Geoffrey Cobb writes about Thomas Crawford, who sculpted the figure of Liberty and Freedom on top of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC.

People around the world recognize the massive, iconic statue of freedom majestically standing atop our nation’s capitol building in Washington, D.C., yet few people know that a New York Irish American, Thomas Crawford, created it. Crawford has not only been largely forgotten by history, but even his grave in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery lacks a headstone. This great, but forgotten Irish American artistic genius, however, deserves remembrance.

Crawford, born in New York City in 1814 of Irish parents, came of age at a time when young artists had few chances to train, but he was lucky enough to receive the best training the young country could offer an aspiring sculptor. Crawford, apprenticed at first to a wood carver, had the opportunity to master drawing by studying plaster casts at the newly created National Academy of Design and The American Academy of Fine Arts. At age 18, he was fortunate enough to apprentice under Robert Launitz, a New York-based Latvian sculptor, carving mantelpieces and architectural ornaments. Recognizing Crawford’s talent, Launitz arranged for him to study in Europe.

In 1835 Crawford set off for Rome, the city the artist would call home for the rest of his life. Writing to Launitz, Crawford gushed:

“Rome is the only place in the world fit for a young sculptor to commence his career in. Here he will find everything he can possibly require for his studies; he lives among artists, and every step he takes in this garden of the Arts presents something, which assists him in the formation of his taste. You can imagine my surprise upon seeing the wonderful halls of the Vatican – after leaving Barclay Street [then home to the American Academy] and the National [Academy of Design]. Only think of it a green one like me, who had seen but half-a dozon [sic] statues during the whole course of his life – to step thus suddenly into the midst of the greatest collection in the world.”*

In Rome, Crawford trained with the Danish-born Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770 – 1844), the preeminent neoclassical sculptor of the age. By the late 1830s, thanks to Thorvaldsen, Crawford’s talent had blossomed, moving beyond the unimaginative portrait busts of his early career into the realm of graceful, imaginative, ideal compositions.

Crawford’s first marble masterpiece, “Orpheus,” created in 1839, signaled to collectors back home his emergence as the premier American sculptor. His patron, Charles Sumner, Boston’s future United States Senator, arranged to show “Orpheus” and five other works in the first show ever by an American sculptor in 1844.

Although Crawford married into New York’s wealthy and influential Ward family, major commissions still eluded him. However, the commissioned pieces he did execute are considered masterpieces. He sculpted his beautiful “Genius of Mirth” in 1842 and four years later his stunning “Mexican Girl Dying,” which is a part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection. Nevertheless, Crawford still struggled to gain exposure and acceptance in the land of his birth.

In 1849, while on a visit home, he received his first big American commission for a monumental series of sculptures in the George Washington Memorial in Richmond, Virginia. He immediately returned to Rome and designed a star of five rays, each one of these to include a statue of historic Virginians, including Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson. At the center of the star rose an imposing equestrian statue of George Washington. His creation was hailed as one of the finest American sculptures ever executed.

In 1853 Crawford received his biggest commission. Captain Montgomery Meigs, supervising engineer of Capitol construction in Washington, D.C., asked Senator Edward Everett to recommend artists for the new pediments on the Capitol’s east front, and Everett suggested Crawford. Meigs wanted classical, symbolic sculptures for the pediments similar to the Parthenon in Athens and Crawford designed such a marble classical pediment, depicting scenes from early American history, called “The Progress of Civilization.” The pediment features a female America, who stands with an eagle at her side and the sun at her back. On the right, a woodsman, hunter, and Native American chief, mother, and child represent frontier America. On the left Crawford depicted various trades including a soldier, merchant, the two youths, the schoolmaster and child, and a mechanic. Completing the side of the pediment are sheaves of wheat, symbols of fertility, and an anchor, representing hope.

Crawford finished the drafts in 1854, but it took four years from 1855 to 1859 to sculpt the eighty-foot-long pediment. The figures he created were all freestanding, three-dimensional statues, independent of one another. Intricate details like the mechanic’s rolled up sleeves, and the well-dressed schoolmaster with his arm around a young pupil, proclaim Crawford’s consummate attention to the smallest details.

Crawford’s amazing ability to create intricately detailed three-dimensional figures also shines in his masterpiece bronze doors at the entrances to the House of Representatives and the Senate. The huge house doors, measuring over fourteen feet high and seven feet wide, were designed from 1855 to 1857, but they were only executed during the Civil War and not hung until 1905. The House of Representatives’ right door depicts various scenes from the Revolutionary War, while the left one depicts political scenes from the struggle for independence. The Senate doors also depict scenes of the revolution and the laying of the Capitol’s cornerstone, as well as Washington’s first inauguration and other democratic milestones.

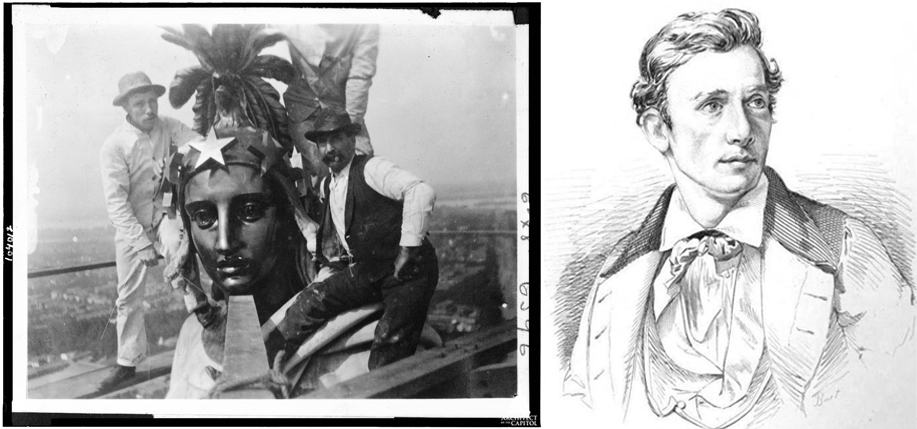

Crawford’s greatest design, a massive bronze standing figure almost twenty feet tall, weighing approximately 15,000 pounds, would stand atop the Capitol, but also generate fierce protests by slave owners. Originally, the plans for the figure atop the dome called for a statue representing the goddess of liberty, but Crawford instead proposed an allegorical figure of “Freedom Triumphant in War and Peace.” Crawford’s design was accepted in 1854 and during that same year he sculpted the plaster model for the statue in his Roman studio. U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who a few years later would become President of the Confederacy, headed the Capitol building project and held a veto over the statue’s form. According to David Hackett Fischer in his book Liberty and Freedom, Crawford’s statue was quite close to Davis’s ideas, except above the crown where New York Abolitionist Crawford had added a liberty cap, the old Roman symbol of an emancipated slave. This made the slave-owning Davis explode with rage, and Davis angrily demanded its removal. Crawford instead designed a military helmet, with an American eagle head and crest of feathers. Even Davis had to admit the unique beauty of Crawford’s elegant design. No other artist had done as much to grace the Capitol, but tragically Crawford would not live to see his designs realized.

In 1856, at the height of his artistic powers, and finally achieving success, Crawford’s sight began to deteriorate rapidly. He sought medical treatment in Paris, and physicians discovered cancer of the eye and cancer of the brain. Desperate, Crawford agreed to undergo an untested medical treatment that destroyed the eye and orbital contents. He died five months later in London on October 10, 1857 at age 44, never seeing any of his Capitol sculptures. His body was returned to the United States, and buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

There is a wonderfully ironic turn in the story of the “Freedom” statue. After Crawford’s death, the model for the statue was sent from Rome to Washington. The pieces of the massive sculpture had been bolted together, but when it came time to cast it, nobody could find a way to separate the parts, so they could be moved to the foundry. A slave working for his master’s foundry, Phillip Reid, figured out how to use a pulley and tackle to lift up the model and cast it. Reid worked seven days a week casting the massive figure, but the foundry owner took the money for six days of Reid’s week of work. Reid, however, saved the money from his one day of pay and used it to purchase his freedom; casting the allegorical “Freedom” helped Reid gain his own material freedom, which must have greatly pleased Crawford in heaven.

_______________

*Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825-1861. Eds. Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 167.

Geoffrey Cobb is a Brooklyn high school history teacher and the author of Greenpoint Brooklyn’s Forgotten Past (CreateSpace, 2015).

Hi all at Irish American.

Ken Murray here in Co. Meath Ireland.

I’m working on a book about the Irish who changed the World and sculptor Thomas Crawford has come up on my radar.

Would anybody happen to know what part of Ireland his parents were from?

If you know or can recommend a suitable source I can contact, pleaselet me know.

Many thanks.

Ken

HI Ken,

I just learned that he was not born in America, but was actually from Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal