The Irish language has roots stretching back at least 5,000 years and shares words with Sanskrit, the ancient classical language of India.

Almost all of us can speak a little Irish and often do. Words like “galore” and “brogue,” for example, or “smithereens” have all passed directly from Irish into English, often with little change to their original pronunciation.

So the next time you refer to a “banshee” or your “clan,” or the next time you sip a glass of “whiskey” – three more words that have made the linguistic leap from Irish to English – it’s worth noting that you’re actually using language that would have been comprehensible to the average person in an Irish village hundreds of years ago. Maybe even further back and much further afield too – the Irish language actually has roots stretching thousands of years into the past and a back story that links it with several European languages, and perhaps surprisingly, even some from much further afield.

The roots of modern Irish lie ultimately in a language spoken approximately 5,000 years ago in the area between the Baltic and the Black Sea. Known as Indo-European, this language is purely conjectural in the sense that no concrete evidence of it is extant, but using similarities between ostensibly unrelated languages (for example, the word “horse” is capall in Irish, caballo in Spanish, cheval in French, and cal in Romanian), experts have been able to surmise their derivation from a common ancestor.

The development of trade aided the gradual dispersion of Indo-European culture across the continents and the language became a forerunner to many modern language families. Among its descendants are the Germanic (Norwegian, Dutch, and German), Romance (Italian, French, and Spanish), and Slavic (Russian, Yugoslavian, and Bulgarian) tongues, as well as Hindi, and other languages spoken today in the northern India region.

The Celtic group of languages, which includes Irish, is also a descendant of Indo-European. Celtic is thought to have separated definitively from the parent tongue by 1,000 B.C. Over time, three distinct dialects of Celtic emerged – Gaulish, Brythonic, and Goidelic. Gaulish Celtic ceased to develop after the spread of Latin with the Roman Empire, but in the furthest reaches of the Empire, the Brythonic and Goidelic strands survived. The Brythonic dialect of Celtic gradually developed into Welsh, Breton, and Cornish, with Goidelic becoming the source of Scots, Manx, and Irish.

Brythonic and Goidelic differ from each other roughly as much as do the Romance languages French and Spanish. The most prominent feature distinguishing the Goidelic – or Gaelic – dialect is its use of the hard q-sound, as compared to a p-sound in the Brythonic. Thus, while surface similarities between Irish and Welsh or Breton appear limited, when the split between P and Q is considered, the connection between the two strands becomes clearer: the Irish word ceann, “head,” is penn in Welsh, and the Irish cuig, “five,” is pemp in Breton. Ireland’s isolated position ensured minimal external influences on Gaelic, and for centuries the language developed largely along its own path. Until the arrival of Christianity in the country, there was no written literary tradition apart from the cumbersome and necessarily limited ogham, which consisted of a series of markings carved into strategically placed standing stones. The first examples of written Irish came only with the arrival of Christian missionaries and monasteries.

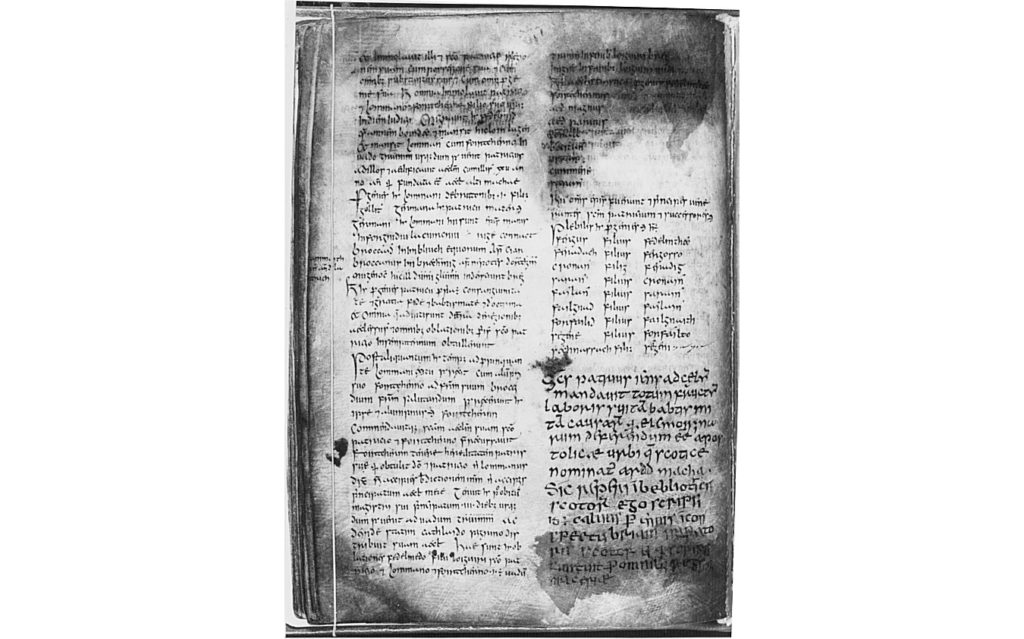

During this Early Literary Period (A.D. 600 to 900), learned men wrote almost exclusively in Latin, but a comparative study of the Irish of the time is made possible through the use of glosses, notes written in the margins of manuscripts explaining Latin words and their Irish equivalents. Some linguists believe it likely that the vernacular and the written forms of the Early Literary Period were effectively separate languages.

The first Viking raids in 795 marked the beginning of a new era for the language as loanwords began to appear from the Norse, Welsh, and Latin, and written language became more like that of everyday speech. A less rigid grammatical structure developed in the Middle Irish Period (A.D. 900 to 1200), and while largely incomprehensible to non-experts, snatches of Irish from this time can be understood by modern speakers in the same way that fragments of the epic poem “Beowulf” might be understood by modern English speakers.

During the Classical Period (A.D. 1200 to 1600), Irish became a language under threat. In 1169, the Norman invasion of Ireland began, and the armies that arrived in the country were a linguistically mixed lot, consisting of not only the Normans themselves, but soldiers from the southeast counties of England Welshmen, and Flemings. Indeed, with the arrival of the Normans, the Irish language was, for a time, faced with two main rivals in the country – English and French. The latter was the language of the ruling classes and important churchmen, with English spoken by the ex-soldier tenants of the landed rulers.

Irish remained the vernacular of the majority of the population, however, and as the use of Norman French by ruling lords declined, the indigenous language began to take its place. This gaelicization of the Anglo-Normans was perceived as a threat by the English, and many subsequent attempts were made to stamp out Irish; in 1367, the Statutes of Kilkenny made it a crime for an English person to speak Irish, have an Irish name, or marry an Irish native.

Such legislation marked an ominous note for the survival of Irish, and more serious threats to the language were to come. Introduced in 1537 by Mary Tudor, the plantation policy saw the suppression of Irish language and culture as central to colonial stability, and the large-scale introduction of non-Irish speakers to the country heralded a crisis of survival. After the Battle of Kinsale in 1601, the Irish-speaking aristocracy were driven out of the country, and with them went the backbone of Irish language and culture, the Brehon system of law, the bardic schools, and support for Irish poets and scholars.

The Cromwellian conquests of the mid-17th century drove the majority of non-English speakers out of the south and east, and although pockets of Irish speakers remained, the language became confined to the relatively harsh territories of Connaught. In the rest of the country, the notion that English offered an escape from poverty and oppression became widespread, and Irish was abandoned on a large scale.

Interestingly, the English language adopted around this time featured many of the Elizabethan traits that gradually disappeared from Standard British English, but contributed to the development of the distinctive “Irish brogue.”

The decline came rapidly after the 17th century. At the time of the Flight of Earls, Irish was spoken almost exclusively outside of the Dublin area; by 1799 the total number of native speakers had dwindled to just under half the total population of approximately 4.75 million. More serious reductions in the number of Irish speakers were to follow.

The National School system, set up in 1831, educated hundreds of thousands of children through English only, and stigmatized Irish as the language of poverty. But the most profound damage came with the Famine, which killed over a million and caused the emigration of another million and a half, largely from poorer, Irish-speaking areas. English became the key to escape and survival, as emigrants realized that Irish was of little use in finding employment abroad. Taken immediately after the Famine, the census of 1851 puts the number of Irish speakers at just 20 percent of the population.

But the years prior to the beginning of the 20th century saw a nationalist reaction against the Anglicization of Irish culture, and the language experienced the first stirrings of a popular revival. In 1893, the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was formed to reintroduce Irish as the vernacular of the nation; by 1904 it had almost 600 branches across the country. The league set up schools of Irish and helped repopularize traditional dancing and music through local and national competitions. Irish literature underwent a reappraisal in Irish language journals, and the league was instrumental in having Irish endorsed as a requirement for matriculation to the National University.

The Irish language became central to the politics of post-Independence Ireland – in 1937, the Constitution recognized Irish as the first official language of the state – and successive governments have attempted to foster its survival and expansion. But despite social and economic initiatives like the Gaeltacht Commission and the appearance in 1967 of Radio na Gaeltachta (an all-Irish radio station), everyday use of Irish continued to decline. By the early 1980s, the number of native speakers had fallen to between 30- and 50,000 people, with many of these bilingual.

℘℘℘

The Future of Irish

The 1980s and early 1990s revived hopes that the decline could be reversed. Government grants boosted the number of gaelscoileanna (Irish language schools), and currently, around 60,000 children are educated solely in Irish.

Meanwhile, continued support for the language through subsidies for Irish-language publications, an Irish language national radio station as well as TG4, an award-winning public service TV station broadcasting through Irish, helped bring the language into living rooms on a daily basis.

In 2010, the government launched a 20-year “Strategy for the Irish Language” with specific objectives to increase the number of people with a knowledge of Irish to 2 million and raise the number of daily speakers to 250,000.

The strategy has more than half its timeframe yet to run but the latest national census of Ireland has set alarm bells ringing and raised questions over the future of Irish as a living language.

Figures published this April reveal that around 1.7 million claim to be able to speak Irish, but outside of the education system, where learning the language is mandatory, fewer than 74,000 do so daily – a far cry from the goal of the country’s official strategy for Irish.

Worse, the census shows a significant fall since 2011 in the number of Irish speakers in Ireland’s eight Gaeltacht areas, which are specifically denoted as primarily Irish-speaking. In Mayo, for example, the number of people speaking Irish on a daily basis in 2016 was 25 percent lower than just five years previously, while in the Kerry Gaeltachts, the number of daily speakers has fallen by 18 percent.

The decline is the first in more than 80 years, leading some to suggest the figures point to the potential extinction of Irish as a living language.

Much of the blame may lie with emigration during the post-Celtic Tiger economic crash, but questions must be asked regarding why a language that is a mandatory subject in all Irish primary and secondary schools is essentially discarded by students after their final exams.

Whatever the reasons for the decline in daily usage, the danger of a continued decline is clear.

According to Padraig MacFheargusa, language activist and editor of the Irish language monthly Feasta, the situation highlighted by the census figures is worrying, but there are some silver linings too.

“Leaving the major languages aside, there are about six thousand languages on the planet, and on average, they each have about 8,000 speakers. In that context, Irish is well off: it has a degree of state backing, and the people speaking it are not impoverished as they were in Famine times,” he says.

And despite the shrinking usage revealed in the latest census figures, Irish is thriving in some areas, he says – particularly in the U.S.

“I think there are about 50 universities which have courses in Irish language and culture in the U.S.A., and the interest there is growing,” he says.

MacFheargusa believes the Irish in Ireland are doing a “disservice” to the diaspora if they do not change their mindset towards the daily usage of Irish.

“The present situation is an ongoing cause for concern – but not hopeless. The Irish are not a poor nation, and they have a state which can ensure that services are provided through Irish so that the status of the language is maintained and people are encouraged and secured in their use of it,” he says.

“I think too that this most significant and distinctive product of Irish culture and civilization, the Irish language, will not be easily abandoned: people do not give up on their efforts to be fully human.

“We have to be hopeful.” ♦

℘℘℘

Look-alikes, Sound-alikes and Distant Relatives

Irish shares its origins with hundreds of others in the Indo-European family of languages. Effectively, Irish is a cousin to many of these languages and dialects – although a distant cousin in some cases.

For example, the Irish word for horse, capall, has a family resemblance with the Spanish caballo, French cheval, and Italian cavallo, while the names for some body parts also have cognates that reflect a shared origin – the Irish word for tongue, for example, is teanga, compared to the German zunge, French langue, and Swedish tunga.

Numbers also share certain family characteristics across a diversity of languages:

English: One, two, three, four five

Irish: aon, dó, tri, ceathair, cúig

Breton: unan, daou, tri, pevar, pemp

French: un, deux, trois, quatre, cinq

Italian: uno, due, tre, quattro, cinque

But the family connection between Irish and other languages runs further afield too – often in some surprising directions.

Sanskrit, for example – the ancient language in which the Hindu scriptures are written and from which modern Indian

languages derive – shares a range of characteristics with Old Irish that reflects their shared Indo-European origins.

The Sanskrit word for “freeman” is arya, which has an Old Irish cognate aire, meaning “noble,” while the Sanskrit word for “good,” naib, is a cognate of the Old Irish word noeib, from which the modern Irish word naomh, “saint,” derives.

The shared origins between Old Irish and Sanskrit are also

evident in minda (Sanskrit for physical defect) and menda (Old Irish for a person with a stammer), and perhaps most clearly in Raj (Sanskrit word for king) and the Old Irish cognate Rí.

Other comparisons include the Sanskrit badhira (deaf), which is bodar in Old Irish, while the Sanskrit pibati (drink) is reflected in the Old Irish ibid.

Irish and Hindu are frequently highlighted as cognate cultures, but such connections are more than merely historic or academic. The Industrial Development Authority, the government body charged with attracting foreign investment into Ireland, continues to highlight the shared language links with India as part of its campaign to attract Indian companies to the country.

Old Irish also has a kinship with a range of other languages, both in Europe and very much further afield.

For example, the link between the Irish word for mother, máthair, is easily detectable in modern European languages like French (mère), Spanish (madre) and Portuguese (mai), but also in Iranian (matar), Armenian (mayr) and Albanian (moter). ♦

_______________

Colin Lacey is the editor of County Kerry’s biggest-selling weekly news-paper, Kerry’s Eye, based in Tralee, in the southwest of Ireland. He was a frequent contributor to Irish America and the Irish Voice, as well as other U.S. publications in the 1990s, when he lived in New York.

NOTE: The terms Irish and Gaelic are often used interchangeably, but in terms of language, it’s more accurate to describe Irish as a form of Gaelic (along with Welsh, Manx, Scots Gaelic, etc.).

I really enjoyed reading this article. When I went to Ireland 5 years ago and heard some relatives in Dingle speaking Irish I was determined to do so as well. When I came back to NY I found that Molloy College on Long Island had classes so I started. It has not been easy but I am determined to become fluent for as long as it takes. For the Irish to lose Irish makes as much sense as the France to lose French or Italy Italian. Language is part of your culture and if you lose that you start to lose the rest of your identity.

Great synopsis, Colin. My mother was from Kilgalligan in northern Erris, Mayo and she had to learn English in School. I remember her story that her name was Caitche(Katchee) U Murachu and when she went to school and they were teaching her the Bearla they said her name was now Katie Murphy. And as far as the connection with Sanskrit there are many instances I’ve read of that indicates that, including the tale of the Irish soldier in the English army in India in the 19th c who was able to converse in Irish with some of the local peoples in central India because their language was very similar. Anyway, thanks for such a well written account. My Mom usta joke about the spelling changes in the Irish language by the Gaelic League in the early 20th c where apparently, they tried to eliminate any phonetical spellings that English speakers might find easier to learn. SDhe said it was easier for her to read the older spellings in the books she had. Her tongue in cheek, but practical response to that understandable political action was that it was harder to read for her until she figured out that: “..the longer the word, the shorter the sound.” lol