Ireland’s ancient Christmas traditions and the magic of Newgrange.

The winter holidays are a time to gather with family and friends, to share abundance, to feast, to reflect on joyful memories, and to hope the future will be peaceful and prosperous for all. It seems someone is slicing a fruitcake or pouring a glass of holiday cheer wherever one goes. Bombarded as we are by Madison Avenue merchandising, it’s easy to forget that we are participating in one of humanity’s oldest rituals.

Eons before the birth of Christ, the sun’s movement through the heavens was a wondrous cycle. Our ancestors planted crops in the spring, nurtured them through summer and reaped the harvest in fall. Winter was another matter. Daylight waned, cold winds blew, and plants withered. Food ran out and people starved. Perhaps the sun might disappear altogether and plunge the world into eternal darkness. Hoping to prevent this calamity, early humans honored the sun with ritual and ceremony on the shortest day of the year, winter solstice.

Many nations have famous ancient solar observatories: Egypt’s Great Pyramid, Mayan Mexico’s Temple of the Sun, England’s Stonehenge. Few know that earth’s oldest sacred sun site stands in Ireland. Less than an hour’s drive from Dublin, massive Newgrange* in County Meath has been a silent sentinel of the sun’s celestial journey for more than five thousand years.

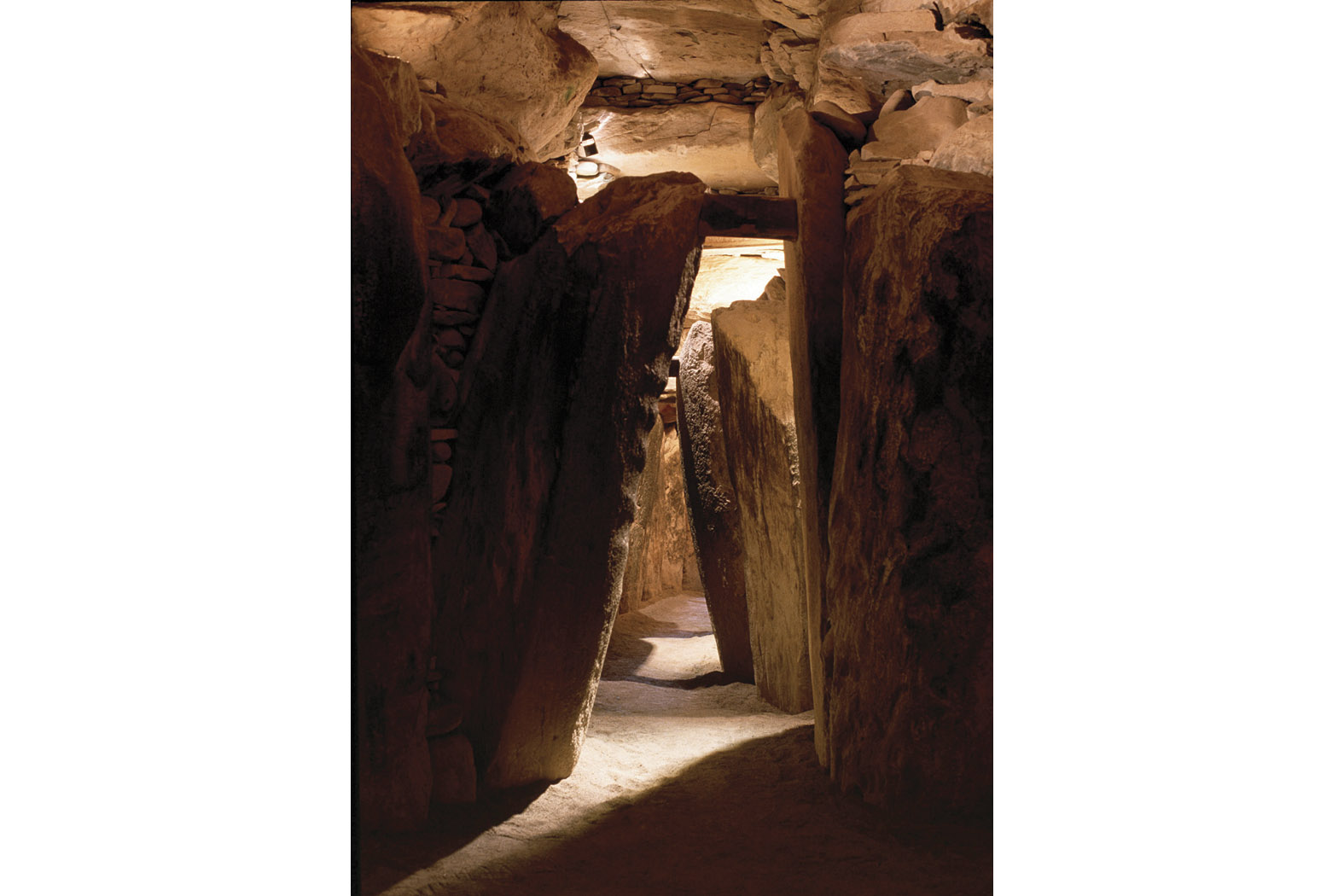

Long ago, people gathered there in the inky black of the mid-winter night, waiting to honor the sun. The southeastern sky would brighten, heralding its approach. Then, as the golden orb rose over the horizon, the first ray of sunlight passed through a small opening over the mound’s entrance, crept down a long narrow passageway, illuminated the inner chamber and slowly crept out again as soundless as it had come. The phenomena and ceremonies that took place at Newgrange indelibly marked our ancestral memory.

By the time Christianity became Europe’s dominant religion, winter solstice observances were so firmly fixed in the lives of the continent’s populations, there was no getting rid of them. Since the date of Christ’s birth was unknown, the Church decreed December 25 as the Feast of the Nativity. In a way, it made sense. Winter solstice revelries honored the sun god’s light. The Christ child was the son of God and the “Light of Redemption.” With hardly a blink, ancient pagan rituals were incorporated into the new faith’s celebration.

When Rome brought Christianity to Ireland, sacred druid symbols were absorbed and still adorn homes in this day and age. Plants that magically remained green all year now drape windows and mantles. Holly that bore red fruit amid winter’s snow was considered a fertility symbol. Today, it decks the halls. Mistletoe that thrived in the skeletal branches of oak trees was so revered that when enemies met beneath it, they cast off their weapons and embraced in peace. It became our delightful kissing ball.

The purpose of winter solstice festivities had been to dispel fear of the dreaded dark. In homes and public places, lamps, candles and hearth fires blazed forth. People put aside chores and made merry. In the 17th century, when Ireland felt the hammer blow of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan iron fist, everything changed. From cities to hamlets, town-criers chanted “No Christma-a-as!” Decorative greenery was dismantled and burned. Revelry was forbidden. Priests were imprisoned. But the Irish celebrated despite the hazard.

Those troubled times launched the custom of putting a candle in the window on Christmas Eve. Primarily, the candle’s flame symbolized “welcome” to Mary and Joseph, who sought shelter on the first Christmas night in Bethlehem. It also signaled that any priest could secretly and safely say Mass in that household. In our time, one candle has multiplied to hundreds of glittering lights on the eaves and window frames of homes during the Christmas season.

Another Christmas Eve tradition based on Mary and Joseph’s fruitless search for shelter was common practice in many Irish homes. After the evening meal had been cleared, the front door was unlatched and the kitchen table was set with a pitcher of milk, a loaf of bread studded with raisins and caraway seeds, and a lighted candle. This offering of hospitality to the holy family, or any other wayfarer who might be traveling on the “Night of Nights,” birthed another modern tradition – the cookies and milk children set out for Santa Claus.

Baking fruitcakes begins in late October when grocery shelves fill with spices, sultana raisins, and candied fruit peels. Regularly doused with whiskey, the fruitcakes age until a week before the holidays. Then, they are covered with sheets of almond marzipan, iced with snow-white royal frosting, and decorated with holly designs cut from candied citron and cherries.

Three fruitcakes were usually prepared months in advance. The first, served at midnight on Christmas Eve with glasses of whiskey and cups of tea, marked the beginning of the season’s 12 joyous days. The second appeared at midnight on New Year’s Eve, accompanied with similar liquid refreshment and wishes for a prosperous new year. The third cake was saved for Women’s Christmas. Better known as the Feast of the Epiphany, it marks the twelfth day after Christ’s birth when Mary carried her son to the temple to be blessed by the elders.

During the season, Irish kitchens also bloomed with the scent of two other delights – seed cakes and mincemeat pies. Seed cakes were speckled with caraway seeds, a common medieval spice. Mincemeat, another specialty of the Middle Ages, originally included chopped meat and suet, but today is a mixture of chopped apples and nuts, candied citrus peels, raisins, lemon juice, wine, brandy, and spices representing the exotic gifts of the Magi.

As with all holy eves, December 24 was a fast day and people were forbidden to eat meat. For the night before Christmas dinner, even poor families managed to acquire a bit of fish that was stewed with vegetables in a thick cream sauce. After dinner, small seed cakes were distributed, and woe to anyone whose cake crumbled before tasting, an omen that augured bad luck for the coming year.

Oliver Cromwell forbade making mincemeat pies for two reasons. Originally baked in an oval crust representing Christ’s cradle, Cromwell considered the form a heretical use of a sacred image. The ban also condemned the pie’s rich ingredients and liquors, sinful indulgences that Puritan dogma prohibited. After the Restoration, the pastries became legal again, but during the forbidden years Irish women risked imprisonment by continuing to bake mincemeat pies for secret Christmas celebrations.

Except for the oppressive Cromwell years, Irish church bells have always rung on Christmas Eve. For centuries the bells began tolling at 11 o’clock and ended with the 12 strokes of midnight. Known as “the devil’s funeral knell,” the practice echoed the folk belief that Satan died when Christ was born and the sound would protect their parish from evil for the next 12 months. Bells still ring, but only to call the faithful to midnight Mass and announce the start of the joyous season.

New Year’s Eve is when one of Ireland’s national treasures is most appreciated. For then, we raise a glass of uisce beatha (“water of life”) and wish a year of good fortune to all. Though we Irish have many toasts, here’s one of the best for sharing: “Health and long life to you! Land without rent to you! The mate of your choice to you! A life of peace to you! And may you be half an hour in heaven before the devil knows you’re dead!” In this and every season. Sláinte!

RECIPES

Mince for Pies

(Personal recipe)

3⁄4 lb mixed tart apples (peeled, cored, & chopped)

1 tbsp minced candied citrus peel

2 tbsp slivered almonds

2⁄3 cup halved seedless grapes

11⁄2 cups raisins

11⁄2 cups currants

3⁄4 cup golden raisins

grated rind and juice of 1 lemon

1⁄2 tsp ground cinnamon

1⁄2 tsp ground allspice

1⁄4 tsp freshly grated nutmeg

1⁄2 cup light brown sugar

2 tbsp melted butter

1⁄2 cup brandy

Mix all the ingredients together, cover and place in the refrigerator until ready to use. Keeps one month. If you have some left over after making your pie, it’s delicious stirred into hot oatmeal for a special breakfast treat!

Mince Pie

(Personal recipe)

2 cups all-purpose flour

1 tsp salt

11⁄2 tsp baking powder

1⁄2 cup olive oil

1⁄2 cup very cold water

1 egg yolk

2 tbsp milk

Dough: Mix the dry ingredients and set aside. Mix the olive oil and water then pour into dry ingredients. Use a fork to stir the ingredients together.

Divide the dough in half, wrap each piece in plastic wrap, and chill in refrigerator for 2 hours. When ready to bake your pie, roll each piece of dough into circles at least 2-inches wider all around than your pie pan.

Transfer one circle of pastry to a 8-inch pie pan leaving a 2-inch overhang. Mound the mince in the center and cover with the second piece of dough. Cut a few 1-inch steam holes in the top pastry. Tuck the edges on the pastry under and make a decorative fluted edge. Combine egg yolk with cream and paint the pie’s top surface. Bake at 350F for approximately 40 minutes, or until the pastry is golden and the fruit has released its juices. Remove pie to a wire rack and cool at least 4 hours or overnight before cutting. Serves 8-12. ♦

_______________

*Newgrange, Co. Meath

Newgrange, the Neolithic monument in the Boyne Valley, County Meath, was built approximately 3200 B.C. and predates by many centuries every other ancient solar site on Earth. Rising 39-feet high, covering an acre of land, and containing over 200,000 tons of material, its astounding size testifies to the engineering genius of its Stone Age builders. Ringed by 97 immense “kerbstones,” many engraved with artwork, the massive structure’s primary feature is a 61-foot-long passageway leading from the entrance to three adjacent interior chambers.

For millennia, Newgrange lay undisturbed, its mounded presence merely a stimulus for legends about the mythical Tuatha Dé Danaan. Then, on December 21, 1967, archaeologist Michael J. O’Kelly happened to be examining the inner chamber before dawn and became the first person in modern history to witness the extraordinary sunrise event. For the next few years O’Kelly returned to Newgrange daily in the pre-dawn hour, ultimately confirming that the solar phenomena occurs only on the five days surrounding the winter solstice.

Access to Newgrange is by guided tour exclusively from the Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre. To experience the winter solstice phenomenon from inside Newgrange, one must enter a Visitor Centre lottery. At the end of September, 50 names are drawn, 10 for each morning the chamber is illuminated, with two places awarded to each winner. More than 32,000 people entered the lottery to witness the 2016 winter solstice. For more information, visit newgrange.com/visitor.

This article was originally published in the December / January 2017 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply