My maternal grandmother Kate Whalen and I were very close. As a child, I would go to Jersey City to stay with her for two or three weeks during the summer. As I got older, she was as much a friend as a grandmother. Over the years, I learned bits and pieces of the story of her early years and wanted to know more. Many years later, I realized that my interest meant dredging up things she had deliberately left behind, and my curiosity may have caused her pain. Knowing what I now know, I am grateful she shared what she did and made possible my ensuing 30-year quest to discover more.

Kate, a redhead like her mother, was born in 1904 in Jersey City, the daughter of Mary Agnes Flannelly, known as Mamie, and Patrick Joseph Whalen. She was one of five children, three girls, and two boys. Pat Whalen, my great-grandfather, was born to Irish immigrant parents and raised by his widowed mother. He was a drinker and ne’er-do-well by all accounts. In 1913, Mamie died of tuberculosis at the age of 35; the disease had taken her only sister, Anna, four years earlier.

Pat enlisted in the Army, leaving the raising and care of his children to various relations.

A year after her mother’s death, Kate’s five-year-old sister had died after falling into a bonfire of leaves in the street, and Kate was being shuffled between her Irish aunts and uncles. Things did not go well for her with her Whalen and Flannelly extended family. By the age of 13, after running away from a severe aunt whom she blamed for her younger brother’s crippling fall down a flight of stairs, Kate went into domestic service in the home of a prosperous family in Jersey City Heights. She was paid $12 a month and remained there until, at 16, she married and embarked on a loving partnership that would last over 50 years until her death. Kate was a devoted mother to five sons and one daughter (my mother), a doting grandmother to 13, and a dear great-grandmother to my sons and cousins’ children.

While her difficult, interrupted childhood and subsequent premature leap into adulthood and the creation of a loving family made me proud of her, that childhood and the abandonment by her father were an embarrassment to her, one of those skeletons found in so many family closets. She knew next to nothing about her family history, believing that her parents were born in the U.S. of Irish immigrants, which turned out to be correct. I was determined to find out her greater family story, sure that I could dilute her painful childhood memories by doing so. She did not live to see me succeed, falling victim to Alzheimer’s in her early eighties. But I did succeed, albeit many years later.

So, who was my grandmother Kate?

Kate Whalen was the granddaughter of John J. Flannelly, born in 1841 in Skreen Parish, County Sligo. John and his five surviving siblings fled Ireland with their parents, William and Mary Lang Flannelly, in late 1846 during the Great Hunger. They sailed alongside 180 other Irish men, women and children in steerage class in the belly of the packet ship Marmion out of Liverpool, landing in New York on November 28, 1846.

They settled in downtown Jersey City among other Irish immigrants. William Flannelly, a Catholic born in about 1800, was the son of Owen and Mary Flannelly, who were born in the second half of the 18th century in the waning years of the Penal Laws. William’s wife Mary Lang, raised in the Church of Ireland, was born in about 1810 in County Cavan to John Lang of Killeshandra and his wife Abigail Leviston, descended of the Levistons of Cullentragh.

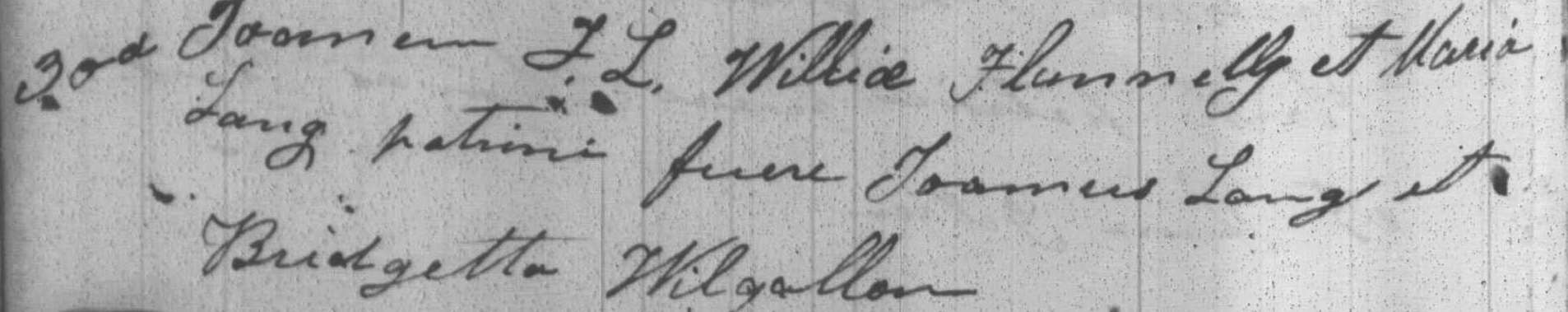

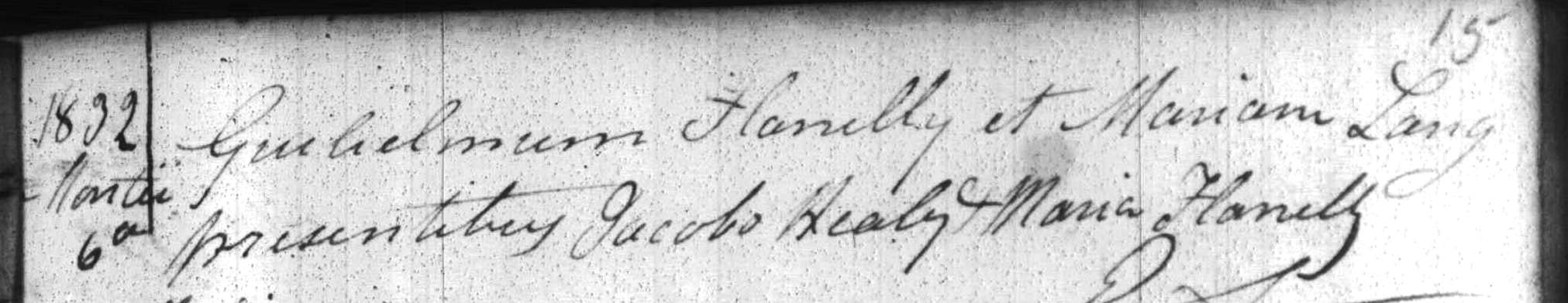

Mary turned away from her family and her Protestant faith and married William Flannelly in March 1832 at the Flannelly’s Catholic parish church in Skreen. She must have been a very strong young woman to defy convention and societal boundaries to marry the Catholic man she loved. She would need that strength 14 years later when she and William, then in his mid-40s and a tenant farmer on the lands of a Cromwellian plantation descendant named Jeremiah Jones, made the fateful decision to join the diaspora trying to escape the ravages of hunger.

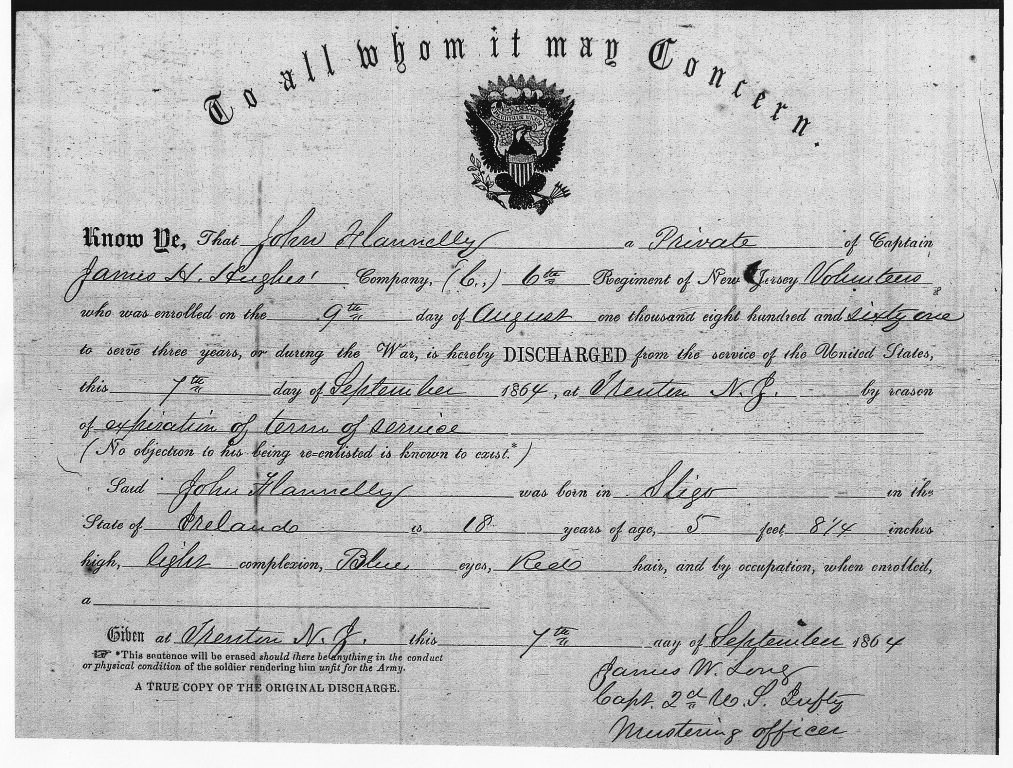

John J. Flannelly, age five when he arrived in America in 1846 with his parents and siblings, enlisted in the Union Army at age 18 in 1861, incentivized by the promise of a $100 bounty payment for three years’ service. In May, 1862, he fought on the front lines at the Battle of Williamsburg, Virginia, a place I would feel drawn to and visit regularly for over 30 years before the discovery of that personal family connection. John’s military service record shows he was hospitalized there post-battle.

As John lay in a Williamsburg field hospital, three thousand miles away, a 13-year-old Irish girl named Bridget Hough (but who everybody called Delia) had made her way to Liverpool alone and set sail on the ship Vanguard destined for America. Delia traveled in steerage along with 345 other Irish emigrants. The ship passenger manifest indicated she was a “housemaid,” one of 75 female steerage passengers aged 7 to 62 with that same occupational designation. In addition, another 41 women in steerage were listed as “servant,” meaning that more than one-third of the passengers in steerage were girls and women intending to go into domestic service upon arrival in America.

John Flannelly returned from the Civil War in 1864 and would meet and marry Delia Hough at the former St. Peter Church in Jersey City in October 1867. They had 10 children, two sons dying in infancy. The surviving children, six boys and two girls, included my great-grandmother, Mamie Flannelly. Delia died at 41 years old in 1890 of pneumonia and John, a Civil War pensioner, died in 1894 at age 53, leaving Mamie parentless at age 15. Just four years later, Mamie would become an unwed teenage mother and, in the 1900 U.S. census, is found as a boarder in a rooming house working in a local laundry as an “ironer” to support herself and her baby son, John Flannelly. At the age of 22 she married Pat Whalen. My grandmother Kate was born three years later.

The Flannellys had escaped the ravages of the Great Hunger by no doubt reluctantly leaving the homeland and family they loved. Their new life in America was a story of continuing struggle to integrate into the community, laboring like most immigrants in low-paying, physically demanding jobs and dealing daily with the challenge of keeping a roof over their heads and food on the table as tenants in row houses and tenements in crowded immigrant neighborhoods along the congested and increasingly industrial streets of downtown Jersey City in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Despite the family’s presence in America for a half-century by the time my grandmother was born, they lived in the same immigrant neighborhood and had not yet risen out of the lowest laboring class, nor escaped the threat of poverty.

I wish I could have held my grandmother’s hands in mine, telling her the story of her modest, persevering Irish family who risked everything and sailed across the vast ocean in a quest to survive. I wish I could tell her about her Irish immigrant great-grandparents’ “love match” that led to a 50-year marriage and about the parallel between her early teenage years in domestic service in Jersey City and those of her grandmother Delia some 50 years earlier. But the Alzheimer’s, like quicksand, had dragged her down to a cruel death years before I discovered her family story.

In recent months, television programs on NBC and PBS have generated renewed interest in genealogy, using the tag line “who do you think you are” and, in the course of 60-minutes, revealing the ancestral family history of various public figures including entertainers, film-makers and the like. I am pleased and proud to have answered that same question for my Kate and for me, realizing that my grandmothers Mary, Delia, Mamie, and Kate’s lives, woven of struggle, difficult choices, spiritual faith, and love of family made possible the gift of their ancestral DNA and my very life. ♦

Leave a Reply