It sure was big news when Pope Francis, the first Latin American pontiff, was chosen. And there has been talk about the prospect of having a black or Asian pope. But amid the widening papal radar, Ireland goes overlooked. Despite the nation’s overwhelming Catholic majority and hard-fought Catholic tradition, no Irishman has likely ever come close to the top position.

In 2012 the Irish Independent ran a very brief piece saying that a St. Killian from County Cavan was offered the papacy around 680 A.D. but declined (the papacy wasn’t then as coveted a position as it is now) because he wanted to continue his proselytizing in Germany. However, there is no mention of Killian (also spelled Cillian) being offered the papal position in the New Catholic Encyclopedia (second edition), which describes his journey to Rome and meeting with the Pope as “certainly unhistorical.”

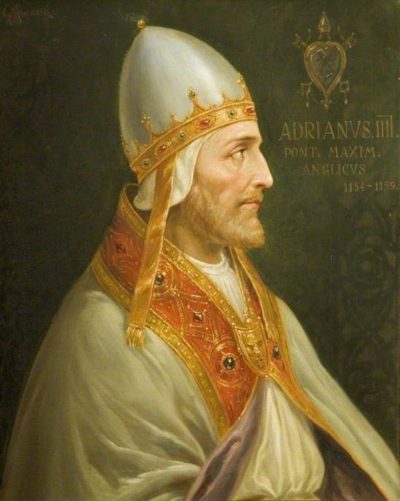

Of 266 popes listed on the Guardian’s website, about 200 have come from Italy. The second-most common ethnicity has been French, with 15 popes. About a dozen came of Greek origin, about a half-dozen of Syrian origin and the same number for Germany, which was represented by the previous Pope, Benedict XVI, who resigned in 2013. Technically there have been a few popes from the African continent, but they were essentially Romans living in North African colonies. There have been three popes of Spanish origin, and two who came from Portugal. Poland was represented recently with Pope John Paul II. Even Britain has had a pope (Adrian IV, in the mid-12th century*). But no Irish pope to speak of.

The absence of any Irish-background pope doesn’t appear to trouble too many souls in Ireland. “I don’t think it bothers anyone,” says Maolsheachlann O’Ceallaigh, who works in the University College Dublin’s James Joyce Library and runs the blog Irish Papist (irishpapist.blogspot.com). “I’ve never heard anybody complain about it, or even anyone wonder why we have never had an Irish pope. We didn’t have an Irish cardinal until 1866 [Cardinal Paul Cullen], and there was no Irish saint canonized for hundreds of years before St. Oliver Plunkett in 1975. So maybe pope just seems way above our expectations. Ireland does seem to have punched strangely below its weight considering its reputation as a Catholic country, but we don’t seem to think about it that much.”

O’Ceallaigh adds, “Perhaps we felt that if England only had one [pope], it wasn’t so strange for us to have none. When Pope John Paul II was elected the first Polish pope, it was seen as a marvel. Polish and Irish Christianity are often seen as similar, so I think this adds to the feeling that ‘getting a pope,’ for a small nation, is a bonus rather than something to be expected. Indeed, there was almost the feeling that J.P. II was an ‘honorary Irish pope,’ as the two countries had such similarities in terms of history and popular piety.”

Asked if he thinks there’ll be a pope of Irish descent in the 21st century, O’Ceallaigh acknowledges his temptation to say, “I hope not.” His reason is that as Catholicism is becoming increasingly represented by African and Asian nations, it would be more suitable for popes to be drawn from such nations. He sees no pope-able candidate in the current Irish Church hierarchy, but thinks that the chances may be better for an Irish American pope. He feels that Wisconsin native Cardinal Raymond Leo Burke, the current Patron of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, would make a “great” pope.

Right after Pope Benedict XVI announced his resignation, the International Business Times ran an article saying that Dublin Archbishop Diarmuid Martin – who has been widely touted for his assertiveness in taking on the issue of clergy sex abuse – had a one in 66 chance of becoming the next pope (the odds were set by the Irish bookmaker Paddy Power). Chances for New York’s Cardinal Timothy Dolan becoming the next pope were put at one in 25.

But in the view of acclaimed historian, novelist and speechwriter Peter Quinn, author of Looking for Jimmy: A Search for Irish America and purveyor of newyorkpaddy.com, Cardinal Dolan has “zero chance of being pope.” He feels that Boston’s Cardinal Seán Patrick O’Malley is a “far more likely candidate,” explaining that current Pope Francis picked O’Malley over Dolan when forming a council of advisors. Quinn adds that, “O’Malley shares Francis’s desire to enlarge the role of women in the church, which has to be a priority for any future pope.”

In his “nearly 70 years,” Quinn never heard anyone he knows express dismay over Paddy’s papal absence. He says, “The focus was always on having an Irish American president, an aspiration fulfilled by JFK. The Irish Americans I grew up with in the Bronx were always happy with Italian popes.”

Current differences within the Church have little to do with ethnic background and more to do with the extent to which Catholic orthodoxy should be applied to current daily life. As Quinn says, “Catholic liberals would be delighted with a progressive; Catholic conservatives with a traditionalist. A number of women would only be happy if the first Irish American pope is a woman.”

In Quinn’s view as a practicing Catholic, “What matters is the character of the pope and his embodiment of the humility and compassion central to Christianity. I don’t want to see a reactionary as pope, whether he’s Polish or Irish or Zambian. I think Pope Francis is a wonderful pope and a role model for those who follow, no matter their nationality.”

Apparently, pope-less means anything-but-hopeless for the Irish. As O’Ceallaigh points out, “I think Irish Catholics are very proud of their contribution to the Church, especially as regards evangelization, and other matters such as the innovation of private confession (which came from Ireland). So we don’t really feel any sense of being marginalized.”

And so, Irish Catholicism marches on proudly in this modern era, regardless of whether an Irish pope ever need apply. ♦

_______________

Ray Cavanaugh is a freelance scribe from Massachusetts. His mother comes straight from Kerry, and his father is a few generations removed from Wexford.

_______________

*Adrian IV: The Culprit

Mentioned above is the sole English pope, Adrian IV (below), the culprit who gave Ireland to England in an 1155 Papal Bull. The pope dispatched King Henry II and his troops over the Irish Sea to enforce British rule but Archbishop Lawrence O’Toole of Dublin intervened, negotiating a treaty between the Irish and the invaders. The king soon violated the treaty and Ireland’s freedom ended, 800 years of misery began, and Lawrence O’Toole died of a broken heart. While O’Toole was quickly – in 1225 – canonized, the “Isle of Saints and Scholars” did not produce another saint until 1975 when Blessed Oliver Plunkett, after a very long wait, received the official nod. In those intervening 750 years, the Catholics of Ireland were persecuted and martyred for their faith as centuries of suppression only fueled their spirit. Holy men and women were denied sainthood, a mysterious snub since the early Church in Ireland brought forth so many bold, poetic, mystical saints – Patrick, Brigid, Columba, Ita and so many more. Vatican inbreeding can explain the papal exclusion but can’t explain the lack of saints in the most fervent Catholic country in Europe. A sorrowful mystery for sure.

– Rosemary Rogers, author of Saints Preserve Us!: Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need.

Note: This article was originally printed in the December / January 2017 issue of Irish America.

Popeless/hopeless pretty good. As for the current pope (Francis?) he just seems a publicity seeker and a busybody.