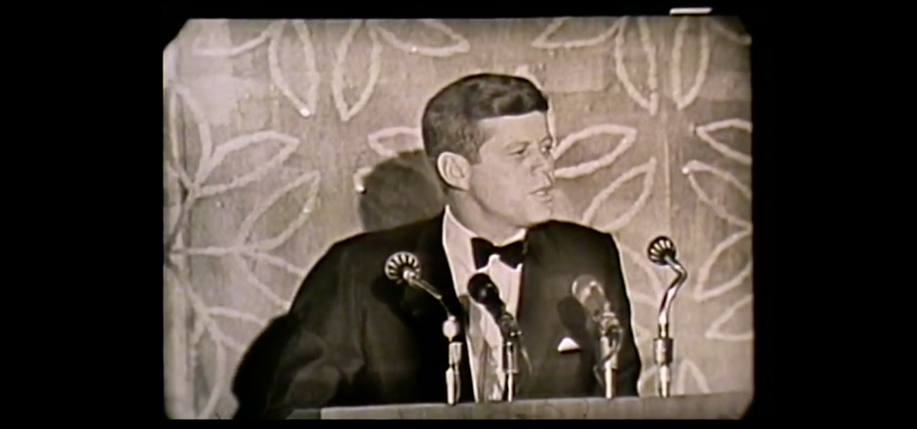

“Immigration policy should be generous; it should be fair; it should be flexible. With such a policy we can turn to the world, and to our own past, with clean hands and a clear conscience.”

– John F. Kennedy

This past Thanksgiving, as I made my way to a friend’s for a home-cooked meal, I thought about my early years in New York when I worked most holidays at my waitressing job. The recent election – and all the trash talk about immigrants, has made me hyper-aware of immigrants I encounter every day in New York city. I love getting my coffee from the man from Afghanistan on the street corner outside my office. We always exchange pleasantries – during the world cup we talked about Soccer and I realized that all those years, he had thought I was German!

It strikes me on this Thanksgiving that most of the workers out there in the city, cab drivers, deli and restaurant workers, are immigrants.

On my way to my dinner, I stop at Welcome Wine & Liquor, as I picked up my favorite Californian pinot noir from the Russian River (the grapes picked by Mexican migrant workers), I chatted to the Indian owner about what we have in common – a history of British colonialism and national flags that have the same colors.

At Godiva Chocolates, one of the shop assistants was from Ghana, the other from the Dominican Republic. At the mention of the Dominican Republic my mind flashed back to a long-ago St. Patrick’s Day and my favorite chef, Roberto.

All the firemen used to line up outside the restaurant on West 44th Street, and trying to get to regular customers on at the tables was a nightmare. Balancing a full martini glass on a tray over my head, I tried to get by a stocky fireman who seemed deaf to my “excuse mes.” In frustration, I gave him a little kick in the leg to get his attention. He yelped like a baby and cried out to all and sundry, “She kicked me.”

Danny, the owner’s son who was bar-tending, called me a donkey and I fled to the kitchen on the verge of tears. Roberto, left his burgers on the grill to pour me a glass of cooking wine. “It’s okay, Flaco,” he said gently. And it was. I threw back the cooking wine and went back out there.

I’m no longer the skinny girl who earned the nickname “Flaco” from my Spanish-speaking workmates, but I fondly remember the short order cooks, the busboys, the cleaners, the waiters (particularly Bruno from Brazil!), that I met over the 12 years it took me to get my papers. We were all from somewhere else, and that was our bond. We were all happy to be in America. No matter how hard the work and long the hours, we lived in hope of getting our papers and in the meantime we did what we could to get by and we enjoyed ourselves, too.

I immigrated in 1972, in the first wave of immigrants from Ireland who were affected by the 1965 Immigration Act, which pretty much closed the door on immigration from Ireland. It was a severe blow. Everyone in Ireland had relatives in America. We always looked this way across the ocean, and not to Europe. Ions ago, our small island was part of the landmass of the northwestern coast of America, so subliminally, there’s a connection.

I didn’t intend to overstay my visa. I worked in Atlantic City for the summer. I met kids from all over Ireland, and I learned more about my own country, and the difference between growing up on a farm in Tipperary, and a village in rural Mayo where the met worked in Scotland picking potatoes. And with three girls from Cork, I spent three months traveling up and down and over and back across the states from September to November, and I learned about Irish America. I loved it.

I loved that so many people I met wanted to know about Ireland – and told me stories about where their people were from. That they had such good will about the place where I was born. I came to see it through their eyes, and came to understand the what it was like for earlier Irish immigrants – place-names gave clues to their stories — I started looking for signs wherever we traveled, some of them stood out like Irish Bayou in New Orleans. Looking for signs is something I still something that I do. I would love to know how Kenmare Street in New York’s Chinatown came to be. Who was that from that small town in Kerry was behind this name?

The cab driver who stopped and picked me up after my wonderful Thanksgiving dinner – the host was from Yorkshire, one of the guest was French, and another had been adopted from China as an infant – was from Senegal. We chatted about his name, Mor, which I told him in Irish means “big,” as in “big heart.” He laughed and said that he had a passenger earlier who told him that in Turkish, mor means “purple.”

In my vision of America, the rainbow has a purple hue. It’s the color you get when you mix red and blue.

Mórtas Cine.

Note: President John F. Kennedy believed passionately that what gave America its “flavor” and “character” was “the interaction of disparate cultures.” He wrote about this in an essay called “A Nation of Immigrants,” which was published as a book in the run-up to the 1960 election. It has recently been republished by the Anti-Defamation League.

_______________

For information on the Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform visit: irishlobbyusa.org.

Were they coming in with dynamite back in the day when you were a waitress? Were they during Pres Kennedy’s days? Dynamite talks. Such rudeness must be curbed.

All you come up with attacks a nerve with me, thanks for challenging your readers.

This is really great work.Thank you for sharing such a useful information.