This past March I traveled through Northern Ireland as part of a group of 19 students and administrators from New York University’s Gallatin School. We had come to Northern Ireland to gain a better understanding of human rights issues. What I gained an understanding of, however, was how large the gap had become between what I thought I knew and the reality of Northern Irish life.

Wandering Derry’s medieval walls, fellow group member Elizabeth Morrow and I stopped in front of a British Army surveillance tower that looked out over the nationalist Bogside community.

“This is unreal,” I said. “This is so wrong.”

Elizabeth thought for a moment. “You know,” she said. “The Army probably heard you say that.” As if on cue, the tower watchman waved to us.

Having been in Northern Ireland less than a week, we had not yet grown accustomed to feelings of being watched and of having to constantly watch ourselves.

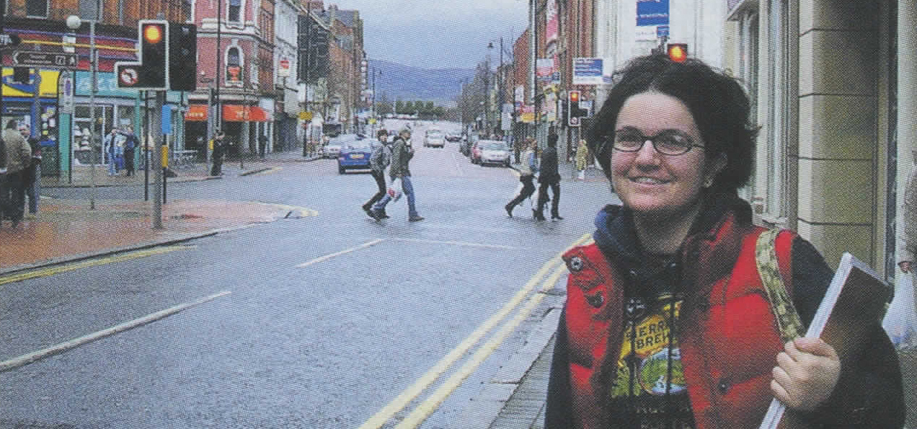

I have since graduated from NYU with a degree in Irish Literature, and my education in Irish Studies was excellent. However it did not teach me to decipher the subtle codes of political discussions, or how to reconcile my support for nationalist causes with my abhorrence of violence. On Shankill Road, the barrel of a rifle trailed me from a mural. A sound appreciation of colonial theory did nothing to ease my anxiety.

Another major issue for which my education did not prepare me was the depth of discomfort among the people of color in our group while in Northern Ireland. The tone was set by a local in Downpatrick. When asked what programs the town’s St. Patrick Centre offered for immigrants and minorities, we were told that the center did not offer programs for people of color. Minorities simply aren’t a factor in the community. Especially after learning of recent anti-immigrant violence in Belfast, the message for many people of color in our group was that they were not welcome.

Some of them came to Ireland prepared to feel this ostracism. Many of our members had already experienced racism from Irish-Americans. The fact that Irish-Americans have developed a reputation for being a particularly racist group is an issue that is rarely analyzed in our communities. My immediate reaction to this assertion was that I had never personally contributed to the problem, but perhaps I wasn’t being honest with myself. No matter how much Irish-Americans cling to our history as a colonized people, in 2004, we are part of the majority, and, possibly, part of the problem.

Perhaps we should take to heart the experience of Gallatin administrator Jigna Bhagat. A woman of Indian heritage, Jigna was among those who felt uncomfortable in Northern Ireland. In Derry, however, we learned of the struggle of dissenters imprisoned by the British. Many experiences of Northern Irish political prisoners are similar to those of Indian political prisoners, such as forced feeding while on hunger strike. This link between being Indian and being Irish came as a revelation to Jigna. “I could never again see Irish people as simply white,” she said.

What alarmed us most about Northern Ireland was the hyperpoliticized atmosphere. We visited Derry’s Bogside and stood where Bloody Sunday had occurred. On St. Patrick’s Day, a car bomb planted by loyalists outside a nightclub near our hostel in Belfast was discovered and detonated by security services. No one was harmed, but the proximity was frightening. It was also exhilarating — an admission that shames me. This suffering, these life-defining politics, is what we demand from Ireland. Political strife and struggle have always been Irish exports for American consumption. The ability to escape from it is one of the factors that make us Irish-American, rather than Irish.

Returning to Dublin was a major shift in tone; despite the rhetoric that the island is a unified entity, it was clear that the Republic was happy to be far from the North’s turmoil, culturally if not physically. On a late night cab ride from the Brazen Head pub, I told the driver that we had been in Northern Ireland, and asked him what people in the Republic thought of the situation. In the universally blunt style of cab drivers he said, “Ah, we don’t give a shit.” Though a single comment cannot speak for an entire nation, his contented disconnect evidenced that the distance between Derry and Dublin was far greater than mere kilometers.

In Belfast’s Crown Liquor Saloon, I spoke with a local man about life in the city since the Good Friday Agreement. At the end of the night, he leaned over and whispered in my ear. “No one’s dying anymore,” he said. “That’s the victory.” ♦

You were in a country not your own. Your take on the Irish and Irish Americans saying they all tend to be racist. It really is none of your business what the N.I. feel about people of color after all they have enough trouble as Catholics trying to be accepted then having you preach how or why they don’t welcome others. As for Irish American as you say are known for being against blacks don’t paint people with the same brush. Sometimes the most educated are lacking good old common sense.