” 80 percent of infections are caused by 20 percent of individuals who are infected but not necessarily sick. When American scientists analyzed the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone, they determined that super-spreaders attacked 61 percent of the victims. During the SARS pandemic, super-spreaders were responsible for 75 percent of infections in Hong Kong and Singapore – one 26-year-old man, over a short stay in a Hong Kong hospital, contaminated 156 victims including hospital staff, patients and visitors.

Current medical reports and press releases, attempting to explain contagion and super-spreaders frequently begin with an obligatory paragraph, the story of an Irish cook in early 20th century New York, a woman they call Typhoid Mary. ♦

_______________

This article was originally published in Irish America’s August / September 2017 issue.

I am researching Typhoid Mary, and there are a number of facts in this article that I have not encountered in other sources. Can you tell me what sources were used in the writing of the above article (“What You Didn’t Known About Typhoid Mary”)?

Thank you for your help.

A. Porter