Five years ago this summer, a dream came true – but not quite the way the daydreamer envisioned it might.

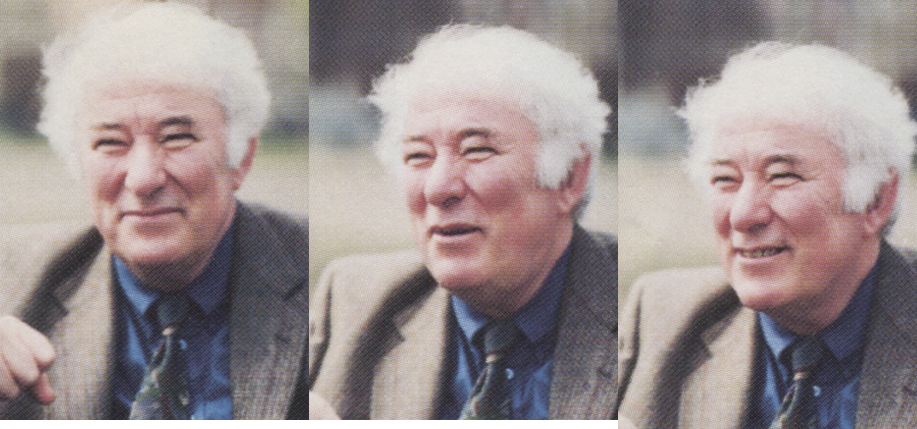

A decade earlier, I approached the poet and Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, proposing a magazine profile of him and requesting an interview in Dublin.

An enthusiastic admirer of his work, I’d just published an assessment of his translation of Beowulf – “a cross-cultural tour de force” reflecting “artistic taxidermy” – and hoped the full-throated hurrah would strengthen the pitch for a meeting.

Not long after I dispatched my letter, an envelope arrived with a handwritten postcard (from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art) tucked inside. “Many thanks for your invitation to do an interview,” the fountain-pen script began. “I apologize for the brevity of this response, but I go off tomorrow for a week and a half, so want to get a reply to you now. I regret that April would not work: I’m lecturing in Tulsa when you’re in Dublin.”

With details of his travel plans matter-of-factly spelled out and conspiring against my sojourn in Ireland, Heaney continued in a completely different (and in its phrasing almost poetic) vein.

“I also regret that I feel a bit interviewed out: I feel as if I’ve spoken every authentic word into some microphone or notebook – time to gather a bit of moss in the mouth.”

Though he concluded with appreciation for my “good disposition” towards Beowulf, Heaney’s remark about being “interviewed out” was revealing. Was the poet, who kept turning so many moments of his life into verse that will surely stand time’s test, suggesting that a retreat from pesky prose scribblers would be his post-Nobel Prize preference?

In Heaney’s thinking – or so I concluded – using personal experience and maintaining some semblance of privacy weren’t activities in conflict. I’d let him “gather a bit of moss in the mouth” and not bother him again about an interview.

That decision, though, didn’t mean my own fascination with Heaney and his poetry flagged. By chance, I happened to be in Dublin doing research for a book during the spring of 2009, when “Famous Seamus” (his Irish nickname) turned 70 years old. It was a national celebration, complete with a boxed set of CDs of him reading his Collected Poems (11 books worth), television documentaries and the broadcasting of his birthday speech across the island.

One tribute featured more than a dozen poets from several countries, reading favorite Heaney compositions with the poet listening to these other voices recite his words. At this event in a Dún Laoghaire theatre, each attendee received a reverse birthday present: an autographed copy of Heaney’s poem, “In the Attic,” which The New Yorker had just published.

Reaching 70 was not without time’s burdens, especially in terms of remembering for the poet. “As I age and blank on names,” he confesses in one line from “In the Attic,” later observing,

As the memorable bottoms out

Into the irretrievable.

Two years later, I was back in Dublin on a teaching assignment, when I received an invitation to attend University College Dublin’s ceremony for the conferring of honorary degrees and the awarding of the Ulysses Medal, the university’s highest honor. The 2011 recipient was none other than Seamus Heaney.

A luncheon followed the academic formalities. As we were leaving (a half-hour or so after most tables), I noticed Heaney and his wife, Marie, by themselves near the door leading outside. Possibly emboldened by an extra glass of the afternoon’s wine, I did something I never do.

With pulse-racing trepidation, I approached the couple to offer a wayward Yank’s congratulations. As we talked, Heaney claimed that he recalled the long-ago interview request, apologizing that we hadn’t been able to get together.

Did he truly remember my overture among the countless he received with daily regularity? I don’t know, but what he said was kind and the brief exchange well worth the newly discovered courage it took to initiate.

A couple weeks later at the launch of a new book of poetry at O’Connell House, Notre Dame’s center of activities in Dublin, Heaney attended. Seeing each other produced a smile of recognition from him as well as a handshake. An acquaintanceship of sorts was probably better than any interview, I judged.

On August 30, 2013, Heaney died. Word of his passing dominated news throughout the world. The New York Times devoted page-one, three-column, attention to its obituary, which appeared above the fold and included a large picture. His funeral was broadcast on Irish radio and television.

Heaney is buried in his home village of Bellaghy, County Derry. Last August, a simple headstone was placed on his grave, and it featured a seven-word inscription that’s also a command for the ages: “Walk on air against your better judgement.”

In poem after poem, Heaney did just that, taking verbal risks enduring literary art demands. In the process (as he wrote in “Personal Helicon”) he “set the darkness echoing” – and he also, in one case, made a dream come true through his own kindness that continues to echo. ♦

_______________

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair in American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame and the author of Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising (Oxford University Press).

Leave a Reply