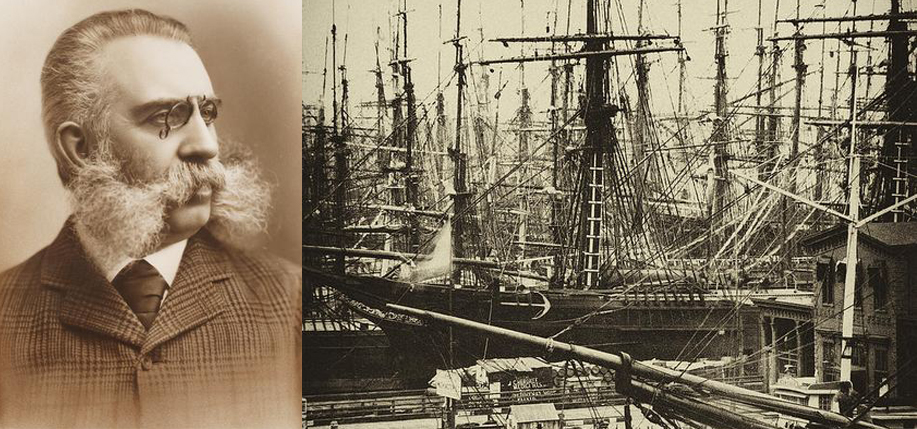

John Wolfe Ambrose emigrated from County Limerick as a boy and went on to leave an indelible mark on New York City. He cleaned the streets and turned New York Harbor into a world port.

Like a true Renaissance man, John Ambrose had many interests and talents. His son-in-law, George F. Shrady, Jr., said his “giant intellect, coupled with his remarkable executive ability and constructive genius, conceived plans for public improvements so vast and comprehensive that he occupied a unique position among men in that he was far ahead of his time. He was one of our most public spirited citizens, to whom New York owes an eternal debt of gratitude.” Shrady further described Ambrose as “a man of commanding presence,” who possessed “a keen sense of humor, and was by nature genial and kindly.”

Ambrose did indeed accomplish a great deal for the city in his lifetime. He built the Second Avenue elevated train, installed 90 miles of gas mains, designed the city’s street cleaning program, developed the South Brooklyn waterfront for shipping, operated a ferry company between there and lower Manhattan, and created an amusement park that saw the likes of Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley. But his tireless efforts to get a recalcitrant Congress to appropriate funds to build the deep shipping channel that kept New York Harbor a world port by the beginning of the 20th century is his most lasting gift.

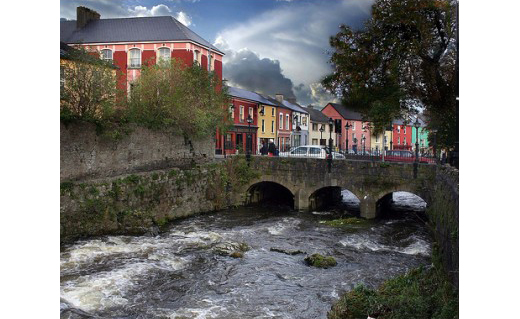

An Immigrant from Limerick John Wolfe Ambrose was born January 10, 1838 at New Castle, County Limerick. He was 12 or 14 when he came to New York with his parents and possibly other family members, including two sisters, but little is known about his early life or parents. A cousin, Daniel Ambrose, came to New York in 1865 and became a prominent physician in Brooklyn Heights. Another physician cousin, J.K. Ambrose became the Staten Island coroner. According to Arthur Ambrose, a descendant of Daniel speaking in 2003, the earliest Ambrose ancestors were farmers, but there were many doctors and ministers in the family in Ireland.

Ambrose himself had planned to become a Presbyterian minister and worked to attend the Princeton Theological School (now Princeton University), founded by primarily Scotch Irish Presbyterians. He left after a year to attend the University of the City of New York (now New York University), where he found a mentor and lifetime friend in Dr. Howard Crosby, a Greek scholar with whom Ambrose enjoyed reading the classics – in Greek – for many years. In addition, his curriculum included algebra, geometry, trigonometry, surveying, calculus, and analytical geometry, which helped him establish a career in civil engineering.

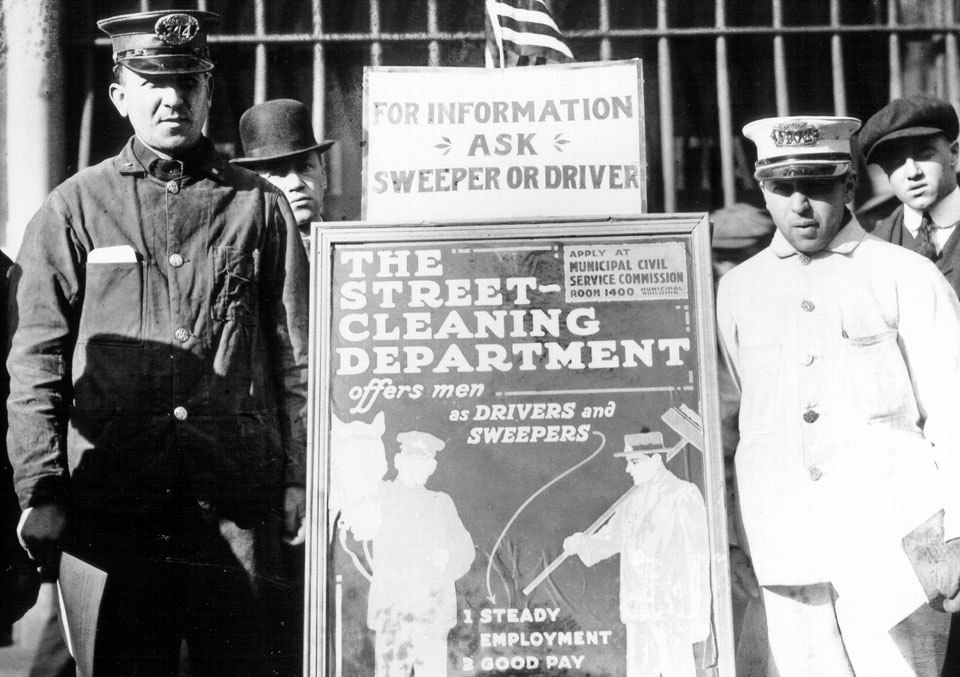

In 1862, after his studies, Ambrose, who was focused on public service, took a newspaper job with the official organ of the Citizens Association, one of the first civic organizations devoted to municipal reform and the forerunner of the city’s Board of Health. Here he worked with Dr. Stephen Smith, who would become a lifelong friend and personal physician. Smith recognized that outbreaks of typhus and cholera were related to the dreadful environmental conditions in the city, where the average life span was 41 years. City streets at that time were rank with horse manure, dead animals, and all manner of “rubbish” left for scavengers. Waste collection and street cleaning were handled by the Metropolitan Board of Police until the Department of Street Cleaning was created in 1881. A street cleaning program designed by Ambrose and using white-uniformed workers with carts and brooms was put into use.

After his studies, Ambrose married Katharine “Kate” Weeden Jacobs, daughter of George Washington Jacobs, from a prominent family in Hingham, Massachusetts, and Nancy Weeden Jacobs, whose ancestors were settlers in colonial Manhattan. They eventually lived in a townhouse at 575 Lexington Avenue, at 51st Street. In the tradition of Kate’s family, and a popular custom of the time, their sons were named for famous Americans: John Fremont and Thomas Jefferson Ambrose. They also had three daughters, Katharine, Ida Virginia, and Mary.

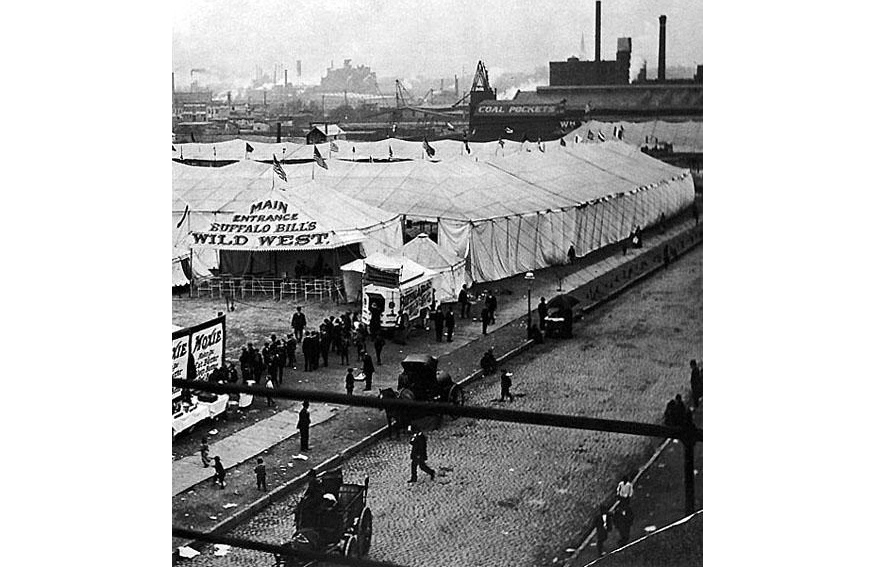

A Vision for the Harbor As his family grew, Ambrose established a contracting business, J.W. Ambrose and Company, to develop more ways to improve the city, especially its harbor. While the Brooklyn waterfront along the East River opposite Manhattan had been developed, the shore line nearer to the Narrows, from Red Hook to Bay Ridge (the broad part of the lower harbor leading to the Atlantic Ocean) was largely undeveloped. Ambrose saw opportunity here for piers to accommodate increased shipping with easy access from the Narrows into the ocean. He founded the New York and South Brooklyn Ferry and Steam Transportation Company in 1886 with plans to build and lease fast double-decked iron boats. To inspire people to travel to South Brooklyn, Ambrose Park was created near the ferry terminal, at 37th Street and Third Avenue, which was leased out for entertainment, such as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Previously, no space in New York was big enough to handle the crowds as large as 16,000 persons these shows attracted.

As steam was replacing sail, ships were getting larger and more numerous, Ambrose saw the need for a deep water channel from the ocean into the harbor to accommodate steamships and protect the city’s progress as a great port. This lack was already drawing maritime commerce to other ports.

A Family Loss

Shortly after their 33rd wedding anniversary, Ambrose’s wife Kate died at home, surrounded by her family. She was 55 and had suffered from heart disease for several years and was cared for by the family’s long-time friend, Dr. Stephen Smith. However, on the Fourth of July, 1893, Kate succumbed to a blockage of the heart valve and edema of the lungs. After a private funeral at home, she was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, where the rest of her family would eventually join her.

By this time, the Ambrose children were establishing their careers in public service and the arts. Thomas Fremont Ambrose, widely known in musical circles, would be a director with the Oratorio Society, organized in 1873 by Leopold Damrosch and still in existence today. His sister Mary also sang with the society, as well as St. Paul’s Chapel Choir and the St. Cecilia Singing Society at Trinity Church, where she was active in social causes. Only two of the five children – Katharine and John – would marry, and both married into the family of Dr. George Shrady, the well-loved physician who cared for Ulysses Grant during his final illness in 1885. Katharine, who married George Shrady, Jr. in 1887, founded and was president of the Federation of Associations for Cripples, the forerunner to organizations helping people with disabilities. John Fremont, who married Minnie E.M. Shrady in 1888, founded the East Side Improvement Association, responsible for the development of Park Avenue.

A Final Victory

For the next five years, Ambrose continued his harbors efforts, despite the reluctance of Congress to give money to New York. The Rivers and Harbors Committee in the House of Representatives complained that New York already got $4.50 of every $5 dollars for river and harbor improvement. Ambrose set out to prove them wrong. He completed a 50-page document in 1898 called the “Congressional Appropriations Acts and the New York Harbor” showing that 56 percent of total commerce of the country passed through the port of New York and 69 percent of total revenues were furnished by New York, yet only one dollar out of every hundred dollars expended for river and harbor improvement in the five years ending in 1896 had been allotted to New York.

Ambrose organized a delegation of prominent and representative citizens from the Chamber of Commerce, the produce and maritime exchanges, the Board of Marine Underwriters, and the Merchants Association. On December 22, 1898, they appeared before the River and Harbor Committee advocating for a channel 2,000 feet wide and 40 feet deep. Ambrose made the principle address. It fell on deaf ears. The committee absolutely denied his plea, but not for a minute did Ambrose consider relinquishing a project so dear to his heart. He went alone to the Senate Committee on Commerce and met with its chairman William P. Frye of Maine, a leading force in the U.S. Senate for 30 years. “And by his masterly presentation of the subject, secured the appropriation that gave New York a suitable approach to its magnificent harbor,” Shrady later wrote.

A Celebration at the Waldorf-Astoria

The shipping and commercial interests of New York organized a public banquet to honor their colleague at the elegant new (original) Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Fifth Avenue and 33rd and 34th streets. Ostensibly to honor Senator Frye, the gala was obviously for Ambrose. Senator Frye accepted the honor of the dinner, but said that it belonged to “the persistency and the intelligent advocacy of one of your fellow citizens, Mr. John W. Ambrose, supplemented by the influence of our senators.”

Introducing Ambrose, Theodore Roosevelt, New York’s newly elected governor, called him “a man whose crowning achievement was that he had procured for the port of New York an entrance channel 2,000 feet wide and 40 feet deep from the Narrows to the ocean!” Everyone cheered loudly when Ambrose rose to speak, but with characteristic modesty, he played down his own role, explaining how Senator Frye had finally taken hold of the legislature and pushed it through. Newspapers all over the world reported on this event.

A Great Loss to the City

Ambrose did not live to see his dream a reality when, in 1907, the Lusitania would become the first ship to enter the Narrows through the new channel. On May 15, three weeks after the banquet, Ambrose died of typhoid malaria. He was 61. According to the New York Times, “he was sick about 10 days, his illness having been caused, it is believed, by the escape of poisonous gases from a neglected ruin near his office on Pier 2 East River.” Ironically, the city’s sanitation was not yet up to the standards he had helped create. “In the death of John W. Ambrose this city has lost one of its most public-spirited and useful citizens,” wrote the New York Daily Tribune.

John Ambrose’s funeral was held at the Methodist Episcopal Church on Madison Avenue at 60th Street. He was buried in the Green-Wood Cemetery next to his wife Kate.

In its 1901-2 session, Congress passed a bill to name the channel for Ambrose. In 1908, a lightship was christened Ambrose and stationed at the entrance to the channel that bears his name. This floating lighthouse guided ships safely from the Atlantic Ocean into the broad mouth of lower New York Bay. Sixty years later, in 1968, after a permanent light station resembling an oil rig had been erected, the U.S. Coast Guard gave the lightship to the South Street Seaport Museum, where it has been restored and is open to visitors. It is a National Historic Landmark.

Shortly after Ambrose died, his colleagues presented to his family a life size bronze bust of Ambrose created by sculptor Andrew O’Connor. Katharine, who would outlive her siblings and her husband, decided to present the bronze to the city in 1936. Thus, 37 years after the death of John Ambrose, the Department of Parks unveiled the bronze bust set on a plain granite plinth with a low relief carving of the waves and map of the harbor placed on the wall of Castle Clinton at the Battery, which by this time had become home to the New York Aquarium. However, the monument was stolen in 1990 and never found. Now, 27 years after the theft, the New York City Department of Parks will install a replica of the bronze bust at the east side of the Battery, near State Street. ♦

_______________

This article is adapted from Marian Betancourt’s latest book, Heroes of New York Harbor: Tales from the City’s Port (Globe Pequot, 2016). Many of the heroes are Irish Americans.

Read about the rededication of the John Wolfe Ambrose statue here

Glad to have learned about Mr. John Wolfe Ambrose.

Could you please tell us, by now, where the restored sculpture bust is? It was stolen in January 1990. There have been various news articles reporting the restoration project since March 2014. We can’t wait to see this monument. It would be great for people to visit on St Patrick’s Day this Friday, March 17, 2017.

Thank you!

The NY Parks Department has restored the bust and it will be placed in Battery Park later this year. Marian Betancourt

I think this article would have benefited from the 1000-word limit imposed on other contributors. For instance, at the beginning, you tell us, Ms. B, three separate times that this saintly gentleman was born in Limerick.

“Renaissance man” is an outworn cliche. Try “polymath” next time, send people to their dictionaries, online or otherwise.

I think the information is interesting, the story is, but reduced to 1000 words the presentation might have been more exciting.

Tagus dut,

Peadar

I am a first cousin three times removed to JWA. He also was a first cousin of another Westminster MP, Dr Robert Ambrose.

I am also related to John Wolfe Ambrose. He was my 3rd great-granduncle. I think it was a terrific article (ignore the negative comments above). I have been researching the Ambrose Clan for decades and have found exactly when John Wolfe Ambrose came to the US. He arrived with his mother and siblings on Aug. 22, 1851, on the City of New York. His father, John, had come a few months earlier, in May 1851. So, he was 13 years old. His oldest brother, James, came to America later (perhaps 1853) and went on to become a distinguished police constable in Richmond, Staten Island. But John arrived with his mother Bridget (“Delia”), sisters Johanna, Mary, and baby Bridget (“Delia”), and brothers Thomas (my 3rd great-grandfather), Patrick, and Michael.

As for the bust being restored, I have been communicating with the City Parks Dept. for several years now and they are VERY close. In fact, we are hoping to organize a re-dedication ceremony, for the public to attend–not to mention, as many Ambroses as possible. Please contact me if you are interested in attending this potential event. Also, I would like for you (the author) to contact me directly, so that we can explore this topic further. Thanks so much for providing so many wonderful details about such a remarkable man.

A few corrections are in order. You do not have the correct date for when the first ship entered the newly-dredged Ambrose Channel.The Lusitania arrived in September1907. You also incorrectly stated his son’s name was Thomas Fremont. It was Thomas Jefferson. (His other son was John Fremont.) And you also listed his burial date for his death date. He died on May 15, 1899.