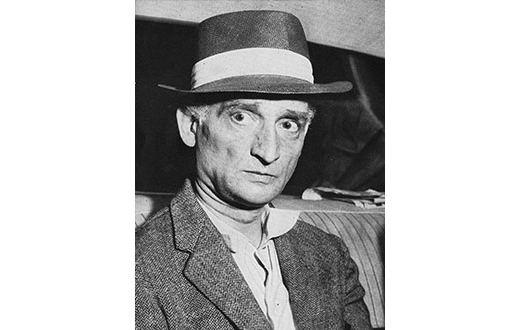

The Irish American New York lawyer who defended a Russian spy, and negotiated on behalf of the thousands of prisoners captured after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, is remembered by his daughter Jan.

It can often appear that the lives of individuals depicted on the silver screen are too fantastic to be real. For James B. Donovan, an Irish-American lawyer from New York who was recently played by award-winning actor Tom Hanks in the film Bridge of Spies, the opposite was in fact the case.

His life was ultimately so seemingly fantastic that it would simply be impossible to depict in a single film. Nonetheless, the 2015 film Bridge of Spies, directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Matt Charman and brothers Ethan and Joel Coen, has succeeded in depicting at least one epoch in the fascinating and inspiring life that Donovan led. The film – which took in $165 million at the box office, and racked up Golden Globe and Oscar nominations and wins earlier this year – is finally helping to get Donovan the recognition he deserves.

“History hadn’t been kind to him,” says Donovan’s daughter, Jan Donovan Amorosi, the eldest of Donovan’s four children. Of her father’s role in many key events of the twentieth century, she felt until recently, “there was nothing much said. It was like he was a forgotten man.”

Nevertheless, the interest now being paid to his life is largely a recent phenomenon – which is a curious fact, considering he played a crucial role in the principal Nuremberg trial at the end of WWII, was the primary negotiator in the exchange of captured agents (the focus of Bridge of Spies), and was personally charged by President Kennedy to negotiate the release of thousands of prisoners following the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. The acknowledgement that Donovan’s many selfless, heroic deeds are now receiving is a relief to his family as well, as Amorosi explains.

“Thank God now everyone knows what an outstanding man he was,” says Amorosi, who remembers saying to her husband, “I don’t understand this. I mean, he did so much for our country and nobody remembers him!”

Donovan was born in the Bronx in 1916, the son of Harriet O’Connor, a piano teacher, and John J. Donovan, a surgeon. Brought up Catholic, Donovan studied first at Fordham, a Jesuit University, graduating with a degree in English. He then studied at Harvard Law School, and shortly after graduating in 1940, married his Brooklyn sweetheart, Mary McKenna, in 1941. A relatively quiet life at a New York law firm followed, but didn’t last long. After the United States entered World War II, Donovan became a U.S. Naval Reserve officer and served as general counsel to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA, which eventually led to Donovan’s crucial role in the principal Nuremberg trials.

“Nuremberg as a young man was pretty horrifying for him,” Amorosi said. “He was pretty upset. Spielberg, however, was very impressed with this aspect of my father’s life because he is a Jewish man and he was so appreciative of my father. He told me, ‘Your father was extraordinary.’”

Donovan became an assistant to Justice Robert H. Jackson, the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, from 1945 to 1949. In his capacity as a lawyer who needed to show the extent of what the Nazis had done, he collaborated with several directors in order to produce some rather harrowing documentaries which would serve as video evidence for the trials. Donovan oversaw the progress of the films and provided legal advice while working with film directors Budd Schulberg, Ray Kellogg, and George Stevens – all of whom were working for the OSS at the time.

“There were famous Hollywood directors, for example, George Stevens, and they all gave their talents to the war effort. So my father met them over there, in Europe during the war,” Amorosi explained. Through these connections, films like Nazi Concentration Camps and The Nazi Plan were produced and used as part of the evidence against the Nazis.

Amorosi says that Spielberg watched these same films, and even showed them to his 96-year-old father. “They could not believe it,” says Amorosi, adding that Spielberg told her that her father was truly unbelievable. “Spielberg of course couldn’t be more grateful,” she said.

As for the family’s first-hand experience with the director, Amorosi was extremely impressed.

“Steven Spielberg could not have been nicer to us. He’s such a kind and lovely person. You don’t know what to expect when you meet someone really important like that. We came away so impressed with him.”

Outside of garnering interest in her father’s story, Amorosi found the film making process personally rewarding as well. Since the film had scenes showing the whole Donovan family, Amorosi was depicted as a character in the film, and was played by Eve Hewson (who just happens to be the daughter of Bono, the front man of the legendary Irish rock band U2).

“In the film, I’m the girl who dives under the table because supposedly there was a gun that was fired into the house. That did not actually happen,” she explained, but was nonetheless pleased with Hewson’s performance and with meeting her in real life.

“That girl is really adorable,” says Amorosi, “She is lovely. She lives in Brooklyn and we hung out for a while at a party. We were sort of leading the Hollywood lifestyle there for a while when the movie came out.”

But Bridge of Spies hardly touches on Donovan’s role at Nuremberg. Its main focus, rather, starts around 1957, when the New York City Bar Association asked Donovan to step up to defend Rudolph Abel, a Soviet spy who’d been captured and charged as a Soviet agent by the FBI and the INS in Brooklyn. Despite the fact that many other prominent New York lawyers had been approached and refused, Donovan took on the case. At the time, he said it was an important responsibility that gave him “the privilege of advocating unpopular causes.”

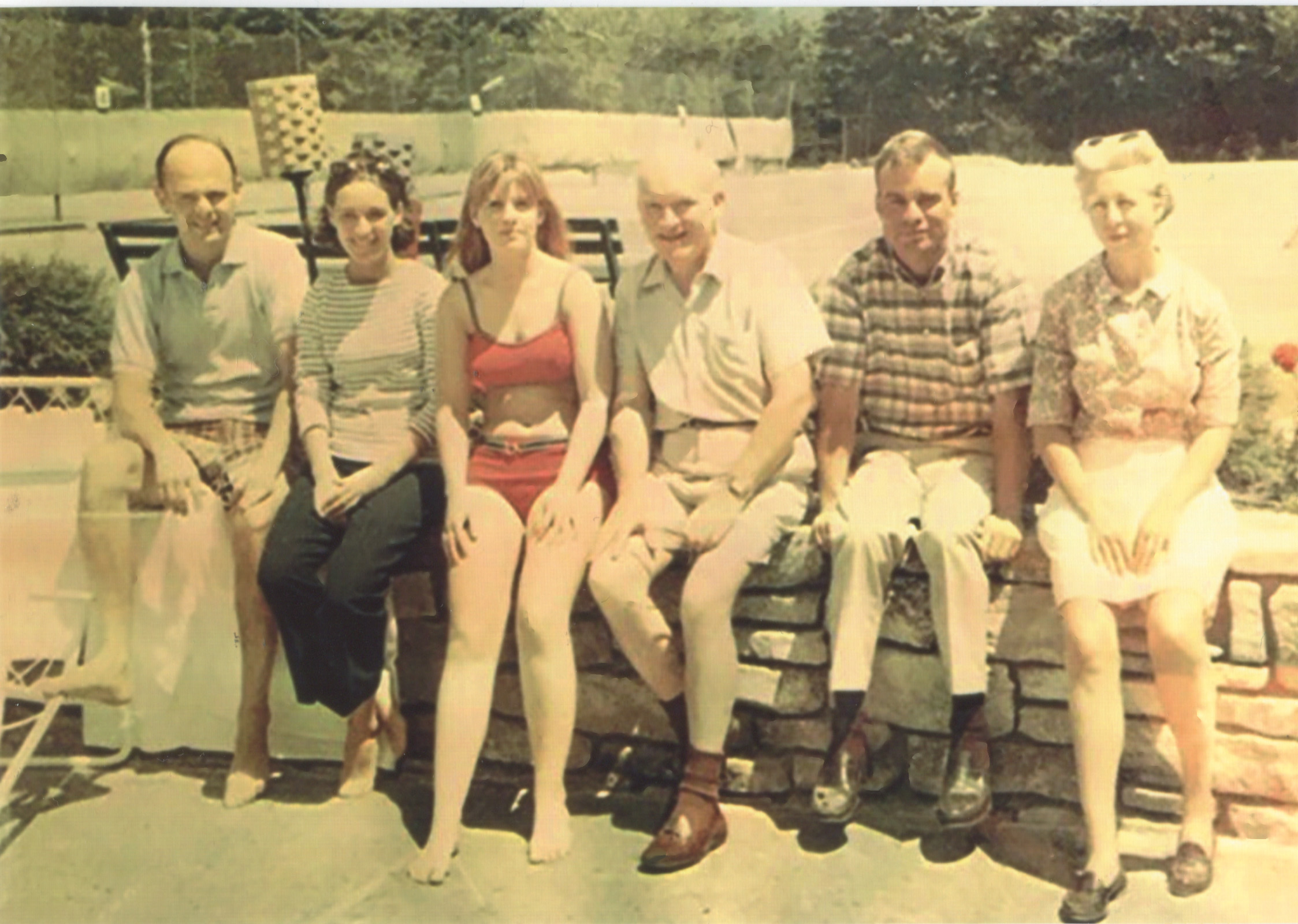

Amorosi was present when her father made the fateful decision to defend Abel. She remembered that at that time her younger siblings were off at camp, so it was just her mother, her father, and herself at the cottage they were renting in the Adirondack mountains.

“The phone rings and it is one of my father’s associates from the law firm saying, ‘they captured a Russian spy in downtown Brooklyn.’ Some of the other lawyers had convened a meeting and they had decided that because of my father’s background, in particular, the Nuremberg trials, that my father would be a very good choice to defend this Russian spy,” she says.

“As you see in the movie, my father was at first startled. He said to us, ‘What do you think I should do?’ And we both said, ‘You should do what you feel you want to do.’

“He said, ‘I’m going to go out for a while and I’m going to think about this.’”

Amarosi thought then that he would be pondering this momentous decision for days or even weeks – it was an onerous and dangerous decision for him and his family indeed, since Abel was sure to be depicted as persona non grata in the media, and Donovan would be seen as his defender.

“But instead, he came back within a couple of hours,” Amorosi says. “We had just arrived – we were unpacking our things for our vacation and he came back to the house and said, ‘Well. I’ve made up my mind. I’m going to do it!’

“He made quick decisions, and he loved challenges in his life. So every challenge he could face, he faced. And I think this may have come from Nuremberg, where as a very young man he had to face the Nazis and witness things that were horrifying. He was in charge of the visual evidence at 32 years old. How many young men would do something like that? He welcomed the challenge.”

During Abel’s trial Donovan was up against a difficult test since the local New York population, the media, and all the government agencies involved in the case had already made up their minds that Abel, who had spent nine years undetected in the U.S. posing as a painter – his studio across the street from the local FBI office – was guilty.

Though Donovan lost what became known as the “Hollow Nickel Case,” and the U.S. Federal Court in New York convicted Abel on three counts of conspiracy as an enemy agent, the resourceful lawyer managed to persuade the court not to impose the death penalty.

“The death penalty would end all possibilities of Abel helping us,” he explained at the time. “Some day in the future an American of similar rank may be held by the Russians and an exchange can be worked out.”

Such thoughts came naturally to an insurance lawyer like Donovan, who spent a great deal of time thinking about hedging one’s bets.

While most lawyers would have called it a day when Abel was carted off to serve 30 years in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, and a return to a steady and lucrative corporate practice would have been the smart play for a lawyer with a young family, Donovan continued to litigate on the spy’s behalf. He argued that evidence used against Abel was tainted, since the FBI had seized it in violation of the Fourth Amendment. When he took Abel’s case all the way to the Supreme Court he only lost by one vote – Abel v. United States was rejected in 1960 in a five to four decision, with the dissent led by Justice William Brennan, and Justice William O. Douglas Despite losing the case, Donovan was satisfied he had pursued it to the full extent of U.S. law and that Abel had been given a fair hearing. “The very fact that Abel has been receiving due process of law in the United States is far more significant, both here and behind the Iron Curtain, than the particular outcome of the case,” he said at the time.

Amorosi recalled that the family was very proud of him throughout the whole process. “Because let’s face it,” she says, “he was probably the only person to say that he would do it. Someone had to do it – and he did a great job. Everything he did was to the best of his ability. He was very dedicated, and very brave about everything. He was incredible. He just made up his mind, and whatever he did was so well done. I don’t know what to say except that we’re so proud of that.”

Arguing to keep Abel alive turned out to be an incredibly prescient move on Donovan’s part when, three years after his trial, a top secret U.S. spy plane – the U-2 – was shot down while taking surveillance photographs of Soviet military installations from 70,000 feet. The pilot, Francis Gary Powers, was captured and tried in Moscow as an enemy agent, and sentenced to three years imprisonment and seven years in a labor camp. Powers was in prison from September 9, 1960 until February 8, 1962 when the CIA opted to use Abel as a bargaining chip. Unsurprisingly, they turned to Donovan to negotiate a prisoner swap. Donovan led a mission to East Berlin, and following a week of negotiations at the Soviet embassy there, successfully negotiated for the exchange of Powers, as well as an American student, Frederic Pryor, for Abel.

For Amorosi, and the rest of the Donovan family, Bridge of Spies is a well-deserved salute to their father’s bravery and doggedness through this episode of his life. The film, incidentally, came out one hundred years after his birth.

“For us it was an exciting movie – and it continues to be exciting – because, before this, people had forgotten him,” Amorosi says. “But now our father’s role has finally been recognized. And while this is something that should have been done quite a while ago, thank God it’s been done now! And we’re very, very thrilled.”

She’s happy, too, that as well as being celebrated in the movie, Donovan’s account of the inspiring tale in his own memoir of these events, Strangers on a Bridge: The Case of Colonel Abel and Francis Gary Powers, which was first published in 1964 – and was widely acclaimed at the time – has been re-released by Simon & Schuster.

But just when the dust began to settle after Abel, Powers, Pryor, and Donovan were back in their respective countries, Donovan’s life took another interesting turn. Again, it began with another surprise call – but this time to the Donovan home in Brooklyn.

When the phone rang, Amorosi recalled that her father was sitting at his desk in his wood paneled den that featured, upon his insistence, a ceiling painted blue.

“He liked a blue ceiling in a room because he found it very peaceful,” she said. But when that phone rang it was not peace and quiet that was on the other end, but rather, a new special mission request – this time being made by the President of the United States.

“A call comes from President Kennedy,” Amorosi says with the nonchalance that could only come from a person who grew up with a father of larger-than-life design. “And so he took the call.”

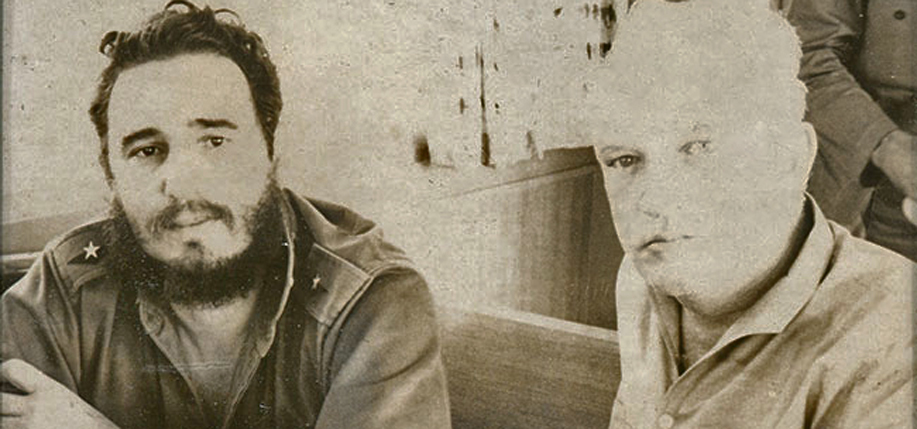

Because of his success at Nuremberg and his dealings with the Soviets, the president wanted to know if Donovan would be willing to negotiate on behalf of prisoners captured after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba on April 17. 1961, funded in part by the U.S. government. Despite the escalating tensions between the U.S. and Cuba, Donovan agreed to take on the job, and according to Amorosi, shuttled back and forth to negotiate with Fidel Castro no fewer than 15 times.

Here too, Donovan proved highly effective in his negotiations and secured the release of over a thousand prisoners to the U.S. Part of this was done through earning Castro’s trust and respect, which was achieved in no small part by Donovan’s decision to bring his son John down to Cuba with him. “What was behind it is that he felt that Castro would admire him for taking the risk in bringing his son along,” says Amorosi. “My brother was really only a very young boy at that time.”

The gambit paid off, and Donovan himself recalled: “Castro was enormously pleased to meet John and was completely taken by my self-confidence in bringing him.”

Throughout the negotiations the two men developed a rapport and a great deal of mutual respect, and on December 21, 1962, they signed an agreement to exchange the 1,113 prisoners that had survived the invasion in exchange for $53 million – what today would be $410 million – in food and medicine. Apparently Donovan came up with the idea to exchange the prisoners for medicine after he suffered an attack of bursitis and found the Cubans had nothing available with which to treat it.

On top of that, and just as he had upped the ante in getting Pryor released from East Germany along with Powers, in the instance of his high-profile negotiations in Cuba at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, he nevertheless managed to negotiate for the freedom of an additional 8,500-odd political prisoners from Cuban detention.

Meanwhile, certain forces in the CIA also attempted to get Donovan to assassinate Castro by gifting him a wetsuit laced with poison. Just as was the case during the spy exchange in Germany, Donovan refused to be a pawn in the CIA’s game.

“[The CIA] wanted my father to kill him,” Amorosi ruefully recalled. “They wanted my father to put a poison dart in Castro’s wetsuit. But my father, since he was in the OSS, had a feeling that something would be amiss – that they were going to try to pull something. So he thought, you know, I’m not going to be part of this. So he went and bought a different wetsuit in New York and brought it with him to give to Castro.”

Despite all of that, Donovan still managed to make friends with the locals while in Cuba. “Every place he went he made friends,” remembers Amorosi, “He got to know some local Cuban people and became friendly with all these people.” Many of these relationships, she maintains, lasted for years after the fact – a testament to the sort of kindness, humanity, and integrity that her father embodied throughout his life.

Amidst all the stories of adventure and intrigue, Amorosi insists nonetheless that it’s the seemingly banal incidents in her father’s life that have taken on a special significance for her since his death of a heart attack, his third, at the age of 53, on January 19, 1970, at New York’s Methodist Hospital.

“My father was a fantastically interesting person,” she admitted. “He had a lot of enthusiasm for life, and because he was such a lively person, we all reveled in that.”

In particular, she remembers he loved family holidays together, celebratory meals, and especially Christmas Day.

“He had a favorite bathrobe that he wore every Christmas,” she remembers with a smile in her voice.

“It was so funny,” she adds. “I was speaking to my brother this year on Christmas day and I said, ‘Remember that red plaid bathrobe that daddy had and always wore on Christmas?’ And he said, ‘Guess what. I’m wearing it right now!’ We have truly fabulous memories.” ♦

Why not put him in for sainthood?

Because some saints will be ashamed. He was a true saint. God sent.

what a great man. rip James Donovan

Thank you for this lovely story. Was James Donovan related to William Donovan who was part of getting the CIA started?

best wishes,

Ron

No family relation but Wm Donovan took on my father, James Donovan, as his general counsel at OSS.

My father worked at Watters and Donovan.

Brilliant film and fascinating man, should not be forgotten but go down in history as one of the US’s more prominent and important men.

I saw the film first, then read Bridge of Spies. But the REAL story is James Donovan’s book, Strangers on a Bridge. I just returned from Berlin, where I walked across the Glienicke Bridge. I had lived in West Germany during the Cold War, and it was with great interest that I read about this story long before the film came out. Great man. James Donovan IS a Saint!

My father, Henry Bourke Weigel and his brother, George K.Weigel, sons of an Irish immigrant mother, Ellen Bourke Weigel, both appeared to know Jim Donovan relatively well. Both went to Cornell University; my father in architecture and his brother in finance. Both had professional lives in NYC. So where would they have met and associated with Jim Donovan? They both spent summers in the Adirondack Mts. at a family camp about an hour away from Lake Placid. We all went over to Lake Placid once when he invited us to dinner at the Lake Placid Club. Was this the same Jim Donovan? Always curious about the association.

Such a wonderful legacy – and you can hear the one in his daughters ‘voice’ which means his legacy shone brightest with those most important—his family!

Did lawyer James Donovan and Rudolf ever meet after the war and the fall of the wall?

I too served in Berlin during the Cold War….before, during and after the wall. Our home was in US military housing not far from the Glienicke Bruecke. I am always attracted to anything associated to Berlin ever since the late 80’s-very early 90’s & this man’s & his family’s incredible story & experiences just goes so far beyond an average story. I can only imagine the difficulty (to say the very least) that being in that position (defending a despised/ unpopular individual in our midst) in those years must’ve been like. It was that way for me in the early 60’s as Mr. Donovan’s young son was depicted. I recall the deep, true social core angst fearing the Soviets were destined to drop something out of space onto the US & all of us at any moment. I remember the duck & cover training in elementary school, the Civil Defense (CD) school assemblies & how our astronauts, pilots and military were so deeply revered as the nation’s tip of the spear defenders, warriors & saviors (little “s”). And here we now finally hear of James Donovan’s tremendous efforts, courage & contributions on our behalf from an unaddressed – hidden direction. Well done all…for living this, recording this and bestowing the legacy for us all to recognize & honor.

Today August 7, 2022, saw for the first time the movie about James Donovan, an excellent story about the life of this great man.

I have lived in this country for over 60 years, I am originally from Cuba, and I remember when the negotiations to release the Cuban prisoners took place when I was around 21 years old. and living in New York.

As Cuban, I am very grateful to Mr. Donovan to care about many of my people.

Thank you, Mr. Donovan RIP

.

This is an amazing story. Of course I saw and loved Bridge of Spies, being a fan of all things spy-dom and our history of it (and in it!) -when Donavan asks Abel if he isn’t afraid and Abel replies “Would it help?”

Thanks for a great profile! He was a man of courage and ethics. Rare today ! Thanks Irish American for publishing this amazing piece-

I’m always fascinated to learn things I didn’t know; especially during the Cold War. I’m glad that James Donovan’s life and heroic efforts were brought to life in this film. The fact that he wasn’t going to let Pryor rot in a German prison for something he didn’t do is just beyond words. May his soul rest from all his efforts of humanitarianism. Unfortunately the cia is still up to the same old tricks but has bumped it up a notch in this day we’re living in.

I was born in Heidelberg in 1960 so i was there while this was going on my American father was a vet of ww2 and a federal employee my mother was German. We came to the us in the summer of 63 by way of Brooklyn navy yard. This movie brings back my memories of my parents as they brought me to Colorado as little boy

Brave patriot for the USA wish we had more like him today we sure need people with his faith in the USA

I LOVE HISTORY! How I didn’t know this is unbelievable! Just watched the movie Bridge of Spies then internet searching began ..HOW VERY PROUD I AM OF MR POWERS AND MR DONOVAN! AMERICAN HEROES! IM 67yrs old and very sadden I didn’t know this history before now. IT MAKES ME EVEN PROUDER TO BE A AMERICAN CITIZEN!GOD BLESS AMERICA AND THESE TWO HEROES!