Nora Brosnan’s role in the fight for Irish independence is remembered by her granddaughter.

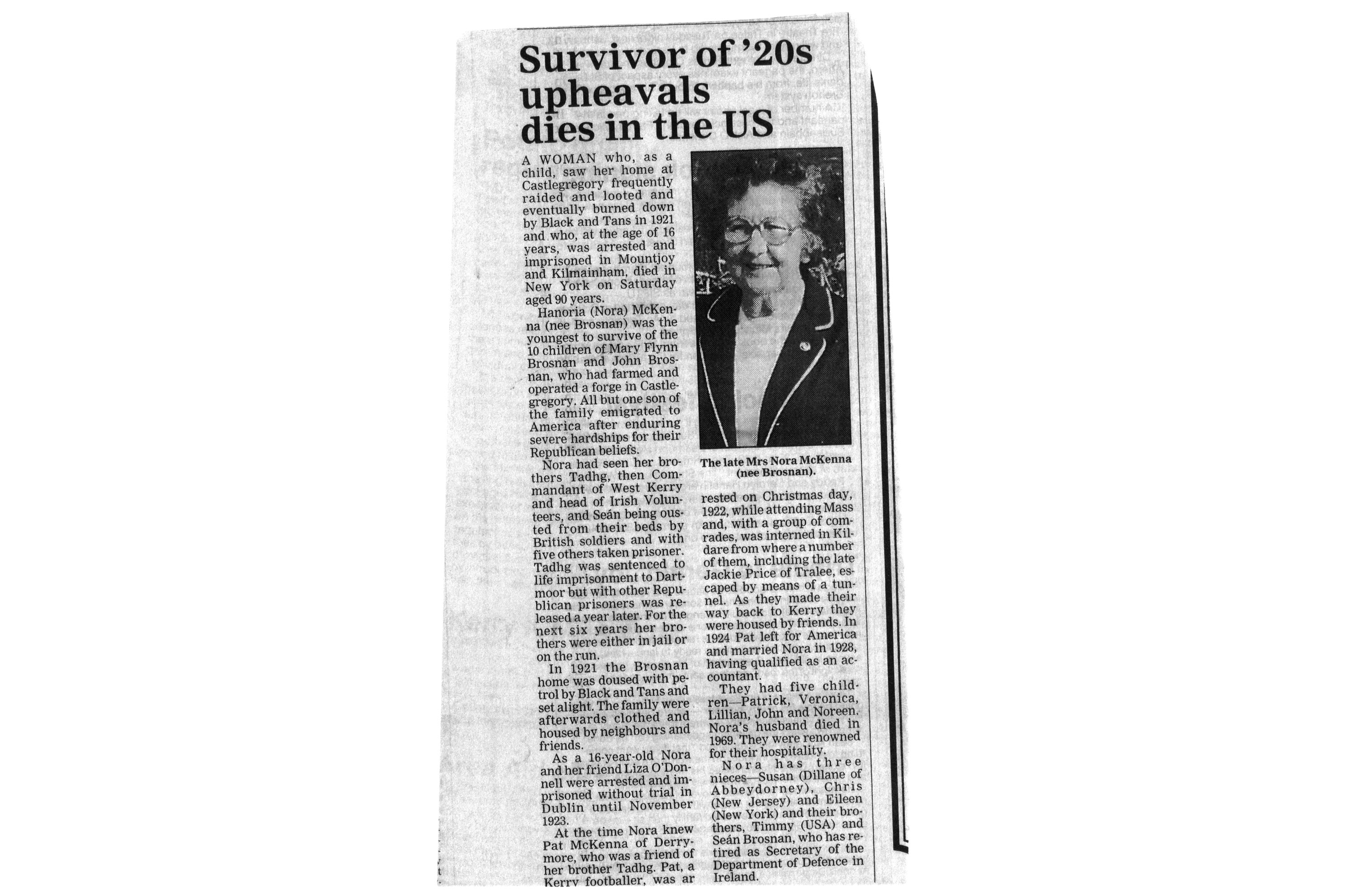

Hanora “Nora” Brosnan was born on September 17, 1905, the youngest of 10 children, to Mary Flynn Brosnan and John Brosnan, in Castlegregory, County Kerry. Nora’s father was a farmer and the owner and operator of a successful local forge.

The Brosnan home was a comfortable place with a large kitchen where the family would gather, and a loft bedroom over the kitchen that Nora shared with her sister Lil. Every family member had chores, and Nora was no exception. When she was just eight or nine years old, she was responsible for controlling the cat population. Her job was to take the kittens, put them in a bag and drown them. At the time, it was just part of life on the farm, never striking her as an odd or unpleasant task. She was also taught to kill and clean the chickens and ducks for family dinners.

War with England

The daily routine of farm life was cut short by the Easter Rebellion on April 24, 1916. On May 1, Nora’s brothers Tadg and Sean were ousted from their beds and arrested for plotting to attack the British Army headquarters in Tralee. As commandant of the West Kerry Irish Volunteers, Tadg accepted responsibility. The six others involved were set free. Tadg was sentenced to life in prison, later commuted to 20 years. Fortunately, after serving one year in Dartmoor Prison in England, he was released following the armistice of 1917.

Around this time, three of Nora’s brothers, Mike, Jim, and Maurice, immigrated to America. Sean and Tadg stayed at home and remained active in the IRA, the successor to the Volunteers. For the next six years, Nora saw them only when they managed to sneak home for a quick visit.

The effect of the war on the family was hard; the forge all but closed and the soldiers made frequent raids on the Brosnan home – sometimes more than twice in one week. Nora’s father was often arrested simply because the soldiers were frustrated in their attempts to apprehend Tadg and Sean. It was during this time that Nora also began actively aiding the IRA cause, making bundles of clean socks and shirts and taking them to the rebels on the run.

One November night in 1920, the British Army irregulars known as the Black and Tans (for the uniforms they wore), made one of their usual raids at the Brosnan home. Nora’s memories of the night, passed down through the generations, was that the family was relieved to have the raid over early. By 9:00 p.m., they were in bed. But during the night they were awoken. The soldiers had burglarized the local pub and were drunk. They kicked in the front door and announced to the Brosnans that they were there to burn their house down. They stole the family’s valuables and fine china, and what they couldn’t carry, they smashed. Nora’s prized possession was a doll her brother Mike had sent from America. One of the soldiers, taking the butt of his rifle, smashed the doll’s porcelain face in front of Nora before throwing her out of the house.

In the yard, Nora saw her mother wearing only a nightgown. She fought her way through the soldiers, who were busy dousing the house with gasoline, and made her way to her parents’ room to get her mother a pair of shoes and a shawl. After the soldiers had stolen all of the valuables and doused the feather beds with gasoline, they lit the house on fire.

Good friends and neighbors gave the family shelter. In the weeks following the fire, Nora’s parents returned to the house to try to repair what they could until the house was habitable again. Even after they were able to move back into the house, life was not the same. The windows, which had shattered in the fire, were now boarded up, and all but a few pieces of furniture had been destroyed. Nora and Lil had managed to save only the dresser and a pitcher and bowl from their bedroom.

The Civil War and Nora’s Arrest

In December 1921, following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty that divided Ireland into what would become the Free State and the six northern counties, the Brosnans, like many Kerry families, rejected partition and began supporting the anti-treaty forces.

One November morning in 1922, Nora, who was then 17 years old, was having breakfast with her brother Sean. Someone came to the house to tell them that the pro-treaty forces known as the Free State Army were landing in Tralee Bay. Sean told Nora to go up to the “station,” which was the headquarters for the IRA, to alert them to what was happening. Nora took her friend Liza O’Donnell, and the two were on their way back home from the station when they decided to move the explosives that the IRA had hidden in the village so “the staters” wouldn’t get them. But as they were crossing the station grounds, they were spotted by soldiers who fired shots to halt them. They ordered the girls to “advance forward.” Nora refused to budge, and shouted, “If you want us, here we are!”

Nora and Liza were captured and taken to the local school house where they stayed until nightfall. Then they were taken to the Helga, a ship anchored in the bay that served as a temporary prison. As the soldiers marched Nora past her home, she refused to go any further until they allowed her to see her mother. After some discussion with the stubborn young woman, the soldiers agreed. Mary and John were sitting by the fire. “Glory be, what are you doing with these two little girls?” Nora’s mother asked.

Nora told her parents to stay calm, took her coat from her room and continued with the soldiers to the ship.

The ship’s captain was a kind Englishman who was shocked to see two young girls on his boat, which was not equipped to hold prisoners. He gave Nora and Liza his “day room” until arrangements could be made.

Two days later they docked. They were taken by armored car to Tralee Jail. The girls stayed in Tralee for two weeks with 21 other girls who had also been arrested. Then they were then placed on a cattle boat, which Nora recalled as “a filthy, lice-infected, smelly old wreck,” and sent to Mountjoy Prison in Dublin where they were incarcerated without trial.

The girls were billeted in a room with dozens of other female prisoners. They were given a bed and food rations. However, the beds were taken away as punishment following an escape attempt by two other girls.

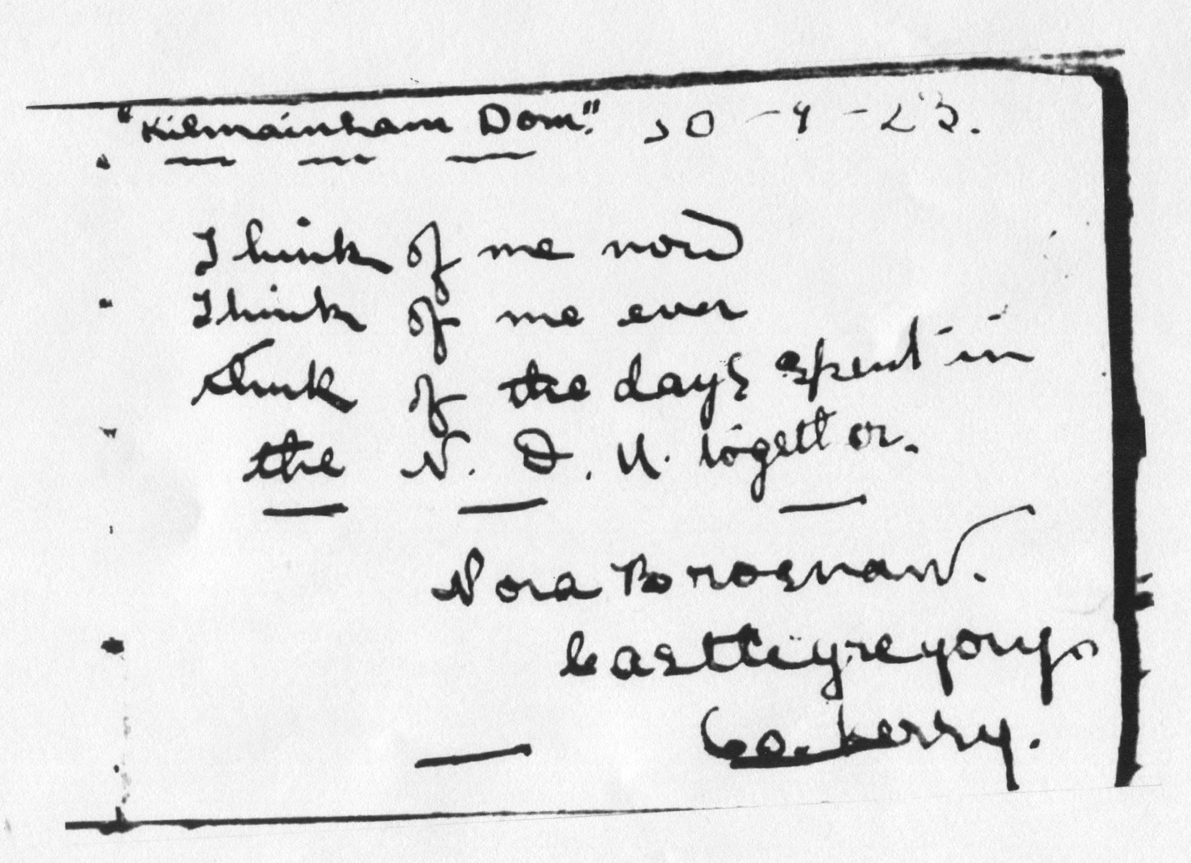

In February, 1923, Nora and Liza were transferred to Kilmainham Gaol where Nora shared a cell with Grace Gifford Plunkett. Six years earlier, Grace had married Joseph Mary Plunkett, one of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, in the chapel at Kilmainham. The morning after their marriage, Plunkett was executed.

At 90, Nora’s memories of her time in prison were still vivid. In 1995, she told Patrick J. O’Leary, a reporter for a local newspaper: “I can still see that awful exercise yard where the sun never shone over the 40-foot walls. I often walked with Grace in that yard. She worried about me because I was the youngest of the female prisoners. She was a very beautiful, very talented but a very private person. She painted a beautiful mural of the Blessed Mother on the white-washed wall of the cell. ”

One Saturday, a year after their arrest, Nora and Liza were released with no money, directions, or means of contacting their families. Pauline Hassett, a friend and a fellow prisoner, managed to slip a piece of paper to Nora as she was leaving. On it, she had written the address of her brother Roland “Rollie” Hassett, who lived in Dublin. The girls were able to find Rollie, with the help of some friendly Dubliners. He bought them dinner on Sunday and put them on the train home to Kerry on Monday morning.

Castlegregory was a very different place when Nora returned home in November 1923. The forge was all but closed and the family was poor. All of the young people were leaving or had already left for America. It was not long before Nora began to think of going, but it would be another three years before she made the trip.

Tadg, Lil, and Tadg’s friend Patrick McKenna left for New York in 1924, and Nora moved to England to train as a nurse.

Patrick McKenna had been very active in the fight for Irish freedom. Arrested and imprisoned in 1922, he escaped, and made his way back to Kerry a year later. His daring sparked Nora’s interest, and the two stayed in touch after he moved to the U.S.

As Nora would later tell it, she worried that Pat was having too much fun in America without her, so she made the decision to join him and her family in New York. Pat sent her the money for the fare.

The United States

Nora arrived to New York on March 17, 1926. She went to a dance with Pat that night and the two began going steady. Pat had become an accountant and had a good job at Pan American Oil Co. Nora soon found work as an assistant nurse at the Hospital for Joint Diseases in Manhattan, earning the grand sum of $60 a month.

Nora and Pat were married on April 28, 1928, at St. Joseph’s Church on 125th Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. They eventually settled in Hartford, Connecticut where they lived for 16 years, before moving to Queens Village, New York.

A rebel to the end, Nora, told the reporter O’Leary in 1995: “We got the British out of Ireland in 1922, but we were left with six counties in the north. We must get the British out of that area.” Asked if she was ever afraid, she replied: “Never! I knew the good Lord and the Blessed Mother would see to it that I was taken care of.”

Nora passed away on January 12, 1996, but I will always be thankful that I, and my children, had the chance to know her. She passed her love for Ireland, her strong sense of family, and her unique outlook on life down to her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and we still have that connection to Ireland.

Nora’s brother Sean was the only Brosnan to remain in Ireland. He ran the family farm, which is today owned by his son Sean.

On September 16, 2016, Nora’s great-grandson Patrick Wolfgang McKenna was born in Manchester, Connecticut, one day before what would have been her 111th birthday. He will grow up knowing that his great-grandmother was a rebel Irish girl. ♦

_______________

DO YOU HAVE A FAMILY STORY TO TELL? Please send photographs and story to: The Editor, Irish America magazine, 875 Avenue of the Americas, Suite 210, NY, NY 10001. You can submit your story by email to: submit@irishamerica.com.

That’s my great great grandmother ☺️

I MUST CONTINUE THE LEGACY

My great grandad is her son Joseph mckenna which I am named after, it’s so crazy reading all these stories about your own family.