Dave Lewis explores the historical connections between the Gaelic Athletic Association, nationalism, and a heritage of hurling in County Tipperary.

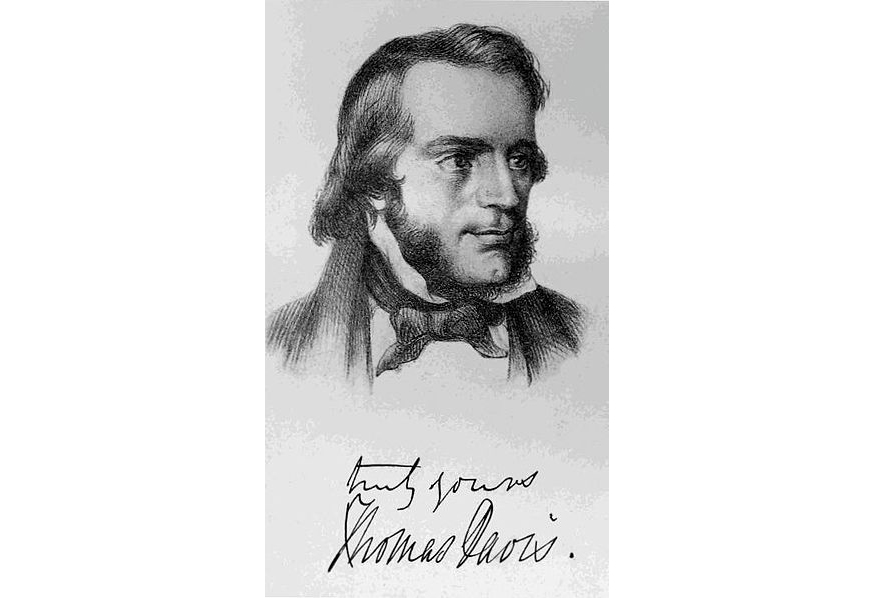

2016 was a great year for Ireland as it celebrated the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising. The year was an even better one for the people of Tipperary, as not only did they celebrate the heroes of the past, but celebrated two All-Ireland Championship victories. The men of the blue and gold achieved a hurling double in which both minor and senior county teams won the Irish Press Cup and the fabled Liam MacCarthy Cup. According to Eoghan Cormican of the Irish Examiner, the minors led by captain Brian McGrath defeated Limerick 1-21 to 17 points as Jake Morris scored a goal early in the second half. The senior team faced off against their rivals, Kilkenny, who were trying to retain Liam. Performances from Seamus Callanan, John “Bubbles” O’Dwyer, and John McGrath, were vital to Tipperary’s win as Callanan scored thirteen out of the twenty points Tipperary scored on the day while O’Dwyer and McGrath scored two great goals. The great Young Ireland leader, Thomas Davis once referred to Tipperary as the “Premier County” due to its nationalistic fervor in the 1840s and exclaimed, “Where Tipperary leads, Ireland follows.” Thomas Davis didn’t know it at the time, but this statement could not have been truer. The people of Tipperary have led in various aspects of nationalism throughout Ireland’s history whether it be through sport or military action. Tipperary were, and still, are the leaders.

℘℘℘

The Gaelic Athletic Association was founded on the first of November 1884 at Hayes’ Hotel in Thurles, Tipperary. It was Michael Cusack, a Clare man, who called for an “association for the preservation and cultivation of our national pastimes and providing national amusements for the Irish people.” Though Cusack was from Clare, four out of the original seven executive members were from Tipperary. These men were Joseph O’Ryan, J.K. Bracken, Thomas St. George McCarthy, and finally Maurice Davin. Michael Cusack personally selected Maurice Davin, from Carrick-on-Suir, Tipperary to be the Gaelic Athletic Association’s first president as Davin was an accomplished athlete. Davin had won multiple championships in field sports like hammer throwing and the high jump, and had an international following according to the G.A.A. Museum at Croke Park. Davin’s leadership on the field would develop off it as well. While the G.A.A. grew throughout the country, other organizations started to take notice of its recruiting potential.

℘℘℘

One such organization was the I.R.B. otherwise known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret revolutionary organization whose goal it was to overthrow British rule in Ireland and establish an independent Irish Republic. It was even rumored that the I.R.B. was in charge of the organization to start with as members began to take key positions in the executive officers’ positions. One of the key positions taken by an I.R.B. member was the vice presidency, taken up by another Tipperary man, P.T. Hoctor in 1886. Hoctor’s vice presidency brought the beginnings of the rumors that the I.R.B. was behind the G.A.A. as he pushed for I.R.B. leaders and Tipperary men like John O’Leary and Charles Kickham to be honored with patron-ship and memorial funds. One year later, Tipperary would be represented at the first All-Ireland Final.

For the previous four years, Gaelic games within the G.A.A. were played on a basis of challenge matches between local clubs within their own counties. That was until 1888 when the G.A.A. hosted the All-Ireland Championship on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1888. The two counties that were represented on the day were Tipperary and Galway. However, the teams were not set up how they are today, where players are selected from their clubs to be on the county team. From Tipperary, the Thurles Blues, known now as Thurles Sarfields represented Tipperary and Meelick, known as Meelick-Eyrecourt today represented Galway.

The game was also structured vastly differently than it is today. According to Ronnie Bellew and Dermot Crowe, authors of Hell for Leather: A Journey Through Hurling in 100 Games, the final was played in Birr, County Offlay. On the day, the Tipperary team dominated Galway as they came out as winners with a score line that read 1-01-1 to 0-00 as Tommy Healy drove the sliotar on his left side past the Galway goalkeeper, scoring the first-ever goal in an All-Ireland final, which meant that if Galway had scored a point, Healy’s goal would out- value that point. The third chronological point in the score line was also due to another rule that has since faded, the forfeit point, in which a player played the ball over his own end line. “The Premier County” men earned Davis’ moniker for them on the day.

While the G.A.A. had connections with the I.R.B. within their membership, the organization distanced itself from any kind of action that the I.R.B. had planned militarily. One of the foremost examples of this was during the 1916 Easter Rising, in which the G.A.A. wrote a statement that denied any involvement with the plans for the Easter Rising and even met with General John Maxwell, the British Army commander who oversaw the executions in the aftermath of the Rising, according to Paul Rouse of the Irish Examiner. Even if the executive members of the G.A.A. did not want to be involved with the IRB and its militant policies, their regular membership all throughout the country however made it their duty to take part in the Rising. Immediately after the Easter Rising, many members of the G.A.A. were sent to prisons like Frongoch in Wales, where the prisoners played hurling and football.

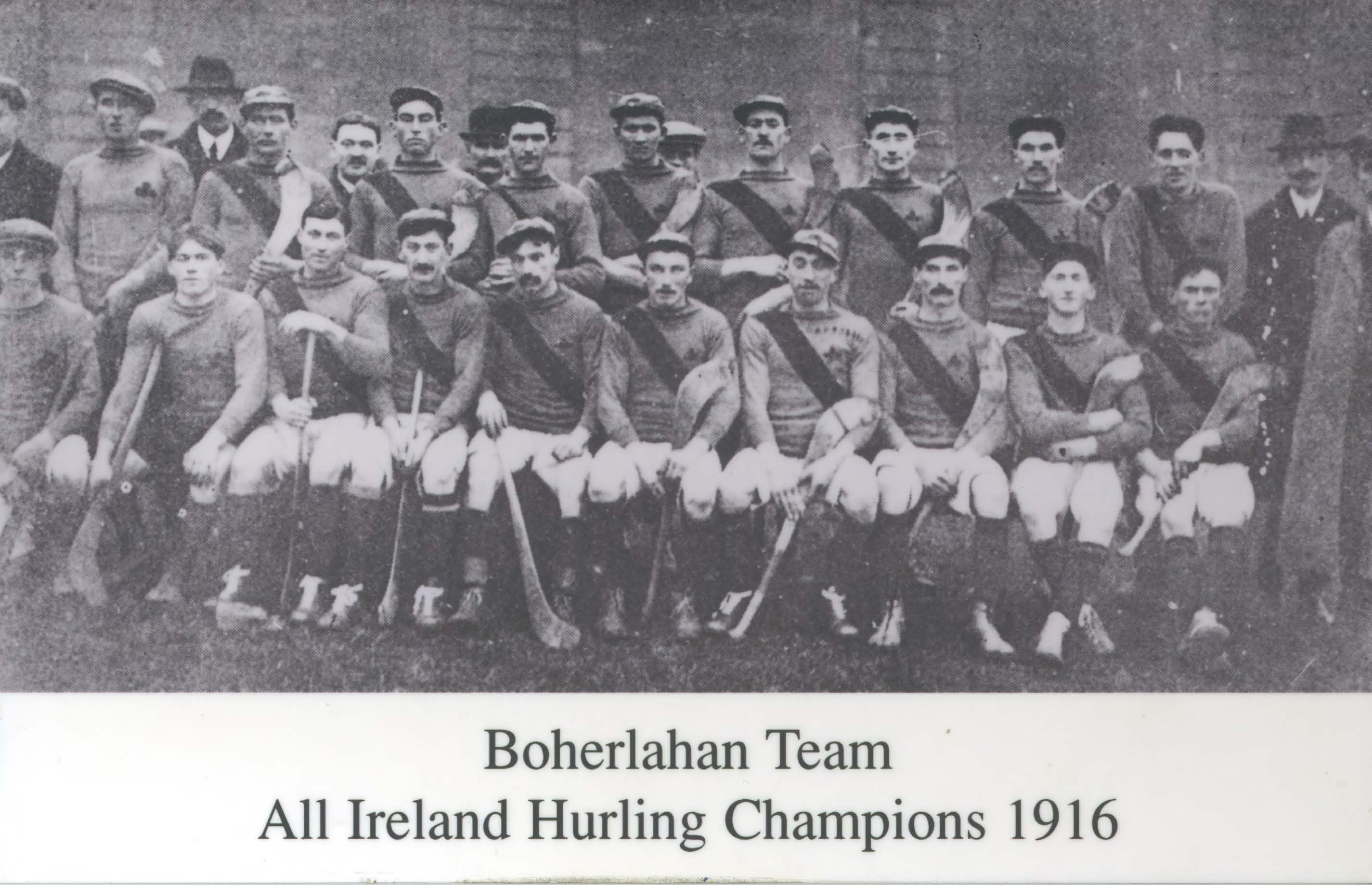

Gaelic games were still being played and despite the G.A.A.’s stance on the Rising, and its temporary loss of members, the Tipperary team still celebrated Republican heroes of the past as they had taken the field against Laois wearing green white and orange armbands that said “Remember Tone.” Even before the 1916 All-Ireland final (which was actually played on January 21, 1917 due to the internments of players and spectators), the men of the Premier County marched down Sackville Street and stopped at the GPO, the headquarters of the Rising, and recited a decade of the Rosary in honor of the rebels that valiantly fought for Ireland’s Independence there.

Their success off the field was matched by their track record on it, too, as they beat their neighbors, Kilkenny 5-4 to 3-2. Though people from Tipperary celebrated by lighting tar-barrels and marching through the town of Boherlahan to the beat of a Fife and Drum band, they would not be celebrating their team in three years’ time. Instead, they would be grieving at the loss of one of their own.

Three years later, Ireland was at war with England as Tipperary men Séan Treacy, Dan Breen, Séan Hogan and other members of the Third Tipperary Brigade of the Irish Volunteers ambushed two Royal Irish Constabulary, killing them. While the war was in its infancy, Croke Park was still the host to many exciting Gaelic football and hurling matches. While these matches were going on, Michael Collins, was planning an assault on British agents to smash their intelligence system. On November 21, 1920, very early in the morning, Collins sent out agents, his “Twelve Apostles,” to assassinate 14 British agents all throughout Dublin. As soon as British authorities were notified of the assassinations, British soldiers were sent to Croke Park to search the crowd to find those that participated in the killings earlier in the day. Tipperary and Dublin were playing in a challenge match when the Auxiliaries, Royal Irish Constabulary officers, and an armored car entered the stadium and started firing on the players and into the crowd. Fourteen people were killed including a 10-year-old boy, a young woman only five days away from her wedding day, and Tipperary right full back Michael Hogan while 60 were wounded. Hogan’s jersey on the day can been found in the Tipperary county museum today. Hogan’s death would be remembered in 1924 when Croke Park expanded the stadium and named its main stand after him. This tragedy would greatly impact the War of Independence, as it had shown the Irish people that the British forces within Ireland and the Crown cared little for the safety of the Irish people. Despite the fact that Hogan’s death was a tragedy, his death and the death of the 13 others led to a heightened awareness of how desperately the Irish people needed their freedom from the grip of its imperial neighbor.

℘℘℘

In today’s world, Tipperary still leads the way within the G.A.A. community in terms of impact. On February 25 this year, the members of Kiladangan G.A.A. are hosting a diasporic gathering at Slattery’s Midtown Pub in Manhattan. According to Colm Egan, originally a Kiladangan man but now living in Chicago as the chairman of the North American G.A.A. Hurling Development Committee, this event will be one of many happy reunions as 110-plus current members of the parish and expatriates from all over the world are coming to Manhattan. The goal, in addition to celebrating their common birthplace, is to help raise funds for a 6,000-square-foot community center for the local parish.

If you know of anyone from Kiladangan or the surrounding area, or anyone willing to help Tipperary keep its strong traditions, please tell them to attend! ♦

_______________

N.B. The Liam MacCarthy Cup, the traditional trophy of the All-Ireland Hurling Final, is named for Londoner Liam MacCarthy, born to Cork emigrants in 1851. MacCarthy was instrumental in the founding of the London county board of the G.A.A., of which Michael Collins and Sam Maguire (for whom the Gaelic Football All-Ireland trophy is named) were members.

The original trophy was made in 1920 and first awarded in 1923 due to the Irish War of Independence and Civil Wars delaying the 1921 All-Ireland hurling final. It was retired in 1992 when a replica was forged by James Kelly of County Kilkenny. Tipperary was the last team to win the original.

The design is based on that of a common communal domestic Irish medieval drinking vessel called a mathar, which would be passed between family members and guests by each of its four handles. Dave Lewis

O, lovely. Thank you for a fine and informative article. I sued to play hurley myself as a kid (at Ring College) before we emigrated. Then I played baseball.

Taugs dut.

Peadar Garland M. A. and enjoying it.

Besides the Liam McCarty Cup for the hurling champions, there is also the Sam Maguire Cur for Ireland’s Gaelic Football Champions every year, and the final for that trophy was played twicein 2016 because the first match between Mayo and Dublin ended in a draw, but in the replay, the Dubliners won by a point, 1-15 to 1-14 – and captured Sam Maguire. This trophy is named after a Corkman who was active against the Brits in the War of Independence. And like so many of our patriots, Sam Maguire was also a PROTESTANT.