In antebellum Georgia, the Healy children, born legal slaves to an Irish immigrant father and his black common-law wife, had to be smuggled out of the state to avoid being sold into slavery. Several would go on to become some of the first mixed-race high-ranking members of the Catholic Church.

Nineteenth century Georgia saw a remarkable phenomenon called the Healy family. The father was an Irish immigrant turned wealthy Georgia landowner. The mother had been his mixed-race slave. Their common-law union produced two nuns and three priests. Among them were: the first American priest and bishop of black descent, the first American Jesuit and Ph.D. of black descent, and the nation’s first Mother Superior of black descent.

Their father, Michael Morris Healy, was born on September 20, 1796. For some reason, he claimed to have been from County Galway, but his background was traced to Roscommon. He left Ireland in 1815 and, after entering the U.S. through New York he came to Augusta, Georgia, before settling in rural Jones County, Georgia, in 1818.

By means of persistence, good fortune, and the labor of slaves, he became wealthy. He would have had considerable prospects, but he never married – at least not legally. Rather, he entered into an unofficial marriage with one of his slaves, Eliza Clark. Her birthdate is uncertain but she was considerably younger than him: they likely began their relationship when she was in her late teens and he was in his mid 30s.

Though many landowners had physical relations with their slaves, it was unusual for a successful planter to make a slave his significant other. As to why he chose such a relationship, the most likely reason was that he genuinely loved her. And so their ongoing, committed, interracial relationship “violated perhaps the most powerful taboo of 19th century America,” as related by James M. O’Toole’s book Passing for White: Race, Religion, and the Healy Family, 1820-1920.

As noble as Healy’s affection may have been, the children of this union – ten in total, nine of whom survived to adulthood – would face a heavy burden. First and foremost, they were legally born slaves. The laws of Antebellum Georgia were stacked against people with any known or discernable degree of black ancestry. If a mother was a slave, her children were slaves, too. End of story. It didn’t matter if they had majority white blood.

Healy could not legally grant freedom to his own children. In fact, he technically could have been prosecuted for teaching them how to read. The Irishman knew that if his biracial children were going to succeed in life, he had to get them out of the 1830s South.

So, to the North they were sent. The elder children first attended a Quaker school in Flushing, New York. Several years later, four of the Healy brothers had enrolled at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and two Healy sisters were attending schools in New York City. The Healy children were good, eager students, finishing either at or near the top of their class. Having made it North, they stayed there. Time off from school was spent at the homes of the extended families of the priests they knew.

Following the January 1849 birth of the youngest child, Eugene, the Healys planned to relocate the whole family to the North. But this move never took place. Eliza Clark Healy – slave, mother, and unofficial wife – died on May 19, 1850. She was still young, most likely not even 40. The cause of her death is at this point unknown. Barely three months later, her former owner and heartbroken widower, Michael Morris Healy, followed her into the grave at age 53.

With both parents gone, one of the elder Healy sons, Hugh, headed down to Georgia – at great personal risk to himself (for he was technically a fugitive slave) – to rescue his younger siblings, who were especially vulnerable as both orphans and slaves. The rescue mission was a success, and all the Healys made it out of Georgia.

After graduating first in his class at Holy Cross, James Augustine Healy, the eldest son, entered a seminary in Montreal. He then relocated to Paris, where he was ordained in 1854. Returning to Boston, he served as a priest there for two decades and tirelessly worked with the city’s growing population of poor immigrants, most of them Irish. He was consecrated as the Bishop of the Diocese of Portland, Maine, in 1875. During his tenure as bishop, his diocese added more than 60 parishes and 18 schools and convents.

Upon graduating from Holy Cross, Patrick Francis Healy entered a Jesuit order. While in Europe, he earned a Ph.D. and was ordained to the priesthood in 1866. Returning to the U.S., he taught philosophy at Georgetown University, before becoming the school’s 29th president. His accomplishments for Georgetown were such that, according to BlackPast.org, he is often referred to as the school’s “second founder.”

After she was orphaned at age four, Eliza Dunamore Healy lived with her older brother, Hugh, in New York City. On reaching adulthood, she entered a convent in Montreal. Upon having spent decades teaching at several Canadian schools, she was appointed Mother Superior of a convent in St. Albans, Vermont. She ended her days at the College of Notre Dame on Staten Island, New York, where she died in 1918.

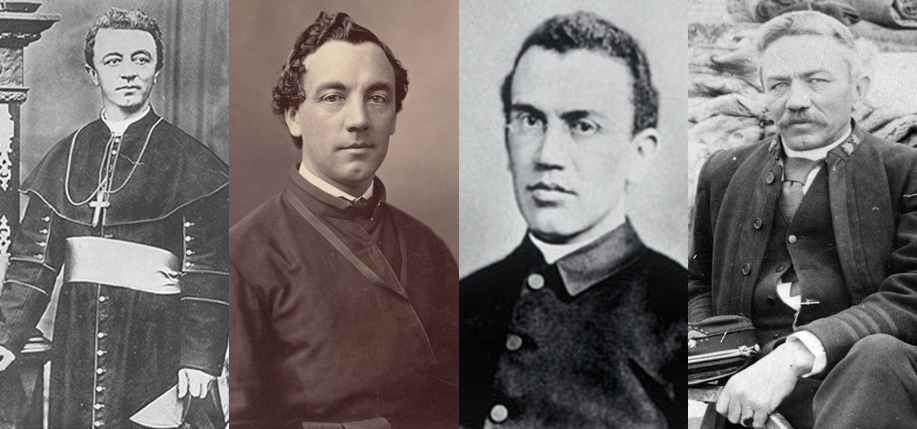

The only surviving Healy photographs are of four sons. Their complexions range significantly: Patrick Francis Healy, S.J., looks like an Irish Jesuit. However, Alexander Sherwood Healy – who served as a priest in Boston and well might have been consecrated as a bishop had he not died at age 39 – has visible mixed-race ancestry. And of indeterminable ethnic appearance is Michael Augustine Healy, the most successful of the children who did not enter the religious life; he became the first officer of black descent in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, the predecessor to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Most of the Healys were viewed as white, and official documents, such as death certificates, denoted them as such. When Mary Healy Cashman – an ex-nun who became a wife and mother – died on May 18, 1920, it brought the close to a remarkable generation made possible when, just over 100 years earlier, an Irish immigrant staked his claim on the Georgia frontier. ♦

_______________

Ray Cavanaugh is a freelance scribe from Massachusetts. His mother comes straight from Kerry, and his father is a few generations removed from Wexford.

The most important thing to remember is that the Healy siblings were proud to be IRISH-AMERICAN and should never be presented as black or African American. They were considered white and Irish and none of their achievements could have been duplicated by blacks of that period.

When Are Irish-Americans Not Good Enough to Be Irish-American?

“Racial Kidnapping” and the Case of the Healy Family

https://medium.com/@mischling2nd/when-are-irish-americans-not-good-enough-to-be-irish-american-71426efc247d

When my eldest son was about five, my wife decided we ought to send him to Sunday School which might have been too early for him. He came home in tears. He’d never heard group singing before and when the class started a hymn, the lyrics of which he’d never heard, he bleated out sounds “dah, dah, dah,” unrelated to the melody and the teacher snapped at him, “Shut up.” We lived in Queens, NY at the time. A few days later, out for a walk, we ran into a couple of Irish girls my wife had met before. They were about ten or twelve. My wife asked them about their school, and my son piped up, “I went to school! One of the girls said, “You’re too young for school.” My explained to them that he meant Sunday school. The girl asked, “Where did you go?” He pointed and said up there on the hill.” The girl said, “Then you must be a Protestant” and he angrily replied, “No, I’m a boy.” That line hit me like a ton of bricks.

I used that line many years later when I wrote a screenplay titled THE AMERICAN HEALYS. There was very little information on them at the time. It took a lot of research. A friend of mine lived next door to the late Cardinal Carter in Toronto, and he provided an introduction to the Superior at Notre Dame in Montreal where one of the Healy girls studied who became a superior herself later on, and they provided a ton of copies of correspondence between her and the Bishop, then in Maine.

In the screenplay I had to fill in scenes concocted by conjecture and in one of them I had a horse trader come to Healy’s plantation with some horses. He brought his young son along and young James took him down to the creek to catch polliwogs. Eliza Healy comes out to the porch to call down to the boys not to get themselves muddy, and the visitor boy, surprised to see that she was black, says to James, “If that be your mama then you must be a nigger.” Little James retorts, “No, I’m a boy.”

I’m neither Black or Irish or Catholic, but as I did my research and wrote that screenplay, I became all three. They were a beautiful family.

It’s a shame that there blackness had to be denied in order to achieve success. There is nothing wrong with being Irish American BUT there there is also absolutely nothing wrong with them equally being African American. Their mother’s life mattered, especially to their father

The children THEMSELVES identified as “white Irish”. AND 3 of 4 grandparents you’d call “white” vs 1 of 4 “black”, so why is it MORE accurate to call them “black” & to disregard 75% of their family??

And how is it up to everyone else to re-label them contradictorily to their own wishes, long after their deaths & pretend as if to know who they are better than the children themselves?? And by prejudicing the 1 “black” grandparent over the 3 other “non-black” ones??

Seeing as none of them nor their parents ever said there was anything wrong with being “black”, I’m not sure what that argument is in aid of…??

Did any of the children have kids? I suspect the majority entered the priesthood/nunnery and could not marry.

I was surprised that Michael Healy is not mentioned here. He was a famous Coast Guard officer and has a CG Cutter named after him.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_A._Healy

Historically, when you are part black, you are not good enough to be Irish American, in fact your not good enough to be a lot of things. Those are the unwritten rules. Fortunately, those rules were made to be broken.

It seems only two of the children married. Son Michael Healy married Mary Jane Roach and they had a son Fred.. Daughter, Martha Healy, married and Irishman, Jeremiah Cashman, they had a daughter Elizabeth.