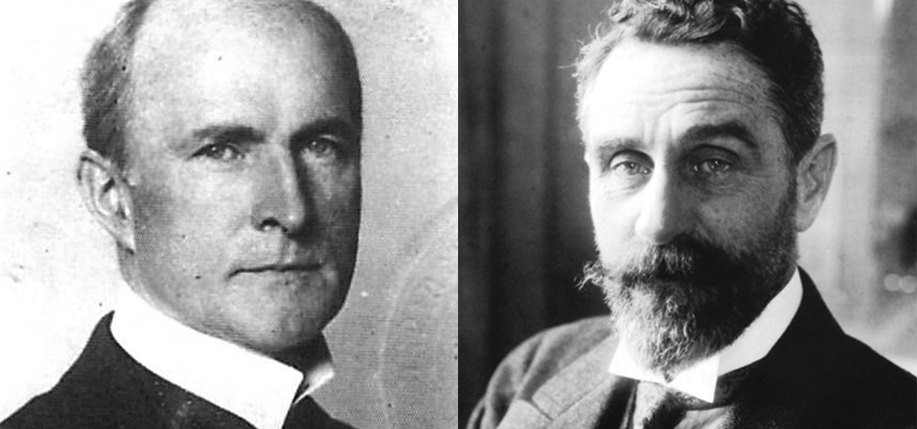

John Quinn, the lawyer who funded the Irish literary renaissance by supporting Ireland’s leading writers of the day (including W.B. Yeats and James Joyce), is less well-remembered for his involvement with Irish nationalism and his friendship with Roger Casement, the Irish-born diplomat who was knighted by King George V in 1911 and executed for his role in Ireland’s Easter Rising in 1916.

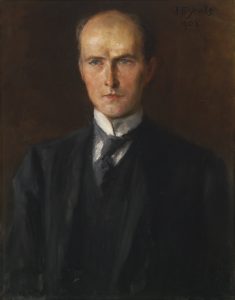

John Quinn defies easy categorization. The son of Famine-era immigrants, he was born and raised far from Irish American urban centers like New York and Chicago in Fosteria, Ohio. At 19, he left Ohio to serve as a private assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury. From there, he leapfrogged to Harvard Law School. Still in his mid-20s, he descended on New York in what his biographer describes as “Algeresque fashion” to make his fortune in the thickets of corporate law. Undeterred by barriers of religion, ethnicity, and class, he did so in rapid fashion.

Quinn is primarily remembered as a pioneering, perspicacious advocate of literary and artistic modernism. A close friend of Ezra Pound’s, he purchased original manuscripts from James Joyce, Joseph Conrad, T.S. Eliot, and W.B. Yeats, in the process serving as supporter and patron. He defended Joyce’s Ulysses in the New York courts against obscenity charges. Among the earliest American collectors of the works of Van Gogh, Picasso, Matisse, Brancusi, et al., he sponsored the Armory Show of 1913, a turning point in the history of American art that shocked New York audiences and raised public awareness (if not acceptance) of abstractionism and the avant-garde.

Less well remembered is Quinn’s involvement with Irish and Irish American nationalism. Whatever social disadvantages or prejudices he might have faced, he made no attempt to disguise or distance himself from his Irishness. Neither did he try to hide his contempt for what he saw as the narrow-minded provincialism and cultural parochialism prevailing in much of Irish America. He was especially bitter over the raucously hostile reception of J.M. Synge’s masterpiece The Playboy of the Western World, a controversy that left him with a lasting animus toward “that old fool,” John Devoy.

Quinn took a keen interest in the reinvigorated effort of the Irish Parliamentary Party to bring about Home Rule. He fulminated over the uncompromising militancy of Sir Edward Carson and the Unionists, while at the same time decrying John Redmond’s cautious, irresolute response as certain to encourage “braggarts, boasters, and treason mongers.” Quinn’s position never changed. He supported a united, self-governing Ireland that maintained its tie to Great Britain. In 1922, at the outbreak of civil war over the Anglo-Irish Treaty, he wrote to Douglas Hyde, “I would not shed the blood of a single Irish wolf-hound for the difference between a republic and free state.”

Despite his adamant opposition to physical-force nationalism, when Padraig Pearse paid a visit to him in New York, Quinn was taken by his intellect and sincerity. “However much one may differ from his political beliefs,” he wrote in the wake of Pearse’s execution, “one must admire his ideality [sic], his undaunted spirit, and the purity of his motives.” Quinn’s initial reaction to the Easter Rising itself was less kind. A staunch supporter of the Allied cause, he found himself depressed and repulsed “by the horrible fiasco in Ireland.”

The execution of the Rising’s leaders affected a change. Quinn’s nationalist sentiments, stoked by British intransigence and the courage with which Pearse and his companions went to their deaths, were ignited by the fate of Sir Roger Casement. Quinn met Casement in 1914 when he came on a fundraising trip for the Irish Volunteers. An admirer of Casement’s idealism as a defender of human rights in Africa and South America, Quinn hosted him in his apartment and put him in touch with potential sources of funds.

Though their friendship was tempered by Quinn’s dismay at Casement’s unabashedly pro-German sympathies, the death sentence handed down in an English court led Quinn to put aside his enmity for the Central Powers and mount a campaign to spare Casement from hanging.

Casement’s treason in trafficking with Germany, Quinn argued, had to be balanced against his motives as an Irish patriot. Quinn wrote a long memorandum to the British Foreign Office arguing for commutation of Casement’s sentence. He gathered the signatures of prominent Americans and pressured the State Department to send a cable.

Quinn’s efforts were to no avail. Casement was hanged in London’s Pentonville Prison on August 3, 1916. Ten days later, on August 13, Quinn published an elegy in the New York Times Magazine in which he wrote:

“Roger Casement is dead. Tried in an English court upon the charge of treason, convicted by an English jury, sentenced by English judges, judgment affirmed by an English court of appeal, hanged in accordance with English law, his body buried in quicklime in a nameless grave, his case is now transferred from the English courts and English public to the court of history and to the judgment of the world.”

Soon after the execution, Quinn learned that in the interests of dampening calls for sparing Casement’s life, the British government had stealthily circulated diaries detailing his “degenerate” behavior as a closeted homosexual. Furious at what he saw as a vile smear directed against his dead friend, Quinn threatened to take the matter public and expose the diaries as forgeries.

Presented with convincing evidence the diaries were authentic, Quinn dropped his plan. Still, he wondered, how did Casement’s private sexual behavior justify his being hanged for high treason?

For his part, John Quinn never renounced Roger Casement’s friendship. He never recanted his admiration nor questioned the sincerity of Casement’s sacrifice. He knew the man’s courage and the cause he sacrificed his life for. Was Casement a patriot or a traitor? Was he one with those in the Dublin GPO whose “excess of love bewildered them till they died?” Was he to be numbered in their song? John Quinn had little doubt about what final judgment history and the world would reach. ♦

Form more about John Quinn read The Mighty John Quinn, Defender of Ulysses.

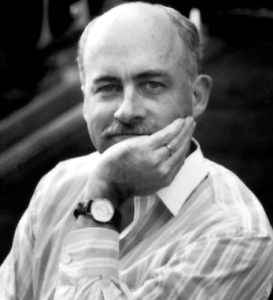

Peter Quinn is the author of several books, among them the acclaimed novel Banished Children of Eve. He previously served as a speechwriter for two New York governors. After years as the corporate editorial director for Time Warner, he is now a full time writer.

“HOUR OF THE CAT is the hour of Peter Quinn’s genius. It’s been said a million times but I’ll say it again: ‘I couldn’t put it down.'” —Frank McCourt.

For more information on Peter Quinn see newyorkpaddy.

Tom Deignan interviewed Peter Quinn for Irish America in 2021 when the Banished Children of Eve was re-released.

Well, this is a coincidence as I happen to be reading Reid’s The Man from New York Pulitzer Prize-winning bio of Mr. J Quinn. Great fun, especially after just having read Prodigal Father, Murphy’s phenomenal bio of the artist John Butler Yeats who also had four amazing sons and daughters. As an Irishman and a writer myself, I salute you Mr. Quinn on a really professional article. I will soon submit an article myself to Irish America on John Quinn’s mentoring of W B Yeats. Hope I’m as successful as you were with your article. Are you a relation to your subject? What else have you written?

Best wishes, Peter Garland

Peter Quinn writes above that Quinn was presented with convincing evidence that the diaries were authentic. I should like to know what form this evidence took and also what Quinn’s response was.

not sure if I sent this or not so here it is (encore)

The evidence was in the handwriting, which JQ compared with that of letters from his friend, Roger Casement.

I think Peter Quinn tells us that J Q’s response was to drop plans to expose the diaries as forgeries. He’d already done everything humanly and humanely possible to try to save the patriot’s life.

Casement was not just an Irish patriot but a gay patriot as his diaries left proof that a man could be both gay and a hero.

Maybe you’re wondering what Quinn’s feelings were about Casement’s evident homosexuality, once discovered. JQ did feel that homosexuality was a form of degeneracy.

I wish, instead of mentioning the pseudo-scholar Ezra Pound P Quinn had chosen too highlight the true scholar Lady Gregory as JQ’s dear friend. Her letter to JQ praising his published tribute to Casement is truly beautiful. See Pulitzer Prize winning “The Man from New York” by B. L. Reid if you have not already done so.

Whose handwriting and what did it refer to? Reid does not say because he does not know since he has never seen the “handwriting”. Nor has anyone else.

It is clear you have not studied the question in any depth but have been deceived by the systematic misinformation and calculated confusion published by Reid, Inglis, Sawyer and Others. You will not be aware that in 1959, the UK Home Office confirmed that it had no evidence of anyone seeing the bound-volume diaries in 1916. There is no record anywhere; only police typescripts were shown and a few photos of those typescripts.

If you seriously wish to dis-cover the Casement story, you should study carefully the research on http://www.decoding-casement.com

Well, maybe one of these days. Not particularly interested in Mr. Casement at the mo. Remember, tho, a man is not judged by what he does in the bedroom or the kitchen. Cordially,

P