Montreal’s memorial to Irish Famine victims.

℘℘℘

In 1997, Irish people around the world will remember the 150th anniversary of the Famine that resulted in one million deaths and forced one million and a half to emigrate to Canada and the United States. The deplorable conditions these immigrants endured aboard ship resulted in a typhus epidemic that decimated many en route to a new a life in North America.

The island of Grosse Ile in the St. Lawrence river, which was used s a quarantine station, remains the most significant memorial of this tragedy outside Ireland (thousands of Irish are buried there in mass graves) but here in Montreal in the area of the Black Stone, also known as the Ship Fever Monument, many more who died as the tragedy continued inland, are buried.

The influx of death ships arriving in Canada in 1847 taxed the facilities at Gross Ile. Physical appearance became the basis upon which the medical personnel place the immigrants in quarantine or let them proceed further. This resulted in the epidemic spreading further into the country. Many who continued by ship towards Montreal were contaminated by the disease and this became apparent when the first arrivals came ashore at the Port of Montreal.

The Montreal authorities took steps to have all further ships containing Irish immigrants directed to an area outside the town known as Windmill Point in the Goose Village area of Pointe St. Charles, where three large sheds were built to house the stricken, but soon the sick became so numerous that a further nineteen shed had to be built.

After a few weeks the sheds were infested with bugs. Straw mats were putrid and a scant supply of linen rapidly turned black. There were not enough doctors, not enough nuns or priests to administer to the dying.

The mounting numbers of people suffering and dying from the typhus put Montreal into a state of panic. John Loye, the brilliant innovative Irish Montrealer, related the story his grandmother Margaret Dowling told him she witnessed at Notre Dame and McGill Streets.

“A young Irish girl, stricken by the disease, had wandered into the the City, dressed in a nightgown and holding tin cup in her hand. A policeman had a to keep the citizens clear of her for fear of contamination until she could be returned to the quarantine of the sheds. A military cordon had to be established around the area of the sheds to contain the infected immigrants.”

Many charitable Montrealers came to assist the suffering and the dying. Fr. Joseph Connolly, the first pastor of St. Patrick’s Church, built by the Irish that same year, was but one of the many who risked has life to serve the dying because “if I prepared for death and consigned to the silent grave for a period of six weeks or more some 50 adult persons per day, I was but doing what every priest would be bound to do under similar circumstances.”

Numerous doctors, nurses, nuns and service personnel who tried to help, including the Mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills, and three priests from St. Patrick’s, Fathers Richards, Morgan and McInerny, all perished from the disease.

On the ceiling under the choir loft at the entrance to the Bonsecours Church in Old Montreal there is a painting of the nuns ministering to the suffering and dying Irish immigrants. Not many know of it.

Forgotten by many also is the story of Sister McMullen, the Superior of the Grey Nuns, who open witnessing the appalling misery and suffering in the sheds returned to the convent and addressed the nuns.

“Sisters, I have seen a sight today that I shall never forget. I went to Point St. Charles and found hundreds of sick and dying huddled together. The stench emanating from them is too great for even the strongest of constitution. The air is filled with the groans of the suffering. Death is there is its most appalling aspect. Those who thus cry aloud in their agony are strangers, and their hands are outstretched for relief. Sisters, the plague is contagious.”

At this point, it is said that she burst into tears and had to stop speaking. When the recovered her voice she simply added, “In sending you there, I am signing your death warrant, but you are free to accept or refuse.” There were a few moments of silence while their vows were being put to the test before the nuns all arose and stood before the Superior. Together they said as if in chorus, “I am ready.” Sister McMullen chose eight of the nuns and the following morning they went to Pointe St. Charles to the sheds. The following is from the memoirs of one of the Grey Nuns who administered tot he sick and dying, as published in the Montreal Gazette.

“I nearly fainted when I approached the entrance to this sepulcher. The smell suffocated me. I saw a number of beings with distorted features and discolored bodies lying heaped together on the ground looking like so many corpses.

“I knew not what to do, I could not advance without treading on one or another helpless create in my way. While in this perplexity I was recalled to action by seeing the frantic efforts of a poor man trying to extricate himself from among the prostrate crowds, his features at the same time expressing an intensity of horror. Stepping with precaution, placing first one foot, then the other where a space could be found, I managed to get near the patient …

“We set to work quickly. Clearing a small passage, we first carried out the dead bodies, and the, after strewing the floor with straw, we replaced thereon the living who soon had to be removed in their turn.”

Estimates of the dead range from 20,000 to 30,000, according to historian Tim Slattery who was interviewed by Linda Dieble for the Gazette in 1972. Although thousands were buried in a n open pit of quicklime in a cemetery near the Victoria Birdge, the bones of victims are strewn from Cape Clear to Cape Race and up the St. Lawrence to the Great Lakes.

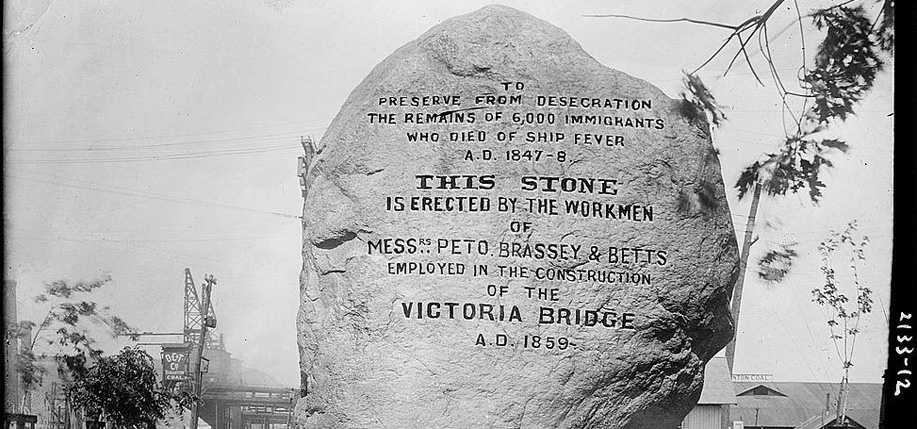

In 1859, the workmen building the Victoria Bridge uncovered the cemetery, and having taken a massive boulder, ten feet high, from the river decided to mark the final resting place of those whose dreams of a new life in a new land were not to be.

On it there is a plaque:

To preserve from desecration

The remains of 6,000 immigrants

Who died of ship-fever

a.d. 1847-48

This stone is erected by the workmen of Messrs. Peto, Brassey, and Betts Employed in the construction of the Victoria Bridge a.d. 1859.

The “Black Stone” was erected and dedicated on December 1, 1859.

The dedication was conducted by the Lord Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Montreal, and the area of the Stone remained peaceful until 1901 when the Grand Trunk Railway moved the Stone to advance their rail lines.

The Irish community rose up to denounce the move and legal action was taken against the Railway. The Railway was legally capable of expropriating the land as the defenders had not legal title. This changed dramatically when the Right Reverend John Farthing, Anglican Bishop of Montreal, discovered that the deed to the land had been left in perpetuity to the Anglican Bishop of Montreal by Thomas Brassey, of the construction company who had erected the Victoria Bridge. By the time the legal case ended it was 1911 and a large area was covered by rail tracks. A compromise was effected and the Stone was replaced in the cemetery area, which was by now one-third of the original size.

In July 1941, while working on a pedestrian tunnel, the workers of Kennedy Construction discovered five coffins containing the earthly remains of ship fever victims. A few weeks later another seven were unearthed. J.P. Feron Funeral Homes provided wooden coffins and the re-burial took place at the monument lot.

In 1966, the city of Montreal wanted to make drastic road changes for “Expo 67” and wanted to move the Stone to make way for the widening of Bridge Street. The Irish community again, with the assistance of the Irish historian Tim Slattery and then City Councillor Ken McKenna persuaded the city to move the road instead of the Black Stone. This created the island effected of the monument lot with traffic to and from Montreal going around the lot.

In the ensuing years the Irish in Montreal have fought many battles with the city to ensure that the Black Stone monument remains as a fitting memorial to those Irish immigrants who perished in the tragic year of 1847. The Ancient Order of Hibernians have for over 100 years kept the memory of these Irish alive and on the last Sunday of May each year they organize a “March to the Stone” which is preceded by a Memorial Mass promoted by the United Irish Societies of Montreal.

Official requests have been made to the City of Montreal and the government of Canada for historical status of this memorial, and plans are being made to erect a Celtic cross in the cemetery, in memory of those poor souls who sought a better life, but found only a quicklime grave an ocean away from home. May they rest in peace. ♦

_______________

This article originally appeared in the January / February 1996 issue of Irish America.

Update: Plans for the above-mentioned Celtic cross, forecasted for future construction by the Irish of Montreal, have yet to come to fruition. What continues to take precedence is the development of infrastructure in the area. It’s noteworthy that in 1901, the Black Stone was moved to accommodate the Grand Trunk Railway line expansion, and in 2017, the issue proves itself to be a recurring one. Hydro-Québec have purchased the land targeted for a memorial site by the Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation to accommodate an upcoming Réseau électrique métropolitain (REM) train substation. Mayor of Montreal Denis Coderre initially pledged his support for the memorial park, though now insists the substation construction must go ahead. Mayor Coderre has told the Montreal Gazette that the city will continue to search for a compromise.

Leave a Reply