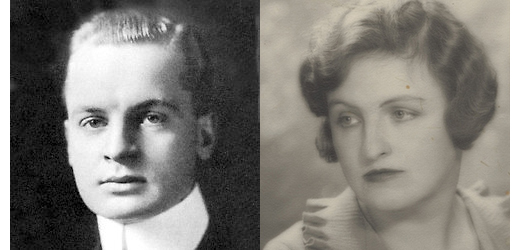

Gerald Murphy and his wife, Sara, were the golden couple at the center of glamorous expatriate life in Paris and the Riviera in the 1920s, with a social circle that included many of the great artists and writers of the day. Michael Burke goes behind the scenes to look at the dynamic Murphy family’s early beginnings.

Patrick: The Salesman

Patrick Francis Murphy, one of 13 children of Irish immigrant parents, born around 1855, turned out to be not only a natural born salesman, but also someone with a knack for marketing. He made a fortune that his children managed to run though in one generation.

Hired by Henry W. Cross,* first as a clerk and then as a salesman, for Cross’s saddle, harness, and trunk-making company, Patrick persuaded his employer (Cross was an Irish immigrant who had honed his saddle-making skills in London) to expand their equestrian merchandise to include small luxury items such as purses, wallets, and notebooks.

Sales took off and the business thrived. Murphy quickly became an integral part of the operation and eventually bought the business from Cross.

In 1892, Murphy proved himself far-sighted again when he moved his now upscale, luxury leather goods emporium to New York. New York had eclipsed Boston as the financial, cultural and social center of the country, and Murphy believed, it would be a more open venue for his business, and, at the same time, a place better suited for the social advancement of himself and his family.

Murphy leased space for his flagship store in the most fashionable section of town on the corner of Broadway and Murray Street, a building owned by John W. Mackay, the Irish-born silver miner and cable company magnate.

Murphy’s instincts were good and the store flourished. By 1893 there were two additional Mark Cross stores, one back in Boston and another in London. Later there would be one in Paris and another in Milan. But the market-savvy Murphy soon came to realize that the “horseless carriage” was here to stay and the need for equestrian equipment would drastically shrink. He therefore switched the focus of his operation. While retaining his signature luxury leather goods, he minimized riding equipment while adding various high-end pieces, including china, crystal, silver, decorative items and even some men’s and women’s apparel. Mark Cross soon became known for innovative goods such as cocktail shakers, liquor decanters, and even the first thermos. The stores also carried a full line of Scottish-made golf clubs. Later, during World War I, the firm introduced the first wristwatch. The company had always provided a mail order service, producing an extremely well put together catalogue, which literally came to be considered a work of art, as several volumes remain in the permanent collections of various museums today.

The Murphy family, Patrick, his wife Anna (née Ryan), sons, Frederick and Gerald, and daughter, Esther, were now wealthy. They had a house in one of the better sections of Manhattan and a summer home in the Hamptons.

Patrick’s outgoing personality made him a popular after-dinner speaker. Eventually he became so sought after that he attended and spoke at a different business dinner almost every night. He became a member of several important clubs, including the Manhattan Club and the Lambs Club in New York City and the Southampton Club on Long Island.

Patrick’s children, however, would remember him as a distant parent, and their mother Anna, as a strict Irish Catholic. Her son, Gerald, referred to her as a “Calvinist.”

Gerald: The Artist

As a young boy, Gerald was sent to Blessed Sacrament Academy on West 79th Street, but his mother decided that this school wasn’t strict enough and sent him to boarding school in Dobbs Ferry, New York where he said, “the nuns flogged me with wooden laths for wetting the bed.”

Fortunately, his college preparatory school proved a better fit. The Hotchkiss School, a private, nonsectarian, school in Connecticut specialized in getting its graduates into Yale, a service Gerald was in great need of.

As it turned out, both Fred and Gerald attended Yale. However, Gerald had to take the entrance exam three times before finally passing. Both sons were expected to join the family firm upon graduation. Fred, who had been sickly most of his life, dutifully obliged, although his weakened condition – exacerbated by his voluntary enlistment in the Army during World War I – often kept him away from work. He married Noel Haskins, a debutante from an old New York family and a close friend of his sister’s, retired from the company early and moved to France where he died in 1924. Noel remained in France for the rest of her life. They had no children.

Gerald had little interest in business, and decided to go his own way. His tenure at Yale was lackluster at best, his only distinction being accepted into various clubs, including the prestigious Skull and Bones. He was also at one point voted best dressed.

“I was very unhappy there,” he said of his time at Yale. “You always felt that you were expected to make good in some form of extracurricular activity, and there was such constant pressure on you that you couldn’t make a stand against it – I couldn’t, anyway.”

Gerald’s father considered him a disappointment, and often expressed this opinion. It didn’t help when he married, against his parents’ wishes, Sara Sherman Wiborg, who was five years his senior. (They met when he was 16 and she 20). Sara’s family had a summer home near the Murphy’s house in Southampton.

The Sherman Wilborg’s an established family (the American Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman was an uncle of Sara’s mother) whose wealth came from a mid-western ink-manufacturing business, also opposed the marriage.

The couple had their way though, and married in 1916. After an unhappy time working for his father, Gerald and Sara spent two years in Cambridge, where Gerald studied at the Harvard School of Landscape Architecture before they moved with their three children to France in 1921.

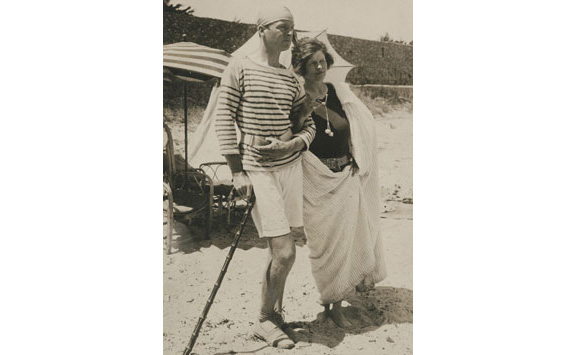

In both Paris and on the Riviera, Gerald and Sara entertained frequently and lavishly, soon winning many friends, notable among them Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, Jean Cocteau, John O’Hara, and a childhood schoolmate of Gerald’s, Dorothy Parker, among many others. Their social circle was extremely wide, encompassing at various points almost everyone involved in the arts and letters, including James Joyce.

They have been credited with innovating the “summer season” on the Riviera where they christened their house Villa America. Apparently no one had thought of using the Riviera as a summer playground before, only as a winter retreat. They were also credited with coining the term “sunbathing.” The pair figured prominently in much of the art and literature of the period.

Picasso, who seemed to have been somewhat smitten with the beautiful Sara, did five paintings of her. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is The Night is dedicated to them, as they were the original models for the characters Dick and Nicole Diver. Apparently, Fitzgerald was also smitten with Sara.

Despite their munificence to him during his struggling times, Ernest Hemingway would treat Sara and Gerald rather shabbily in his memoir, A Moveable Feast.

Years later, their friend, New Yorker magazine writer Calvin Tomkins, would write a book about them, entitled with the now familiar phrase, Living Well Is The Best Revenge.

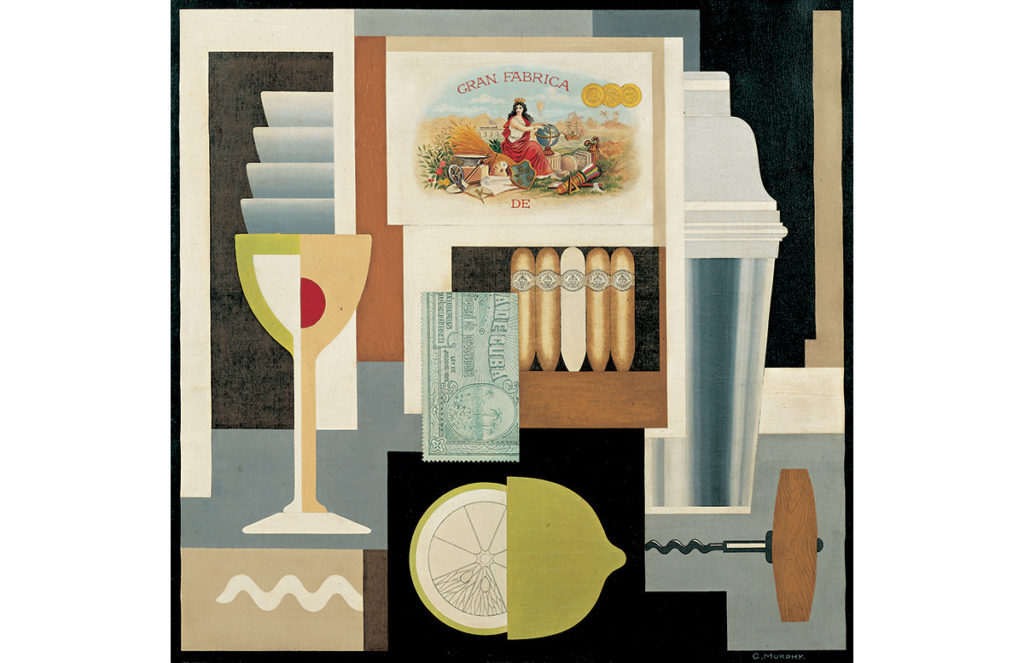

Sara and Gerald had come to know most of their European friends through the Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev. Soon after arriving in Paris, some of the company’s scenary was destroyed and they both volunteered to work as unpaid apprentices to help restore it. It was around this time, Tomkins writes, that Gerald started painting. “Walking down the Rue de la Boëtie one day, Murphy stopped to look in the window of the Rosenberg Gallery, went inside, and saw, for the first time in his life, paintings by Braque and Picasso and Juan Gris. ‘I was astounded,’ he says. ‘My reaction to the color and form was immediate; to me there was something in these paintings that was instantly sympathetic and comprehensible and fresh and new. I said to Sara, ‘If that’s painting, it’s what I want to do.’”

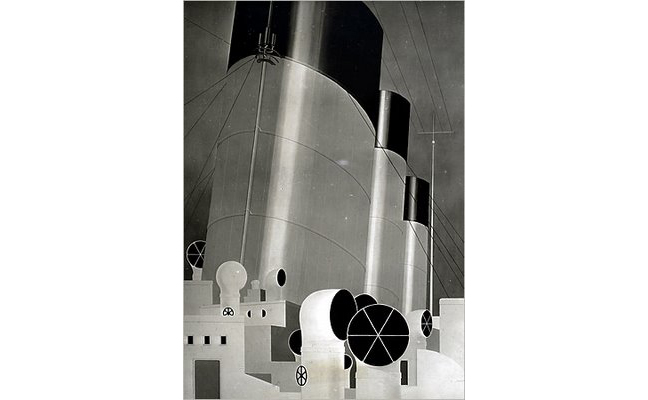

This was the beginning of Gerald’s career as a painter – a career that lasted for only seven years, but produced paintings that are now considered to be major works of American modernism. One entry into a Paris exhibition was the 18-by-12-foot painting, “Boatdeck” which, because of its size, made copy for three days in the Paris Herald. He also designed sets for ballets and co-wrote a ballet, Within the Quote, with his old friend from his Yale days, Cole Porter, that was performed in Paris in 1923.

Esther: The Heiress Who Loved Women

Perhaps the most unique and unusual member of patriarch Patrick Murphy’s family was his only daughter, Esther. Despite two rather strange marriages, she was openly gay for most of her life.

Although the Murphys were not actually in the upper echelons of the wealthy, Esther always thought of herself as an heiress, and behaved as such. She did not attend college and never worked. She did, however, possess a fine mind and her parents arranged for much of her education to be completed at home. Esther also seems to have had a photographic memory. Her social life was the most important thing to her and she attended numerous parties and events where she would dominate the conversation, expostulating on her views of history, politics and current events. She may have inherited her speaking ability from her father, along with a taste for alcohol. But while Patrick was known to overindulge occasionally, Esther did so frequently. However, she did manage to have many articles published and was considered a talented writer. Her last work was a biography of Madame de Maintenon, the secret wife of King Louis XIV of France, which she worked on for fifteen years and was still unfinished at the time of her death.

Esther’s love life, however, was an ongoing disaster. Her first husband, John Strachey, a cousin of Lytton of Bloomsbury fame, was an impoverished upper class socialist politician and early member of Britain’s Labor Party. Although he claimed to genuinely love Esther, he was open about marrying her for her money, demanding a large dowry from Patrick Murphy. He was elected to parliament, but his career was checkered and basically unimpressive, as was their marriage, which did not last long. The main love of Esther’s life was the fabulously wealthy American, Natalie Clifford Barney, one of the most influential American expatriates in Paris and an accomplished writer, poet, and playwright.

Natalie was an outspoken proponent of free love. Unfortunately, Esther’s love for her was unrequited. Esther had a rival at the time, the Irish born Dorothy (Dolly) Wilde, niece of Oscar. For some unexplained reason Esther decided to marry a second time. This choice was even more misguided than the first. She married Chester A. Arthur III, grandson of the late president, who used Gavin as his first name. Gavin may not have been of the best husband material but was an interesting person in his own right. He abandoned the successful lifestyle of his father and grandfather to pursue varied paths, including living in Ireland after quitting college and working for the Irish Republican movement in America, for which he was briefly jailed in Boston.

Although he was married three times, he was also openly bisexual. Esther and Gavin soon separated and were eventually divorced in 1961, but she chose to keep Arthur as her name for the rest of her life. The last romance of Esther’s life was with the writer Sybille Bedford, whom she met in New York in 1943. They traveled extensively together but gradually drifted apart, although remaining lifelong friends.

Esther died of a stroke on November 23, 1962 at age 65. Her story is chronicled in the multiple biography, All We Know, Three Lives, by Lisa Cohen.

A Sense of an Ending

Gerald and Sara seemed to be living an idyllic, carefree life until tragedy struck, with the deaths of their two boys, both in their teenage years. The boys had been named to honor Gerald’s Irish heritage. Patrick was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1929, which brought the family back to New York. But it would be their other son, Baoth, who died first, in 1935, after contacting spinal meningitis at 15. Two years later, Patrick died at 16.

Only their daughter, Honoria, who in the words of the Murphy biographer Calvin Tomkins, “looked like a Renoir and was dressed accordingly,” survived. Honoria attended Rosemary Hall School in Greenwich, Connecticut, and the Spence School in New York, and went on to work in the theater and act with Bernard Shaw’s muse, Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who created the role of Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion in 1914.

Honoria, who married Captain William Donnelly, a WWII war hero with whom she had two sons and a daughter, would later publish an account of her parents’ unusual lives, simply titled, Sara and Gerald. From her we learn that they never really overcame the loss of their two sons. While they remained in love and stayed married for the rest of their lives, they became somewhat distanced from each other.

Patrick’s illness was not the only blow that the Murphy family in 1929 suffered. Like so many others, the stock market crash hit them hard. Sara’s income was affected to some extent, but the Mark Cross Company suffered greatly as the demand for high-priced luxury items plummeted, if only temporarily.

In his will, Gerald’s father, who died in 1931, left control of the company to his long-time mistress, his secretary, Lillian Ramsgate. Whatever skills Ramsgate may have had, business management proved not to be among them. To prevent her from running the company entirely into the ground, Gerald, as chairman of the board, took over as chief operating officer. Surprisingly, he possessed enough business acumen to keep the company from going under, but it required a great deal of work, something he was unaccustomed to, but that he would have to do for much of the rest of his life. He held on to the company until 1948 when he finally sold it, but stayed on until retiring in 1955 at the age of 68.

Their once large fortune gradually shrinking, Gerald became ill with intestinal cancer. Sara remained by his side and was devastated by his death, on October 17, 1964 at the age of 76. She went to live in Washington, D.C. with Honoria and William, and died there in 1975 at the age of 91.

Artistic Acclaim

After his return to America in 1929, Gerald Murphy never painted again. But before his death in 1964, he would receive recognition for his work as an artist.

In 1960, his paintings, produced between 1922 and 1929, received their first exhibition in America when Douglas MacAgy mounted a show at the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Art.

In a letter to MacAgy, Murphy, then 63, wrote, “There is some-thing [sic] very reassuring (in a disorderly world) about knowing that there exists a catalyst-mentor who discovers and reveals that one had builded [sic] better than he knew. […] Most certainly you have been the kinetic force in the exhumation of those few canvases of mine. Where will it all end?”

Two more exhibitions of Murphy’s painting, at the Museum of Modern Art in 1974 and the Brooklyn Museum in 2008, renewed interest in Murphy’s work. Though he produced only 14 paintings (seven of which remain), he now has a permanent place in the history of American art. ♦

_______________

* Henry W. Cross, born in Ireland, learned the craft of saddle-making in London as a young man. After honing his skills in this trade, he immigrated to Boston, Massachusetts, and in 1845 founded his own saddle, harness, and trunk making business. He named the firm after his son, Mark W. Cross. The company was both a manufacturing and retail enterprise. The business prospered and soon, in addition to their own products, they were selling high-end equestrian leather goods imported from England. They were doing so well, they needed more staff. Among their new employees was an Irish American, Patrick Murphy, just 17 at the time, whom they hired first as a clerk and then as a salesman. The acquisition of this lad would prove to be a wise move.

The Mark Cross company was held by several interests over the years, until it was sold to the A.T. Cross Company (maker of the famous pens, but no relation), who expanded the operation to 23 stores. They, however, eventually closed the line and the Mark Cross name was finally brought to a close in 1998, after 151 years. The brand was revived in 2010 and is now available through Barney’s New York.

Another wonderful article in this issue! Bravo Irish America. Again coincidentally I am researching the Mackay mentioned, also for an Irish American article. By the way, I believe that “Living Well Is the Best Revenge” is a quote from Oscar Wilde. I have read about the Murphys peripherally before; now you make me want to real a full bio. What a wonderful career – to think that Gerald Murphy produced all that fine art also. Life is mysterious. Glad you gave Hemingway what he deserves. Thanks!

A nice article about people I have read a lot about. I got interested in the Murphy’s after seeing them portrayed in the biopic movie about Cole Porter called “D’Lovely.” I have read everything I could find about them and you have added to that. Thank you.