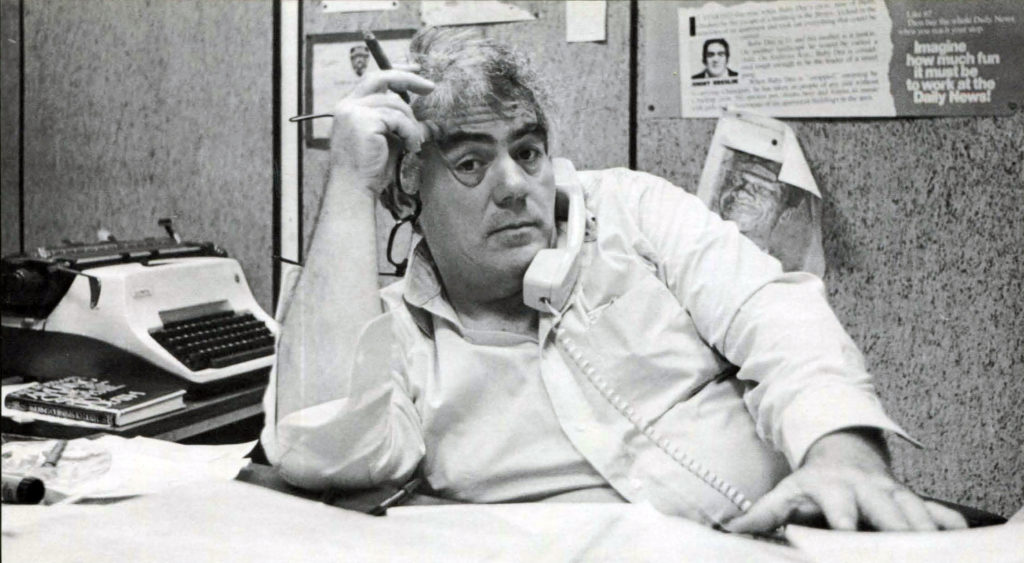

Jimmy Breslin

1928 – 2017

Legendary New York City reporter Jimmy Breslin, who appeared on Irish America’s second ever cover in January of 1986, died March 19 in Manhattan following a bout of pneumonia.

Breslin had a knack for finding the overlooked characters on the periphery of major stories. He wrote columns on the gravedigger for John F. Kennedy’s plot at Arlington who made $3.01 an hour; a single man, David Comacho, to document the AIDS crisis in the city in the 1980s; the scene in the kitchen when Robert F. Kennedy was shot. But he also took on the big guy, picking fights with figures and institutions as far ranging as New York Governor Hugh L. Carey, whom he took to calling “Society Carey,” to the Catholic Church.

Born James Earl Breslin October 17, 1928, and raised in the Richmond Hill section of Queens, Breslin’s grandparents emigrated from Clare and Donegal. In 1985, the Village Voice called him “classic black Irish, he loves conflict and he acts like each day is the worst day of his life.” Breslin honed a brash wit and descriptive writing style that became known as New Journalism throughout the 1960s and early ’70s, though Breslin himself rejected the term. His writing, he said, was a combination of Dickensian narrative and the visual description necessary for sports reporting, where he got his start as a copy boy at the Long Island Press in the 1940s. He would go on to write for the New York Journal-American, the New York Herald-Tribune, Newsday, and both the New York Post and Daily News, the latter where he spend the majority of his career.

Writing for the New York Times, columnist Dan Barry recalled the impact Breslin had on his younger writing. “When I was a kid, my father would say: Read Breslin today. Never: Good morning. Never: I love you. Just: Read Breslin today,” he says. “The advice was good – and bad. Good because I got to read the prose of this journalistic genius, Breslin. Bad because, like so many other young reporters, I developed a Breslin tic.”

In Irish America’s 2010 Famine issue, we published a piece of Breslin’s called “Leaves of Pain,” originally written in 1977, that weaves from the Fairlow Herbarium in Cambridge, Massachusetts through the Famine, the 1863 Draft Riots (though at the time they took place they were known as the “Irish Riots,” Breslin noted), and ends with the murder and funeral of a friend in the do-or-die Bed-Stuy neighborhood of Brooklyn in New York’s bankrupt ’70s. The piece barely breaks 1,500 words. (You can read this and our 1986 interview with Breslin at irishamerica.com.)

Interviewed for Irish America in Costello’s bar in New York (a second home for Daily News journalists) in 1986, Breslin offered a succinct description of what makes him so prolific: “Writing is not a business you talk about much, or covering things is not a business you talk about much, for mostly anything you know you should put in the paper. That’s about it.”

Breslin is survived by his wife, Ronnie Eldridge, a former Manhattan city council member, four sons, Kevin, James, Patrick and Christopher; a stepson, Daniel Eldridge; two stepdaughters, Emily and Lucy Eldridge; a sister, Deirdre Breslin; and 12 grandchildren.

– Adam Farley

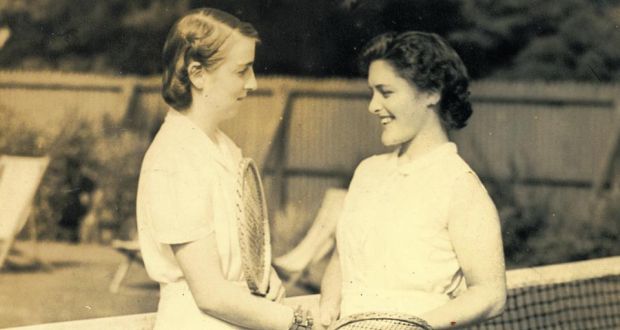

Rena Dardis

1924 – 2017

Katherina “Rena” Dardis, founding member of Anvil Press and The Children’s Press, died in March at the age of 93. Economical and inspired, Dardis was among the first publishers to consider her authors as public figures, helping them establish relationships and rapport with their readers at libraries and launch events for success.

Born in County Kilkenny to a Westmeath father and mother from Donegal, Dardis lived in her childhood home in Rathmines, Dublin with her sister, Margaret, until 2009. She first worked in advertising with Guinness, though quickly moved on to become a respected writer and director at the O’Kennedy Brindley advertising firm. She was president of the Institute of Creative Advertising and Design from 1969 to 1970.

In 1962, Dardis founded Anvil Press with Seamus McConville and Dan Nolan (her life partner) of the Kerryman, reprinting many books on the Irish War of Independence, including Rebel Cork’s Fighting Story by Ernie O’Malley in a run of 10,000 as well as many new novels. Dardis established The Children’s Press, one of Ireland’s first publishing houses for children, in the early 1980s. In 1996, she received the Children’s Books Ireland Award for her contribution to children’s literature in all genres and age brackets.

Remembered as “honest and forthright, considerate and generous” by Tom McCoughren, author of In Search of the Liberty Tree (which Dardis published), she is survived by her partner, Dan.

– Olivia O’Mahony

William Liebenow

1920 – 2017

Decorated WWII naval lieutenant William “Bud” Liebenow, who was best known for leading the rescue party that saved the life of future 35th president of the United States John F. Kennedy when his patrol torpedo boat was attacked by Japanese forces, died in North Carolina in March. He was 97. Kennedy’s gratitude to Liebenow was lifelong, and he issued him a personal invitation to the president’s inaugural ball in 1961.

Liebenow first met Kennedy in 1941, while both trained for naval duty in Narragansett Bay, and were likewise both put in command of vessels stationed near the South Pacific’s Solomon Islands. A devastating attack by four Japanese ships on August 1, 1943 destroyed Kennedy’s ship, taking two lives and critically endangering the remaining ten. The crew rallied, swimming three miles to a nearby island. There, the crew met indigenous Allied scouts Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana, who relayed Kennedy’s SOS to a U.S. base, which had presumed him and his men dead. Soon after, Liebenow and the crew of the PT-157 arrived on shore and successfully ferried them to safety.

“We had quite a celebration going back,’’ Mr. Liebenow said in a 2005 interview with the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Dorchester. “The pharmacist’s mate handed out all the medical brandy.”

Liebenow’s illustrious naval career continued into 1944, when he commanded the PT-199 in rescuing 60 survivors of the U.S.S. Corry, the lead destroyer of the Normandy Invasion task force, after a German strike. In the autumn months of the war, he provided passage on his vessel for both the soon-to-be 34th president of the United States General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Normandy invasion leader General George S. Patton.

Liebenow was born in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and is survived by his wife, Lucy, children, Susan and William II, and two grandchildren.

– Olivia O’Mahony

Martin McGuinness

1950 – 2017

Martin McGuinness, Northern Ireland’s former deputy first minister and one of the primary architects of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, died March 21, at Derry’s Altnagelvin Hospital at the age of 66. McGuinness was diagnosed with a rare genetic heart disease in December and resigned amid health concerns as deputy first minister earlier this year, bringing about Northern Ireland elections, which saw Sinn Féin gain seats in Stormont.

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness was born May 23, 1950 in the impoverished segregated Catholic neighborhood of Bogside, where much of the Northern Irish civil rights movement took place. One of seven children, McGuinness was raised a devout Catholic and was an interested student, though at the age of 15 he dropped out of a Christian Brothers school, where he was beaten, to become a butcher’s apprentice. By the age of 18, he was a gunman in the IRA and by 21 was second in command of the Provisional IRA and a member of the IRA’s Army Council. (He often quipped that he was a graduate of UCB, University College Bogside.)

McGuinness joined the IRA after the failure of civil rights marches to bring about change. Having witnessed the violence in Bogside his entire life, he believed at the time that there were no peaceful means of negotiating with the British, especially after Bloody Sunday in January 1972, when civil rights marchers were gunned down in the streets of Derry by the British Army. McGuinness consistently denied allegations that he directed terrorist activities, and his only criminal convictions during the Troubles were for belonging to the IRA and possession of explosives and ammunition in 1973 and 1974.

By the early 1990s, McGuinness had become Sinn Féin’s head negotiator in the peace process and a primary force behind both the 1994 ceasefire and the Good Friday Agreement, which ended decades of violence in the North when it was signed on April 19, 1998. He was elected to the House of Commons in 1997 and the Northern Ireland Assembly in 1998 when the body was established. From 1999 to 2002 he served as education minister and in 2007, led Sinn Féin into power sharing with the Democratic Unionist Party and served as deputy first minister alongside Ian Paisley, Peter Robinson, and Arlene Foster until his retirement this January.

In 2001, McGuinness sat down for an interview with Irish America in which he reflected on his role in the IRA and the peace process. “I think that anyone who has a conscience has to wrestle with it and rationalize and decide how to live their own life. In the course of the late 1960s we lived through a very determined effort by the British government to defeat the battle for equality, justice and civil rights,” he said. “I think what drives me on more than anything is being very, very conscious that I am going forward with the hopes of 25,000 Mid-Ulster voters. People place so much hope in their political leaders, to make sure they get equality and justice and peace.”

He is survived by his wife, Bernie, whom he married in 1974, and their four children, Fiachra, Emmet, Fionnuala, and Grainne.

– Adam Farley

Thomas Starzl

1926 – 2017

Surgeon and researcher Dr. Thomas Starzl, called the “father of modern transplantation” by his contemporaries, died in March at the age of 90. Starzl performed the world’s first successful human liver transplant in 1967, later conducting research that immensely heightened organ transplant survival rates.

Born in Le Mars, Iowa to science fiction author Roman Frederick Starzl and Irish teacher and nurse Anna Laura Fitzgerald, Starzl intended to become a priest until his mother’s fatal battle with cancer in 1947, when his outlook shifted drastically. He obtained his medical degree at Chicago’s Northwestern University, where he developed a strong interest in liver biology, and in 1962 became a teacher and researcher at the University of Colorado in the then-embryonic field of organ transplantation. In 1963, his first attempt at a human liver transplant resulted in patient fatality. After four years of continued research, he operated successfully on a 19-month-old girl suffering from liver cancer, prolonging her life by one year and paving the way for future improvements.

“He showed persistence when everything else looked hopeless,” said chairman of the surgery department at the University of Nebraska Dr. Byers Shaw Jr., who operated alongside Starzl at the University of Pittsburgh in the 1980s.

Starzl had a lifelong fascination with his Irish heritage and, after giving the Sylvester O’Halloran Surgical Lectureship of the Irish Royal College of Surgeons in Limerick in 1997, visited his ancestral hometown of Clonbullogue, Co. Offaly.

In 1999, the Institute of Science Information named Starzl the world’s most-cited researcher, and in 2010 the Wall Street Journal ranked his autobiographical memoir, The Puzzle People, the third-best account of a doctor’s life. He is predeceased by two children, Thomas and Rebecca, and survived by his wife, Joy, and son, Timothy.

– Olivia O’Mahony

Leave a Reply