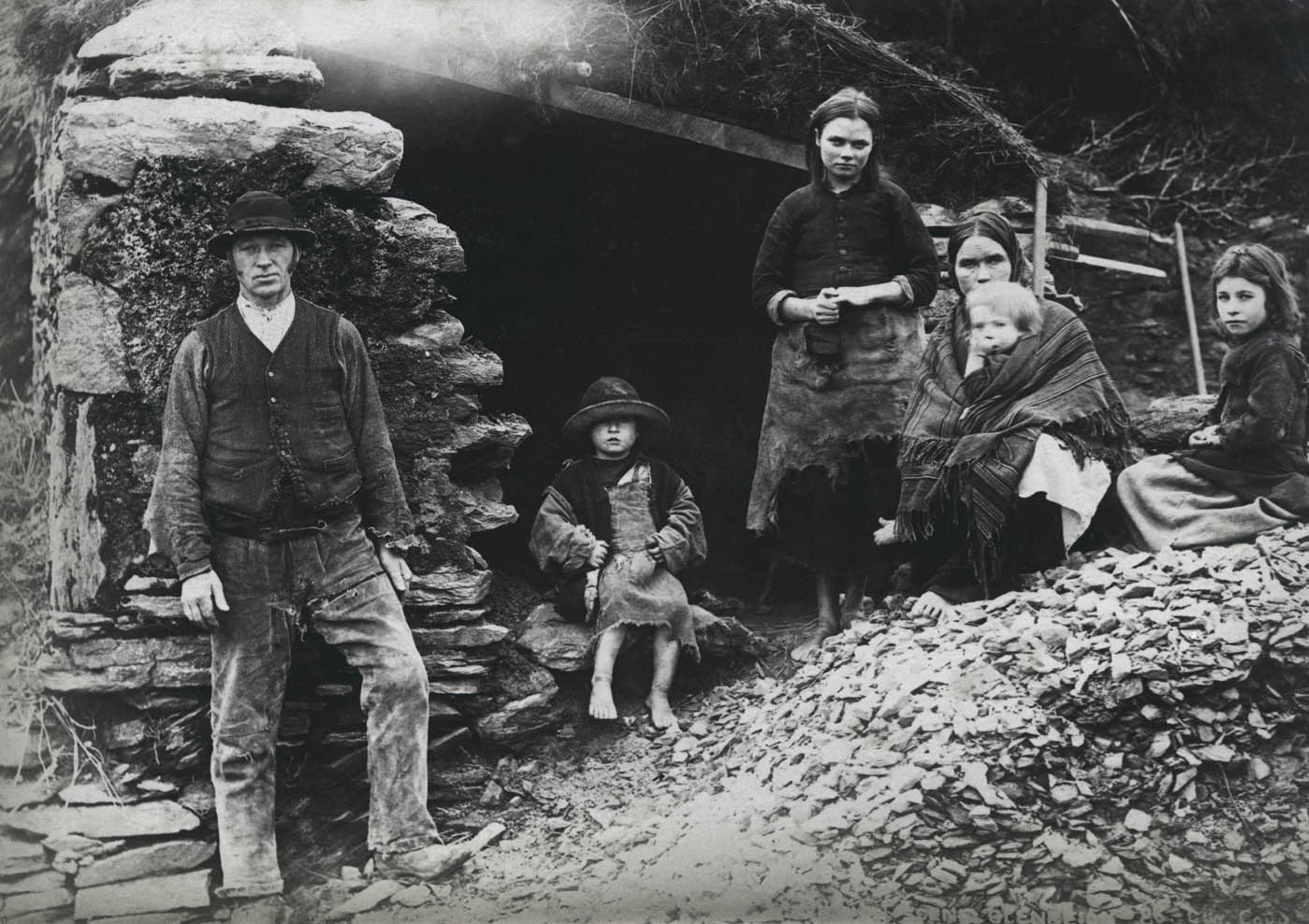

Sean Sexton’s photographic archive, considered the finest privately-held collection of Irish photographs in the world, provide a poignant photo-history of evictions in the final decades of the 19th century. These images created a wave of sympathy for Irish tenants and embarrassed the British government into making legislative changes.

In 1900, Queen Victoria visited Ireland for the fourth and final time. She was an octogenarian, almost blind, and wheelchair-ridden. She came not to say farewell to her Irish subjects, but to raise more soldiers for yet another imperial war – this time against the Boers in South Africa. Her visit was met with protests from militant nationalists, including the dazzling Maud Gonne, who was prompted to write a newspaper article, which was instantly banned by the Irish authorities. The title of the article was “The Famine Queen,” a name that has persisted. Gonne wrote:

“And in truth, for Victoria, in the decrepitude of her 81 years, to have decided after an absence of half-a-century to revisit the country she hates and whose inhabitants are the victims of the criminal policy of her reign, the survivors of 60 years of organized famine, the political necessity must have been terribly strong; for after all she is a woman, and however vile and selfish and pitiless her soul may be, she must sometimes tremble as death approaches when she thinks of the countless Irish mothers who, sheltering under the cloudy Irish sky, watching their starving little ones, have cursed her before they died.

“Every eviction during 63 years has been carried out in Victoria’s name.”

Should Queen Victoria be judged by the policies carried out by her government ministers during her long reign (1837-1901)? Is she culpable for the hunger and famines that occurred throughout the British Empire while she was monarch?

The most famous Victorian-era famine took place at the heart of the empire, in Ireland, in the 1840s – a famine that within only five years claimed over one million lives and forced an even greater number to leave the country of their birth. Death did not wait long to claim them, as the average survival rate of an emigrant who made it to North America was only six years. The question remains – how could such a lethal famine have occurred at the heart of the richest empire in the world?

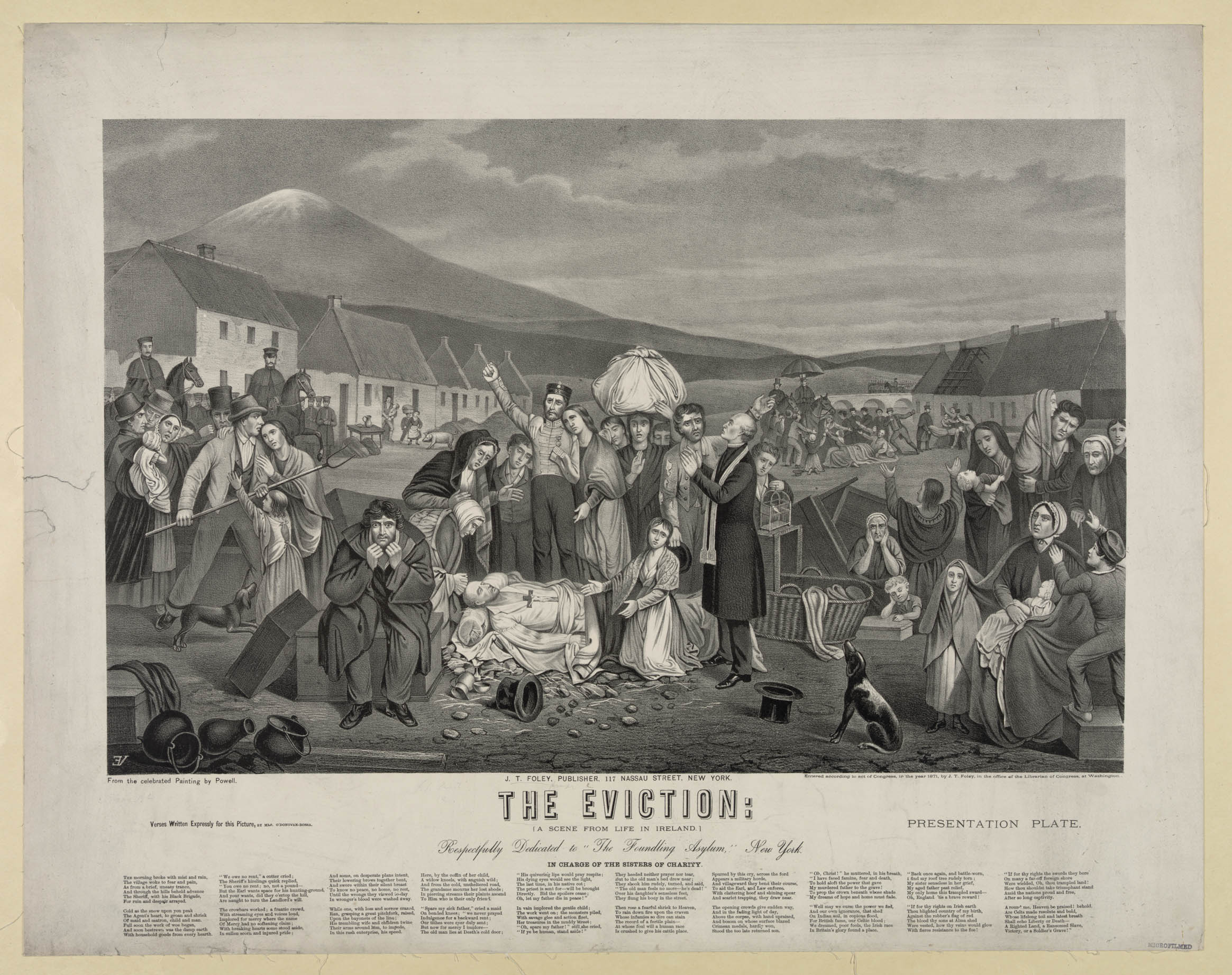

One of the cruelest aspects of the treatment of the Irish poor was the mass evictions that accompanied the mass hunger. Records were not officially maintained until 1848, so precise numbers are not known, but it is estimated that as many as 400,000 individuals were driven out of their dwellings in the late 1840s. As evictions were the result of human agency, they could have been prevented or regulated. The failure to do so meant that, as the Great Hunger unfolded, homelessness joined hunger as a major source of disease, dislocation, and death.

Nor was it simply nationalists who feared the consequences of such cruelty. At the end of 1848, Lord Clarendon, the Viceroy in Ireland, privately lamented that the British government’s failure to help the Irish poor meant that they had “coldly persisted in a policy of extermination.” In contrast, Charles Trevelyan, the dogmatic secretary of Her Majesty’s Treasury, defended both the mass evictions and mass emigration on the grounds that, “We must not complain of what we really want to obtain. If small farmers go, and then landlords are induced to sell portions of their estates to persons who will invest capital, we shall at last arrive at something like a satisfactory settlement of the country.” For Trevelyan, the human dimension – dislocation, dispersal and possible death – was not a factor.

Although not on the scale of the tragedy of the late 1840s, crop failures persisted in the late 19th century. In 1860-62, 1879-82, 1895, and 1898 there were localized famines in Ireland, each resulting in an increase in eviction, emigration, and mortality. Moreover, in the wake of the Great Hunger, the commercial agricultural sector moved from corn to pasture. In the post-Famine decades, therefore, sheep replaced people in many rural areas.

The years 1879 to 1882 are referred to by some historians as “the forgotten famine.” This subsistence crisis was mostly confined to the west of Ireland, particularly counties Mayo and Galway. While there was an increase in mortality, subsidized emigration, and private relief provided a safety valve for the poor, lessening the impact of the shortages. However, as in the earlier crisis, the agricultural distress was accompanied by widespread evictions. Unlike in the 1840s, some of the most dramatic of these evictions were captured on camera.

At the time of the Great Hunger, photography was in its infancy. By the 1880s, it was still a slow and expensive process, which was largely the preserve of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy. However, new developments in journalism and the print media meant that photographs were used increasingly in newspaper reports on both sides of the Atlantic.

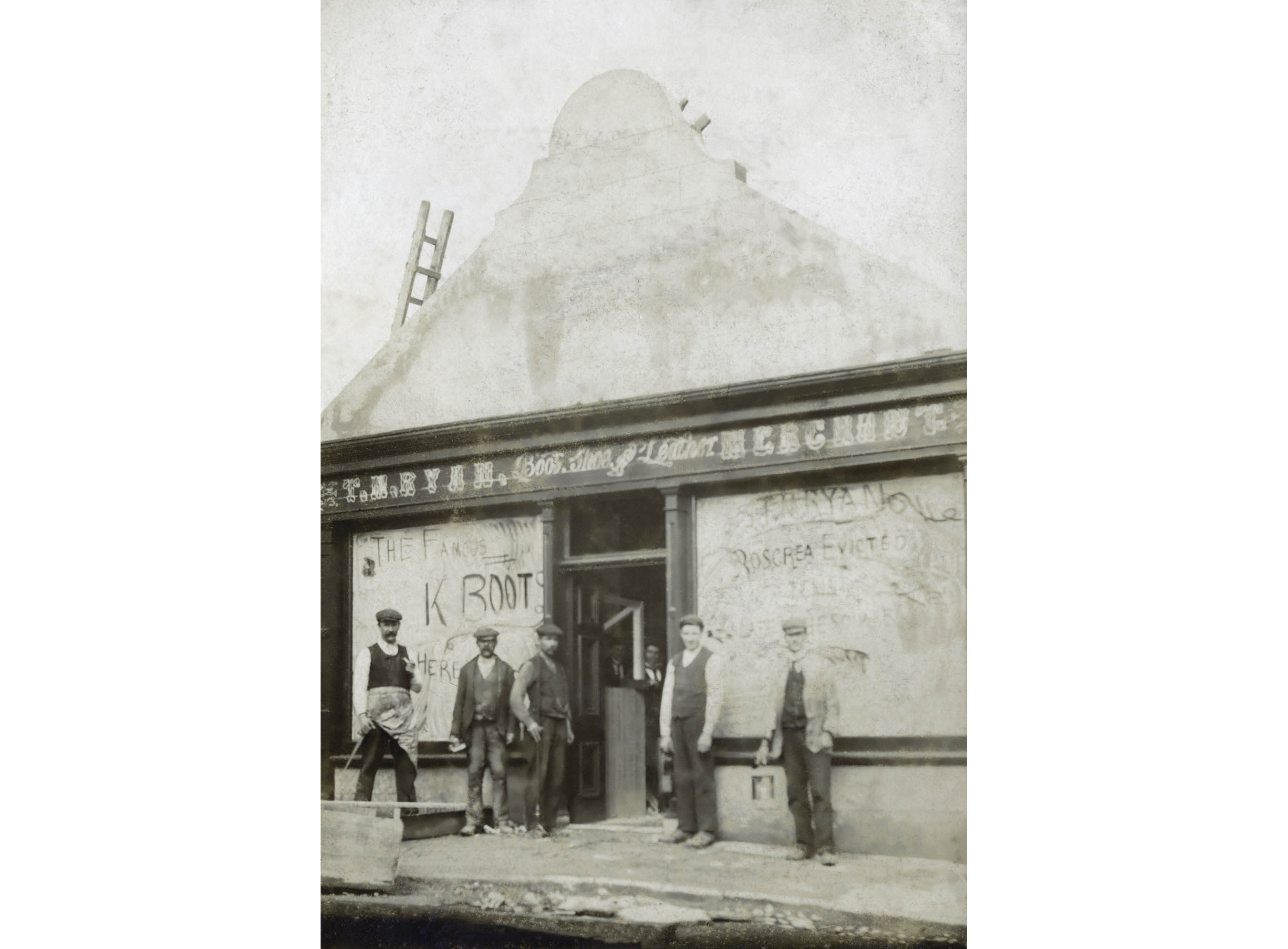

Sean Sexton’s photographic archive, considered the finest private collection of Irish photographs in the world, provide a poignant photo-history of evictions in the final decades of the 19th century. Some of these images are familiar, but they still have the power to shock. What is particularly striking is the juxtaposition between the use of armed police and eviction gangs, equipped with massive battering rams and observed by magistrates and other well-dressed local dignitaries, evicting poor families who were defending their homes with barricades made of shrubbery and cow dung, their only weapons boiling water or urine. Sexton’s photographs remind us of the quiet dignity of a people thus dispossessed, juxtaposed against the military might of those evicting them.

There were a number of differences between the evictions that took place in the 1840s and those in the 1880s. In the earlier decades, the process was completed using a crowbar; by the 1880s, the use of a battering ram was more prevalent. More importantly, while in the late 1840s, no organized resistance had been in place to defend those evicted from their homes; by the 1880s, many evicted tenants did not give up their homes quietly. A new wave of nationalists, ably supported by emigrants in North America and alarmed by the specter of another major famine in Ireland, mobilized under the leadership of the newly formed Land League. The type of resistance favored by the Land League was peaceful, summed up by the use of the appropriated word, “boycott.”

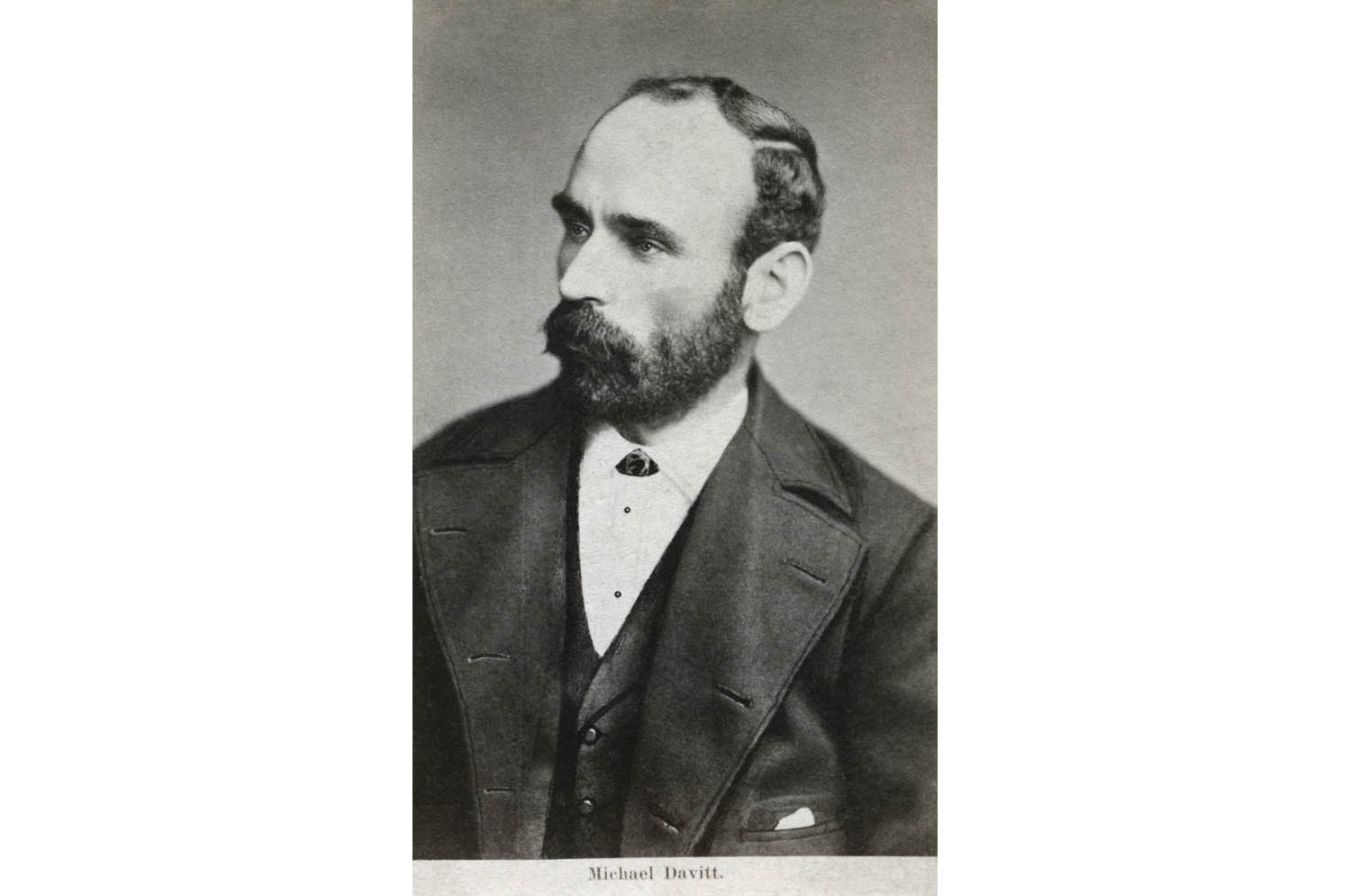

Ironically, the president of the Land Leagues was Charles Stewart Parnell, himself an Anglo-Irish landowner in County Wicklow. In contrast, Michael Davitt, the honorary secretary (and the real moving force), had first-hand knowledge of eviction and of the Great Hunger. In 1850, his family had been evicted from their small-holding in Straide, County Mayo. The Davitts were amongst the minority of poor emigrants who travelled no further than Britain. There, the young Davitt worked in a cotton mill in Lancashire, where his arm got trapped in machinery and had to be amputated. He was aged only 11. His experiences shaped his subsequent politics, summed up by his slogan, “The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland.” Davitt realized that in the struggle for tenant rights, photographs were a powerful tool in the propaganda war against both landlordism and British rule.

A further significant development was the prominent role played by women. While women had been part of earlier nationalist movements, they had largely been invisible. Fearing that the male leadership of the Land League was about to be imprisoned, Michael Davitt determined that a Ladies’ Land League should be created in North America. Fanny Parnell (Charles’s sister who resided in Bordentown, New Jersey) agreed to carry on the work of resistance and to provide support for evicted families. Within weeks, she had established almost 100 women’s leagues in North America. Her organization provided a model for the creation of an Irish Ladies’ Land League, managed by Anna Parnell, Charles’s other sister. The two women’s organizations were efficient and effective, but short-lived. Charles, who had never supported the idea of women’s involvement, abruptly dissolved them as part of a larger get-out-of jail package. Anna never spoke to him again; Fanny had prematurely died, aged 34.

Regardless of the early successes of the Land Leagues, large-scale evictions continued throughout the 1880s, with some, such as the 1887 Bodyke evictions in County Clare, attracting international press coverage and notoriety. Embarrassed, the British government asked that further evictions be limited while media interest continued. On this and other occasions, there is no doubt that the photographs, and other images, created a wave of sympathy for Irish tenants.

Reluctantly, the British government did pass piece-meal legislation to reform the system of land-holding in Ireland, notably in 1870, 1881, 1903, and 1909. Collectively, these laws changed the structure of land ownership in Ireland, which constituted a social revolution in the countryside. However, for hundreds of thousands of people who since the Great Hunger had been ruthlessly evicted from their homes and forced to shelter in hedges, or be humiliated in the workhouses, or seek a new life in a land across the seas, this intervention was too little, too late.

When Queen Victoria made her final visit to Ireland in 1900, Michael Davitt’s wife, Mary Yore, made a banner simply saying “E-Victoria.” For republican nationalists, Victoria had become a symbol of British misgovernment of Ireland, while evictions, emigration and famines were part of the price that the Irish people had paid for decades of misrule.

_______________

Professor Christine Kinealy is director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University. Her publications include the edited collection Woman and the Great Hunger in Ireland (Quinnipiac and Cork University Presses, 2016) and An Droch Shaol (Coiscéim, 2016).

This article was published in the April / May 2017 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply