For centuries, onchocerciasis, commonly known as river blindness, had plagued remote communities in Africa, Latin America, and Yemen. Lifelines for villagers, the rivers are breeding grounds for black flies that, when infected with a parasitic worm, transmit the disease through repeated biting. In return, those infected transfer the disease to uninfected flies who bite them, resulting in a plague characterized by extreme itching and eventual blindness.

That the simple chore of getting water in these communities is no longer as much of a danger as it had been for generations is due to William “Bill” Campbell, an Irish-born scientist who, with his colleagues at Merck Research Laboratories, discovered a novel therapy for treating the disease. In 2015, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, sharing it with Satoshi Ōmura of Japan.

It was in the late 1970s when, working with a batch of microbe strains that Ōmura sent over for evaluation, Campbell developed the drug Ivermectin (later named Mectizan) and suggested it would work for river blindness in humans. Not only did the drug work, it also proved effective against the parasite that causes elephantiasis, which co-exists with river blindness in many places.

More than 25 years later, since Merck made the drug free in those countries most affected, treating 250 million annually, the results speak for themselves. Several countries in Africa are making significant progress towards eliminating both diseases. In Latin America, three countries – Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico – have effectively eliminated river blindness.

The discovery, Campbell says, “Was a long process of finding a drug that worked against some worms, and then testing it against other worms, and following up with more testing, and more experiments. That involved a lot of hard work and a lot of persistence. Knowing enough about worms to draw analogies between the different types, and where they live and what they do, was a key factor.”

In terms of Merck making the drug available for free in poor countries, Campbell defers credit to the executives of the company after successful human trials done in collaboration with French tropical medicine experts in Africa.

“It worked just wonderfully well and the question then was what to do with it. As a pharmaceutical company, it would have been nice to sell it at a profit, but those most affected lived in poor countries, so there was no way people were going to get it unless it was donated,” he says.

“This decision was decided by the chairman and CEO of the company in conversation with a handful of three or four top associates, and I was not one of them. To my mind, they are the ones, and the only ones, who deserve credit for that donation.”

I met with Campbell at his cottage in Cape Cod last summer. At 86, I found him to be fit and trim with twinkling eyes, a keen mind, and self-effacing wit, as well as decidedly modest about his Nobel Prize.

“I think of it as an award in which I’m the representative of the Merck company’s research teams,” he said. The Nobel experience itself was “just out of this world,” he allows. “And then to meet President Obama was a great honor. I think the main positive [of being awarded the prize] is being contacted by people you haven’t been in touch with for many, many years and to know that people still remember you. In fact, the most positive thing is that people actually enjoy hearing about it. They actually get pleasure out of talking to someone who had [the Nobel] experience.”

At the time we met, Campbell was dealing with all the attention that being a Nobel laureate brings. “There is no way you can stop it from changing your life because there is just a constant barrage of invitations and letters and emails and requests. And while they are all wonderful to have, there are just so many of them and I am now very ancient and have no secretary or manpower or secretarial skills, it is stressful for me. Whether I say yes or no, it is just a constant preoccupation, especially if the invitation is from someone I know, and I have a lot of speeches to give and lectures to write.”

Since we spoke last summer, Campbell has traveled Ireland. He spoke at the Institute of Technology Sligo, then headed to Donegal for a homecoming reception in Ramelton, and following a few days break to visit with family, he traveled on to his alma mater, Trinity College Dublin, where a new fellowship, “The William C. Campbell Lectureship in Parasite Biology,” has been created.

We keep in touch by email, and he tells me that our Hall of Fame event is one of the last he will do. He’s looking forward to a return to a quieter life with his wife and family in North Andover, Massachusetts. He and Mary Mastin Campbell met at a church function in Elizabeth, New Jersey over 50 years ago, and she’s been at his side ever since. They have two grown daughters and a son, and family and grandchildren are an important part of their lives.

Campbell keeps fit playing doubles ping pong games, several times a week, enjoys solitary kayak trips in early morning, and the occasional hike up nearby half-mile hill. He spends much of his time painting and writing poetry, which reflects his passion for roundworms and other kinds of parasitic worms.

“I consider them beautiful,” he said. “They are just doing their own thing and not meaning to be destructive. And I have said in some recent papers that the objective is not to get rid of parasitic worms, the objective is to get rid of parasitic diseases.”

The American Society of Parasitologists has been a staple in Campbell’s life since he moved to Wisconsin in the 1950s. The society’s annual auction raises money to bring students to the meetings, and Campbell’s donated art, sees bidding wars that drive the prices skyward. He also helped create an award to recognize student achievement in parasitology.

Campbell has worked with both human and veterinary medicine because parasites are so integral to both. Among the other diseases he has helped eradicate is trichinosis, a disease that comes primarily from eating under-cooked pork.

“I gave a talk at George Washington University, in D.C., and at the end of the lecture, a young fellow put up his hand and said, ‘I heard that you once gave Scotch whiskey to pigs. Can you confirm that?’ And I said, ‘I never in my entire life gave Scotch whiskey to pigs. I gave them Irish whiskey!’ I fed the pigs seven-year-old John Jameson whiskey because of reports that alcoholic beverages would prevent trichinosis, and published a paper on it.” (It worked, he says, but “you would have to drink an awful lot of it. It would be a very expensive and hazardous cure.”)

Today, there is a big focus on using one’s own autoimmune system to target disease – some of the treatments use worms. “There is a connection between early childhood worm infections and a stronger immunity,” he says. “There is evidence that you can cure some diseases with worms. In some countries you can pay to become infected with worms as a cure for irritable bowel syndrome. It hasn’t caught on here because people are put off by the idea of worms. Most of the research, with a notable few exceptions, is being done on the fringe. Established researchers won’t touch it.”

He told Adam Smith, the chief scientific officer of Nobel Media, “There is a certain amount of hubris in humans thinking that they can create molecules as well as nature can create molecules in terms of the diversity of molecules, because nature consistently produces molecules that have not been thought of by humans.”

Campbell’s appreciation of nature is rooted in his childhood. He grew up in Ramelton, a small farming town in County Donegal, with two older brothers and a younger sister. Situated on mouth of the River Lennon, it is one of the most beautiful and remote spots in Ireland. His parents, Sarah Jane Campbell (née Patterson) of Dunfanaghy, and R.J. Campbell of Fanad, ran a general store supplying farmers. His father was a man ahead of his time, alway looking for ways to make improvements. “One thing that sort of typified my father was that he brought electricity to the Ramelton. He hired people to set up the poles and the wires to bring electricity to the whole town,” he recalls. His mother he describes as saintly. “I don’t use ‘saintly’ in a religious or liturgical sense, though she was devout, but rather to convey a sense of her profound goodness. She was very caring. I never heard her say a bad thing about anyone.”

In addition to running the store, Campbell’s father also farmed, raising shorthorn dairy cattle that won prizes at agricultural shows. It was at an agricultural show that 14-year-old Campbell picked up a leaflet on fluke worms in sheep that, in hindsight, may have influenced his interest in becoming a scientist. But then Campbell could just as easily have become a writer, an artist or a historian. His teacher during his formative years, Miss Martin, “instilled a love of learning, not in the sense of a chore to be mastered, but getting the satisfaction of knowing something, and remembering something. She had a tremendous influence on me,” he said.

Campbell’s path to becoming a parasitologist began in college, with Desmond Smyth, the renowned science professor at Trinity College, Dublin. “He changed my life by developing my interest in parasitic worms,” he told me. And Smyth was there again to make sure that his student took it to the next level.

“As I was nearing graduation, a professor at the University of Wisconsin wrote to Smyth in Dublin. They knew each other’s work, and as a result of this contact, I applied to do research and graduate studies at Wisconsin,” he says of the decision to move to the U.S. “When I got there, my professor had a project on liver fluke that he and his department were working on. This was the giant liver fluke that is very pathogenic in deer and sheep, so it turned out to be the perfect spot for me.”

Recruited by Merck out of school, Campbell stayed with the company for over 30 years, developing many significant drugs for humans and animals. But it is his hope that the future of science in medicine will be one free of chemicals. “We need to look at the immunological response and other biological approaches rather than chemical contrivances. We need to continue to work on other ways of interrupting life cycles and disrupting transmission of disease. One would hope that eventually [chemicals] would be replaced but certainly we are not anywhere near that yet, except in certain cases such as virus diseases,” he said.

After his retirement from Merck, Campbell taught undergraduate biology and graduate history at Drew University until 2012.

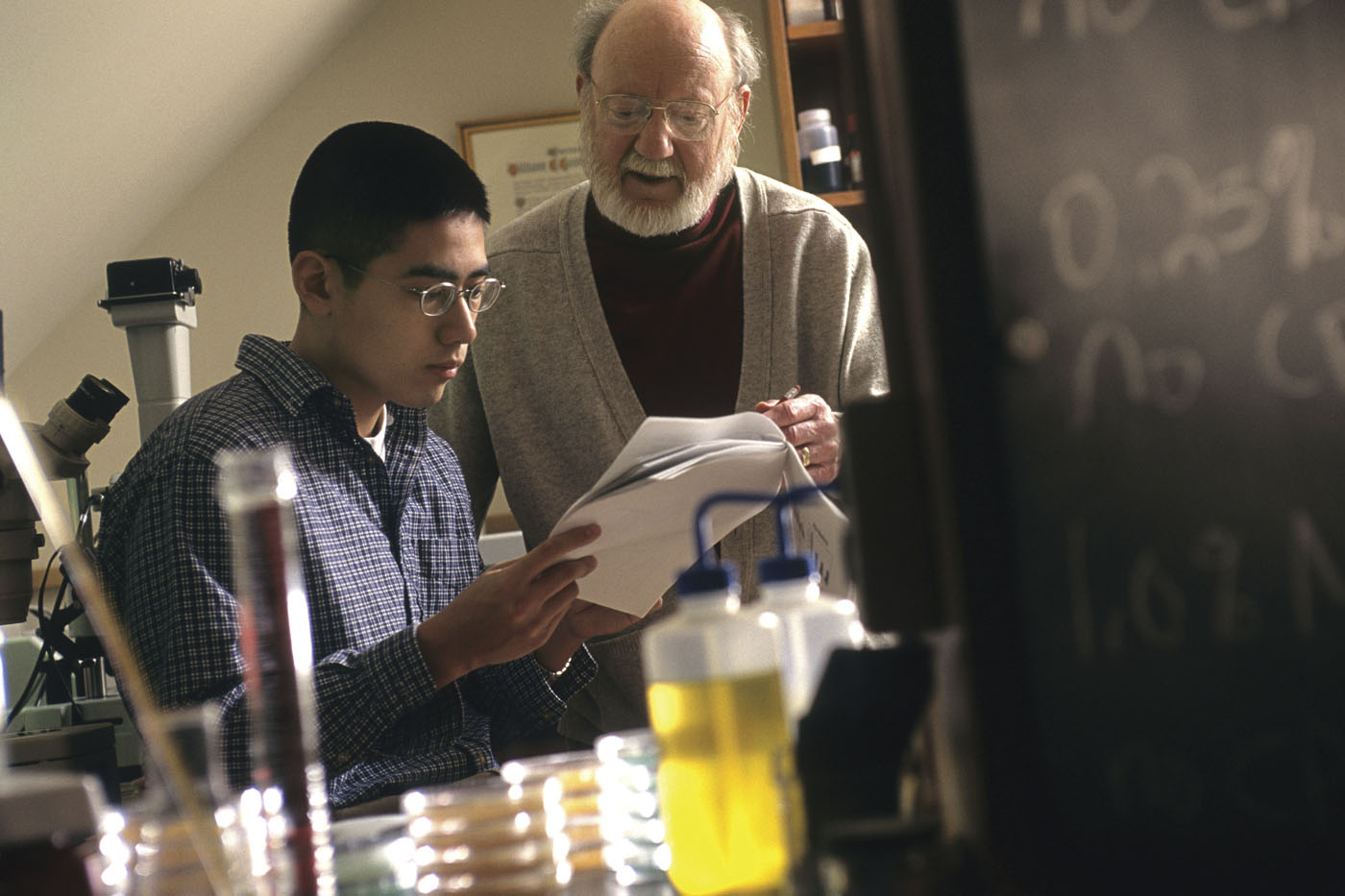

Former Drew student Manny Gabriel (see opening page photo), who just finished a fellowship at Roswell and will soon be working at the Mayo Clinic Florida, wrote to me of Campbell’s influence.

“Dr. Campbell was integral to my decision to becoming a physician scientist. It is amazing to me that my first publication was with him, but truth be told our initial submission was rejected. He told me not to worry and that this was simply part of the scientific process. A few short months later, he was right and our paper was accepted. Since then, I’ve had my share of rejected projects and papers, but each time I recall Dr. Campbell’s humble and practical words of encouragement. My two and a half years in the lab with him built up my perseverance and resilience, which is essential in this profession. I’m happy to say that his training has guided productivity and success in my academic pursuits. I am truly fortunate to have spent this time with Dr. Campbell, and am a better scientist and person because of it.”

As a teacher, Campbell often began his lectures by showing a picture of his father’s cows. “Of course it has absolutely nothing to do with the lecture, but I like to tell people where I’m from because it is such a part of me,” he said. When I remark that he still has a hint of an Irish accent after all this time in America, he laughs. “After about three days in Donegal, Mary says it comes back.”

“His lovely mother used to put together such wonderful picnics for us on Marble Hill beach,” Mary, who was an attentive host throughout my visit, adds. Campbell agrees. “I was very lucky to have had a great mother and a great father.” He pauses. “That’s one of those things about the Prize – you wish they were around.” ♦

Excellent & informative, very useful, inspiring WOW

William, Cecil, a cousin to be proud of.