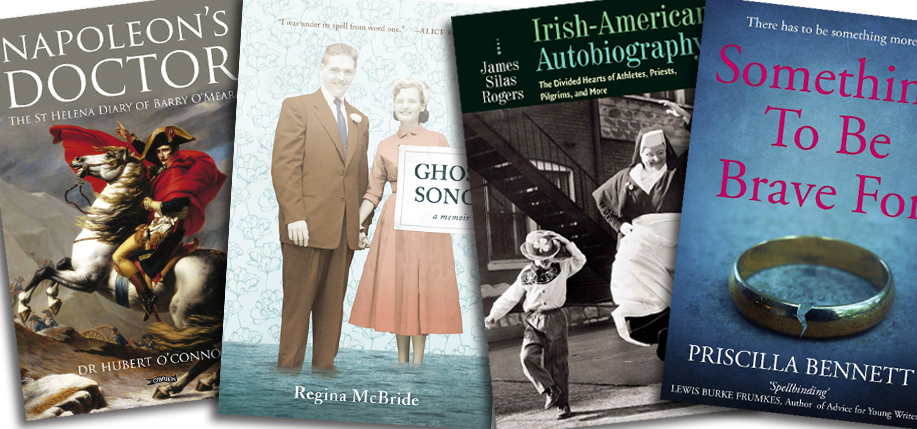

Recently published books of Irish and Irish American interest.

Napoleon’s Doctor: The St. Helena Diary of Barry O’Meara

By Dr. Hubert O’Connor

The last few years of the great Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s life were spent with an Irishman. That Irishman was Barry O’Meara, a Dublin-born surgeon who caught the Emperor’s attention during his surrender on the British warship Bellerophon. This encounter would change O’Meara’s life, as he was personally requested by Napoleon to be his physician during his time on the island of St. Helena after Napoleon’s original physician fell ill and begged his Emperor to be dismissed.

Napoleon’s Doctor: The St. Helena Diary of Barry O’Meara, by Dr. Hubert O’Connor, is a fascinating insight into one of the most influential military minds that the world has ever seen. The book is the result of 30 years of research by O’Connor, a former rugby player for Ireland and a physician himself. In it, O’Connor transitions between O’Meara’s diary and the history surrounding O’Meara’s words.

O’Connor had two goals in mind in researching and writing this book. He wanted to “attempt to vindicate the reputation of O’ Meara” and to “paint a personal picture of the Emperor and the Irishman – the great Napoleon himself on St.

Helena and the Irish doctor who accompanied him there.” These goals are admirably attained in O’Connor’s thorough project, as he mostly lets O’Meara’s diary entries do the work in showing how these two men interacted.

After the diary entries, O’Connor delves into the last days of Napoleon’s life, O’Meara’s return to London, and the journey Napoleon’s body took from St. Helena back to France. The last chapter explores the possibility of Napoleon being poisoned by his jailers at the end of his exile. If you want an intimate perspective on the last days of a man who almost conquered the world, Napoleon’s Doctor should be right up your alley.

– Dave Lewis

(O’Brien / 224 pp. / €16.99)

Ghost Songs

By Regina McBride

Ghost Songs, Regina McBride’s new memoir of despair and recovery, is a coming-of-age story set in the aftermath of her parents’ suicides as she attempts to navigate the chimeric burden and comfort of ancestral inheritance. “I am still a child when I find out that neither of my parents have actually ever been to Ireland,” she writes in one of the book’s flashback sequences. “I wonder how they can still love and miss a place their ancestors left before they were born. Yet somehow I

understand.” For McBride, the idea of missing a place to which one has never been represents a continuity with the past as much as it symbolizes its haunting of the present. It is in the space between these two nodes – the terror and the beauty implicated in the memoir’s title – that McBride sets to work rebuilding her life.

The memoir opens after McBride’s admission into a psychiatric ward after a breakdown following her parents’ closely-timed deaths as she documents her struggle with the literal ghosts of her past. This is not some metaphoric haunting, but the actual specters of her mother and father who pay her frequent, distressingly silent visits by night. Eighteen-year-old Regina confesses to her therapist that due to a relentlessly Irish American upbringing, she wrestles with the staunch Catholic belief that those who die by their own hand are damned to purgatory, trapped between the world of the living and the afterlife forever. Desperate to come to terms with the past and learn to cope with, if not move on from, her grief, Regina sells her car and buys a one way ticket across the Atlantic, searching for answers on the small island that was, for her parents, magnetizing but unreachable.

A dizzying network of memories new and old, Ghost Songs bears a title incredibly befitting of the narrative pattern it represents. At times, the novel composes itself from strings of vignettes and quasi-prose poetry, faithfully rendering the mindset of a narrator acutely displaced by her loss, whose consciousness snags on regret and things left unsaid at every turn.

Searching for solace in the land from where her grandparents emigrated, McBride becomes familiar with a new kind of Ireland – one decidedly her own, landmarked with moments of self-discovery and the realization that, after the storm is over and the wreckage cleared, that which has survived will provide the steadfast foundation needed to begin afresh.

– Olivia O’Mahony

(Tin House / 312 pp. / $15.95)

Irish-American Autobiography: The Divided Hearts of Athletes, Priests, Pilgrims, and More

By James Silas Rogers

The title, and especially the cover, of Irish-American Autobiography belie the content and message of this brilliant book. It’s not an autobiography at all – the author remains anonymous throughout, serving only as a narrator studying what it means to be Irish in America. While the cover features a traditional nun step-dancing with children wearing symbols of Irish treacle, leprechaun derbies, the book is anything but a sentimental trek through Irish eyes, smiling or crying. Rather, in Irish-American Autobiography James Silas Rogers brings an insightful and beautifully written study of Irish-Americana over the past 100 years.

The book is a series of essays that encompass biographies, literary excerpts, and countless cultural references to illustrate the disparate history of Irish immigrants and the generations that followed. Rogers covers all the tropes of the Irish-American experience, particularly immigration. He posits that assimilation, contrary to popular belief and despite the common language, was painful for Irish immigrants and their children: “the profound experience of being on the inside and on the outside in two different places.”

If there is an over-arching theme in the book, it’s that to be Irish means to be a study in contradictions, whether it’s Gaelic vs. English, cynic vs. happy-go-lucky or shanty vs. lace-curtain. As the Irish left the ethnic strongholds of the city (“peaceful ethnocide”), they moved to the sameness of the suburbs, becoming in effect, “deracinated.” Yet – contradiction again – the more the blood of Ireland became diluted in modern generations, the more they begin to embrace their Irishness.

“The heirs,” as Rogers calls them, “have invented an ethnic identity out of scattered knowledge… or nakedly constructed ones, such as ‘Kiss me, I’m Irish!’ buttons. It’s part of a particularly American need be ‘from somewhere.’” Why not embrace your Irishness, however minimal, and become a member of an impish and fun-loving race? To do this, of course, the heirs need to obliterate the tragic history of Ireland and its many brooding “priest-ridden” inhabitants.

The book gracefully moves from writers to accordion players, from John F. Kennedy to Whitey Bolger, from priests to heavy weight champions.

In a fascinating chapter, Rogers analyzes and contextualizes the bus driver from Brooklyn, Ralph Kramden, a figure familiar to all of us of a certain age. Ralph doesn’t have an Irish name but it’s clear he’s as Irish as his creator, the actor who plays him, Jackie Gleason. The Honeymooners is filled with Irish subtext – the long-suffering wife, the tiny tenement apartment where the Kramdens are “crammed in,” Ralph stuck in his working class job waiting for his lucky break, his pot of gold, to arrive. All that sadness under all that brilliant humor, so very Irish.

Rogers celebrates the recent shift in the mindset of Irish Americans. Thanks to the genealogy websites like Ancestry and 23andMe, many Irish Americans now visit Ireland, not to ride on jaunting cars or donkeys, but to search for their roots and visit the land of their ancestors. Called alternately “The Homecoming” or “The Gathering,” these modern pilgrims are now versed in Ireland’s bloody and starving history. They want to grasp what it means to be Irish, realizing that it’s so much more than green beer or buttons or leprechaun derby hats.

President Kennedy expressed this as far back as 1963 during his Ireland trip: “It is strange that so many years could pass and so many generations pass and still some of us who came on this trip could come home – here to Ireland – and not feel ourselves in a strange country.”

– Rosemary Rogers

(Catholic University of America Press / 208 pp. / $24.95)

Something to Be Brave For

By Priscilla Bennett

There can never be enough said or written about domestic violence. Too often it’s lurked in the shadows, silent, its victims muted by shame. Something to Be Brave For is an important take on this epidemic that claims 24 victims per minute and still hides only to emerge when a celebrity is involved or when an assault ends in death.

This novel brings domestic abuse into a rarefied strata of society where wealth, fame and plastic surgery intersect. The protagonist, Katie Giraud, is married to a world famous plastic surgeon who spends his days carving the faces of his adoring patients, and relaxes at night by battering the face of his wife. Katie tells no one about her terrible secret; who would believe a voice from a gilded cage? Priscilla Bennett, a former emergency room nurse and victim advocate, tells this Jekyll and Hyde story at a rapid and terrifying pace. The author has partnered with the National Network to End Domestic Violence in Washington, D.C., which will receive some of the proceeds from the sale of the e-book.

– Rosemary Rogers

(Endeavour Press, published exclusively for Amazon Kindle / 225 pp. / $3.99, or free with Kindle Unlimited)

Leave a Reply