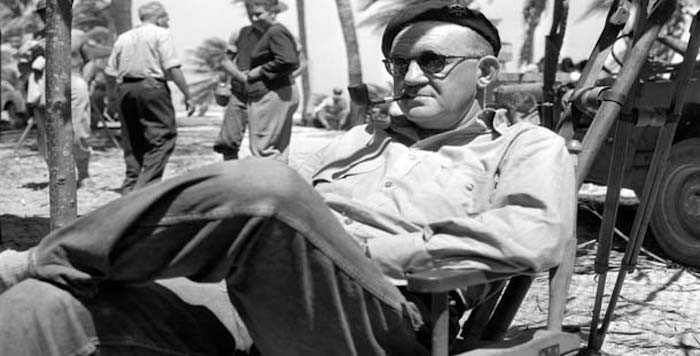

Film director Martin Scorsese was honored with the John Ford Award at the annual Irish Film and Television Awards presentation in Dublin on February 25, 2017. Scorsese was a huge fan of Ford as he explains in the following excerpt from a lecture given to the American Irish Historical Society.

John Ford was a true film pioneer. He began directing in his mid-teens. His first picture, Straight Shooting was released in 1917. He made one picture a week – a reel a week. That’s a one-reeler or a Western every week.

It wasn’t simply a matter of just going out and shooting a Western. For instance, you have to think, if horses are galloping out of the frame, left, where do they come in when you cut? Do they come in the same side? It will look as if they are going against each other. And the only way they worked this out was through trial and error, trial and error. These methods were constantly being created there on the set at that time. These are like subliminal images delivered to a mass audience that’s like one synthesized mind.

Ford is a director who means a great deal to me personally. I studied his films quite a bit. And also I watched them without studying them. I saw them on television, and I didn’t know who did them, but I knew they were good. I knew there was some sort of poetry going on there. I didn’t know what kind. But the images were so beautiful and the emotions were so strong. And over the years, I find that watching these pictures I learn more and more from them. The pictures are the same; I’m the one who is doing the changing. I have no idea how that happens, but I learn more when I see The Searchers, I learn more when I see The Long Grey Line, which at first I loved, and then, when I was a film student, I thought too sentimental. I saw it recently this year and it’s not sentimental, it’s sentiment. It’s a true sentiment. His films grow with each passing year.

As an Italian American, my family and I and my friends strongly related to the tribal nature of the cultures, and of the family in the Ford films as the unit, the foundation of identity and existence. The Irish and Italians, through the movies, were able to understand our common experience as immigrants and as the children of immigrants.

So there was a great deal of fellow feeling among Italian Americans when we saw these pictures from Ford. He was quite deservedly one of the most respected American directors of that Golden Age of Hollywood, the supposed Golden Age, the studio system. He was treated as a poet during a time when most directors weren’t getting that kind of respect. And one of the things that made his work so distinctive was that he filmed only what he had to film – nothing more, nothing less.

Now you have to understand that is not the way most pictures are made. Most directors don’t know exactly what they are going to shoot. They go ahead and they shoot what’s called coverage. They take a shot of you, a shot of you, a shot of you, up to me talking. Then, when they run into trouble with me, they go to you watching, to you watching, to my daughter watching. Then they cut back to me and changed all my lines. This is the way you build a scene.

But Ford didn’t do that. He knew exactly what he wanted. The late director Robert Parrish was an editor for Ford, and he died in 1995. He worked as an editor on The Grapes of Wrath, and he told a story about John Ford walking into his editing room smoking a cigar. This already is a problem. It’s already a problem because in 1939 you’re still using nitrate, and nitrate is flammable. A nitrate fire is very bad. You saw in Cinema Paradiso where the nitrate film burns. Also, Nanook of the North, the first documentary, directed by Robert Flaherty – there’s another Irishman – the father of documentary. Apparently, he was smoking in the editing room and he blew up all the film. He had to go back and recreate everything. At any rate, that’s how the story goes.

So obviously Mr. Parrish was quite nervous. Ford was standing there with a cigar. On the lot in those days, the editing rooms were really hot and claustrophobic. And the film is nitrate. Anything could happen. Now, when you cut a movie, each piece of film is identified with what they call a slate.

So Parrish told Ford, “I’m having a hard time cutting a scene on The Grapes of Wrath.”

And Ford said, “Why? All you have to do is go to the end of tile shot, cut off the slate, take the beginning of the next shot, cut off the slate, and put the two together:”

One of the reasons for doing this kind of thing with the studio, especially working in the studios where the producer was the king, was practicality. There was no way for studio heads to play around with Ford’s pictures because they could be assembled in only one way. They couldn’t be assembled in any other way. Actually, Ford didn’t take kindly to studio interference of any kind. He was shooting a Shirley Temple film he made with Victor McLaglen about the Black Watch called Wee Willie Winkie, at Fox again. Someone from the studio carne up and told him, “Look you’re five days behind.” So Ford ripped out twenty pages of the script and said, “OK, now we’re back on schedule,” meaning “Keep Away!” I’m sure that story’s been told many times.

One other beautiful story. I don’t know which film it was, but there is a story of John Ford watching John Wayne move in the distance. A stagecoach or a horse goes by and dust covers him, and this figure just stands there and Ford says, ‘Beautiful, this is beautiful. I’d love to take a close-up but some son-of-a-bitch would want to use it.” That was the end of that.

This annoyance with tampering relates back to what I was saying about these early directors learning how to tell stories with moving pictures. They learned through trial and error, and they knew exactly how to communicate the story. So they didn’t want anybody who just came on the set or on the lot telling them what to do. They were there at the beginning.

Ford was much more than just an iconoclast, although he certainly was that. He was something of a political conservative, I think. I can’t quite tell. For instance, he stood up to Cecil B. De Mille when De Mille tried to have Joe Mankiewicz removed as president of the Directors Guild of America because of his alleged leftist leanings. And De Mille, a director that I do like also – not that I think he’s as accomplished an artist as Ford – was red-baiting at that time. I read this in Kazan’s book. He began reading off the names of the leftist directors with a Jewish accent, Wyler, Zinneman, Mankiewicz. And I know Delmer Daves got up and spoke very emotionally. Wyler, too, got angry and wanted to hit somebody. William Wellman got very annoyed. And finally, at the climax of the meeting, which took seven hours – this was during the blacklisting period or right at the beginning of it – Ford stood up to challenge DeMille by announcing, “My name’s John Ford. I make Westerns.” And he made a speech and actually turned the tide with his natural sense of authority. He was there from before the beginning. What are you going to do? He made that speech from a sense of authority and his innate decency.

The way I look at Ford is as a poet. To me, he is a poet of elegy. Even when he was boisterous and trying to be funny, even when he does innumerable scenes with Victor McLaglen drunk and getting into all sorts of hijinks in the cavalry trilogy Westerns, there is always a feeling of elegy, of a past moment that’s been captured. The sense of aching beauty that you find in “The Dead,” the short story, of the past, haunting the present. This is John Ford.

In his film The Last Hurrah, which is about Irish politicians in Boston during the 1930s, there is this extraordinary sense of farewell, of the passing of an era. And done very simply: no fancy camera tricks, just the passing of time, done with beautiful reserve. It has to do with the way people carry themselves in the frame. The way they moved in the frame, Spencer Tracy and all the character actors, John Carradine, all these people. Even Jeffrey Hunter, who played Tracy’s nephew; Jimmy Galisa; all these great character actors. The movement is ritualized and the actors are respectful of one another in a way that’s subtle but very striking at the same time.

Ford also had an extraordinary eye for composition. Spielberg actually got to meet him. He went to a building in Hollywood one time – he had just come out of film school – and he saw, in the office across the way, John Ford working on a film. He was in there chewing his handkerchief, and Spielberg said, “Do you mind if I come in?” He walked in and said, “I’m a great fan of yours, I’m an admirer and I want to make movies.”

“You want to make movies, huh?” Ford said. “Study Remington.” Frederic Remington. And he said, also, “Watch where you put the horizon line. Don’t put it in the middle – always on the top or at the bottom. Never in the middle.”

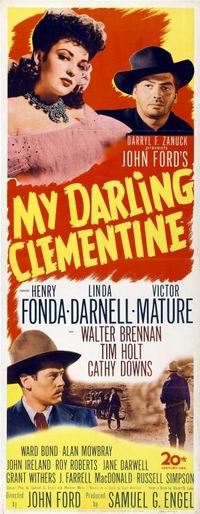

But study the composition. This is a key thing in Ford’s work. As can be seen in a bar scene from My Darling Clementine, his storytelling was very clear, very visual, and his images had a real weight, a density. My Darling Clementine and The Searchers, by the way, are the two great Westerns, arguably. Everybody knows Stagecoach, but My Darling Clementine has a special quality. I just saw it again a few weeks ago. But in this scene, you can see all of these aspects of Ford as well as his beautiful sense of chivalry. Now, Ford and Henry Fonda’s vision of Wyatt Earp is a little cleaned up. It’s idealized, but it’s valid because of it’s humanity. See, it didn’t matter if the real Wyatt Earp was in charge of a saloon that had call girls in there. It’s the way Fonda’s positioned in the frame and it’s his innate sense of being a human being that Ford brings out so beautifully.

In this scene, Wyatt Earp accompanies Clementine, who is Doc Holliday’s girlfriend, played by Kathy Downs. He accompanies her to a dance at a church being built in the town. And you can see just in the building of the church that civilization is coming to this town, and Doc Holliday and Earp and all the brothers and Ike Clanton, they’re all on their way out. Also, you can see what’s so beautiful about Wyatt Earp’s awkwardness with Clementine. She’s his friend’s girl. She’s very proper; he’s very rough, and he’s trying to be chivalrous. And you’ll see the way Ford frames it, and the dignity of the way these two people behave with one another, that these two things are inseparable, and they are inseparable from the scene’s visual composition and beauty. That will give you an idea. But there’s so much more to be said about Ford than has been. There are a lot of good books on him, too, on his work, on his life. ♦

To read Joseph McBride’s excellent piece on John Ford see here.

Irish Film & Television Awards

President Michael D. Higgins presented Martin Scorsese with the John Ford Award on February 25, 2017. The ceremony took place at a special Irish Film and Television Academy event in Dublin immediately after the renowned filmmaker delivered a key master class on Ford to IFTA members and filmmakers. Those in attendance received a first-hand insight into the work, technique, influences, and career of the renowned filmmaker – with film clips specially selected by Scorsese himself.

Speaking at the event, Áine Moriarty, CEO of the IFTA, said Scorsese “has transcended the very meaning of film with his explorations of humanity, conscience, and the collective human spirit.”

Accepting the award, the clearly delighted Scorsese, said, “To be honored by the Irish Film and Television Academy and to receive an award created in celebration of John Ford’s artistry and prestige, has great personal significance for me.”

Editor’s Note: This article was published in the April/May 2017 edition. To read Joseph McBride’s excellent piece on John Ford see here.

Thank you for published this article In your site and I hope you publish more about John Ford .

A person From Iran