Recently published books of Irish and Irish American interest.

℘℘℘

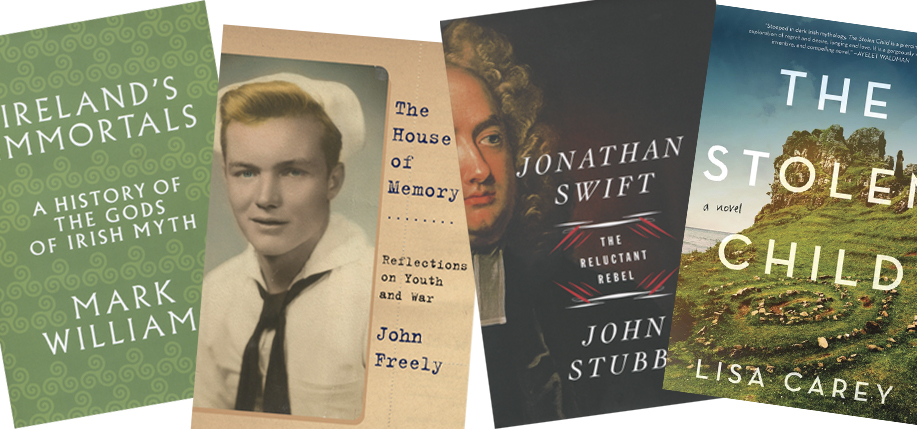

Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth

By Mark Williams

In the midst of the Celtic Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, W.B. Yeats implored his Irish literary compatriots to “go where Homer went.” It was an audacious urging, to formalize a relationship between Ireland’s mythological pantheon and the classical gods of ancient continental Europe, to write into existence as rich a cultural and literary heritage as the Greco-Roman deities held in the popular canonic imagination. The task, taken on by Yeats, as well as writers like George Russell, Austin Clarke, and Lady Gregory, was somewhat complicated by the fact that until the century prior, the mere intellectual concept of a native pantheon of Irish gods was unavailable to Irish writers, having largely been abandoned by the late middle ages. Moreover, writes Mark Williams in his excellent new book on the subject of Irish gods, they are notorious shape shifters.

“At times they resemble the Olympian divinities as a family of immortals ruled by a father-god, but at others we find them branching into a teeming race of supernatural nobility, an augmented humanity freed from ageing and artistic limit,” Williams, a lecturer in medieval Irish, Welsh, and English literature at Lincoln College, University of Oxford, writes in the preface. “They are simultaneously a pantheon and a people.”

Beginning on pre-literary archeology, and then drawing on 1,500 years of writing, in Irish and English, Williams attempts to definitively chart the written and popular history of the Túatha Dé Danann, the Peoples of the goddess Danu. Some names may be familiar to those familiar with the legends – Lug, an adolescent warrior linked to skill, craft, and the arts; Morrígan, a war goddess; Manannán, the sea god; Oengus Óg, god of love; or Brigit, goddess of fire and healing – but this is less a book about telling the myths than getting to the root of who these deities were for the medieval Irish, and how they evolved in the Irish cultural tradition, right up to contemporary children’s literature and pop music.

Ireland’s Immortals, published by Princeton University Press, is unmistakably a scholarly work undertaken by a professional literary critic – it will make you work for your learning. Yet the writing, which is at once compelling, discursive, and personable, makes it a book that can be enjoyed by people of all interest levels in Ireland’s mythology.

– Adam Farley

(Princeton / 608 pp. / $39.50)

The House of Memory: Reflections on Youth and War

By John Freely

It’s still possible to be related, in living memory, to Irish people who never owned shoes until they came to America. So it is with the elegant memoirist John Freely, born in 1926, whose mother, Peg, and father, John, spent the early part of the 20th century growing up in a nation as lost to time now as the mythical Tír Na nÓg, the Land of the Young.

In The House of Memory, he recalls how as a girl his mother was walking home from school barefoot next to her more prosperous shoe clad friend when the local priest, Father Mulcahey, paused next to them in his passing horse and carriage.

Peg recalls how he offered a lift to her well-shod classmate but not to Peg, who had to walk home alone though three miles of freezing rain, filled with an anger that welled up every time she thought of him for the rest of her life. It contributed, no doubt, to her ardent and lifelong atheism.

Freely’s memoir is filled with these kinds of vivid incidents and characters, and now, at the age of 90, he’s become a living embodiment of the American century, having made the kind of journeys that in many ways exemplify the Irish immigrant journeys of the last century.

Traveling to Ireland to winter out the worst years of the Depression as a child, the experience of trans-Atlantic travel set his young imagination ablaze and later in life filled him with the unquenchable desire to see the world.

In 1944, at 17, he joined the U.S. Navy and was sent into the Pacific theater of World War II, helping to bring supplies and ammunition to the U.S. Allied Forces before he had even turned 20.

After the war he married, graduated from Iona College, earned a Ph.D. in nuclear physics from New York University and did post-doctoral work at All Soul’s College in Oxford. Then he taught for 50 happy years at Bosphorus University in Istanbul, where a building is now named after him.

In this marvelous book, with its echoes of Angela’s Ashes and Brooklyn, Freely paint an unforgettable portrait of a richly-lived Irish American life. What’s remarkable is how youthful his outlook has remained, and his humor and gratitude now seem to belong to a vanished gentility, and his memoir reminds us that the immigrant’s tale is also the quintessential American one.

– Cahir O’Doherty

(Knopf / 272 pp. / $26.95)

Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel

By John Stubbs

It is no small undertaking to chronicle the life and times of someone whose notoriety arose from a legacy of artifice. To understand the specific distinctions between fact and fiction, meat and mask, one must read between the lines of history. As such, English biographer John Stubbs’s Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel is as much a study of the 17th century satirist, poet and priest’s psychological profile as it is of the wider political and literary impact he had at the time.

Stubbs notes early in the biography that Swift, the mind behind the classic traveler’s tale satire Gulliver’s Travels and Juvenalian essay “A Modest Proposal” (which mocked British attitudes towards Irish food shortages and quality of life by detailing a plan to turn children into an edible resource), was, “to his regret, an Irishman.” Despite the presence of something akin to sympathy for the people of Ireland evinced by his work, Swift, born in Dublin in 1667, would spend his career insisting his “rightful home” to be England, a sentiment that, due to the British presence in Ireland at the time, was commonly accepted by his peers.

Stubbs provides thoughtful evidence that this duality was a recurring theme in Swift’s highly-eventful 77 years – Swift was a stickler for cleanliness, yet strove to address the decay inherent to human nature through poetry; he spent years as a Whig pamphleteer, seeking the supremacy of parliament in Britain, but later as a conservative Tory, protecting the stability of the Crown’s interests. In discussing such a double-sided existence, Stubbs is never partisan, refusing to ever cast aside one part of a story in favor of a reductionist outlook or cast moral aspersions on the man who did so for a living.

“It is difficult merely imagining Swift, the Doctor and Dean, the terror of ministers and magnates, as a baby,” Stubbs writes. “Picturing it means endowing him with a vulnerability he cancelled altogether from his adult personality. But then, what should we expect?”

In The Reluctant Rebel, questions such as this are in no short supply, begging no answer, but instead proposing (at varying levels of modesty) a long, contemplative look at the hand that held the pen.

– Olivia O’Mahony

(W.W. Norton & Co. / 752 pp. / $39.95)

The Stolen Child

By Lisa Carey

The fairy folk of Irish myth refuse to coalesce with those of Grimm brothers fame. Fairies, in Irish tradition, are not sweet, earthly sprites, but rather the “Good People,” called as much only by their insistence, for to offend them would be a grievous mistake. In Lisa Carey’s The Stolen Child, this depiction holds true. All that the fairies give, they can also take away.

In 1959, the inhabitants of fictional St. Brigid’s Island stand on the cusp of mass evacuation to a suburb on the Irish mainland when an Irish American arrives on their shore. The tenacious ex-midwife, herself named Brigid, comes seeking a miraculous well that she hopes will grant her a child of her own. Instead she is met with stories of the Good People, rumored to work their mischief on the islanders when guards are low, “stories of women and children who fell under the world and refused to return, leaving a fairy changeling in their place.” She meets the caustic Emer, a local pariah, and her beloved six-year-old child Niall, for whom these are not just superstitions, but guidelines to avoid an otherworldly fate which looms ever-closer: Emer believes fairy magic will spirit Niall away on his seventh birthday, just as they tried to take her as a girl, instead leaving her tainted with a strange power that turns others away. Brigid and Emer, it turns out, have much strangeness in common, and, as their involvement moves from a platonic belligerence to furtive romance, it becomes clear that the Good Folk are not the only population of St. Brigid’s Island they have reason to fear.

The Stolen Child is a book of the magical realism genre in the vein of others before it, such as Joanne Harris’s Chocolat, Alice Hoffman’s Practical Magic, and Téa Obrecht’s The Tiger’s Wife. Carey’s luminous prose rearranges the lines between historical reality and old wive’s tale, and in doing so makes this story of motherhood, love, and loss inviolable to both.

– Olivia O’Mahony

(Harper Perennial / 400 pp. / $15.99)

Leave a Reply