ABC’s John Donvan captures the challenges, activism and inspiration of living with autism.

℘℘℘

Robert Foster Kennedy was born in Belfast, where he studied to become a doctor at Queens College. In 1942, Kennedy published a chilling article in the American Journal of Psychiatry. As described by veteran ABC News television correspondent John Donvan in his fascinating new book In a Different Key: The Story of Autism, Kennedy’s article was “a soberly worded endorsement of ‘mercy killing’ for mentally disabled children.”

Kennedy wrote that “nature’s mistakes” deserved relief from the burden of a life “that at no time can produce anything good at all.”

Kennedy’s views were particularly troubling, notes Donvan – an Irish American whose maternal grandmother came to the U.S. from Clare on the famed ship The Lusitania – because “the United States was by then at war with the Nazis.”

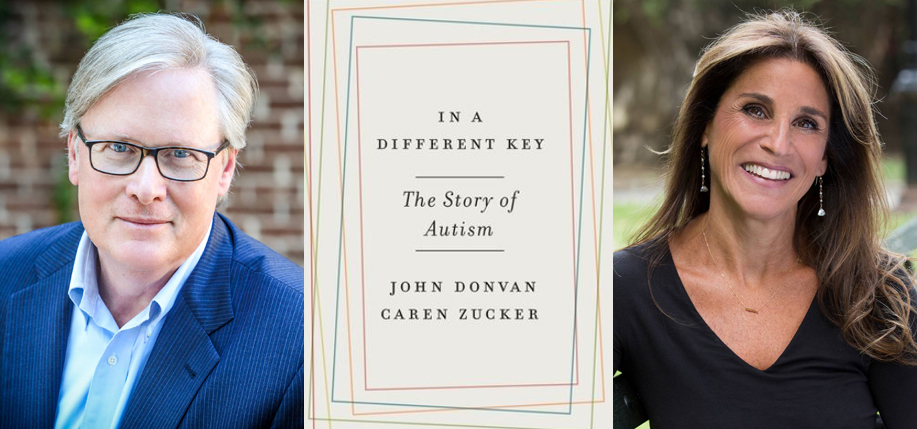

Donvan’s book – co-written with Caren Zucker, his longtime producer at ABC – has garnered widespread praise as perhaps the most authoritative book ever written on autism, the sometimes frightening ways experts have responded to mental illness in general, and the inspiring activism of parents on behalf of their children.

“When I went to school there were no kids with autism because they weren’t allowed,” said Donvan in a recent interview with Irish America magazine.

Interest in autism, of course, has exploded in the past decade or so. Back in March, the Centers for Disease Control released its latest statistics, which found that one in 68 American children were diagnosed with some degree of autism. That’s up from the CDC statistics for 2007, which found that one in 150 children were on the autism spectrum.

The debate over autism’s prevalence is, of course, controversial. Some experts and celebrities have argued that vaccinations have led to the spike in autism. Others have suggested that autism results instead from bad parenting or low expectations when it comes to behavior.

But Donvan and Zucker both know all too well about how autism can affect the families of those living with it. And they have performed a great service by writing In a Different Key, not only because they correct many myths about the disease, but also because they tell the stories of those parents and children who refused to accept their status as second-class citizens who deserved little more than a “mercy killing.”

“We wrote the book because we were trying to inspire people who are inside the autism world, to let them know things have come a long way,” said Donvan, whose Israeli-born wife was profoundly affected by her autistic brother.

“I wanted to understand what her life was like. And the more I talked to her mother about it, the more I started to see there was this untold, turbulent back story.”

Donvan added: “I began to realize that when you have a disability in your home it really changes your home. It’s often been a divider from the rest of the world.”

℘℘℘

Donvan is a lifelong Irish American New Yorker. His father’s family came from Cork around the 1850s, and he says (as far as he knows anyway) that’s when the name was changed from Donovan.

Meanwhile, Donvan’s mother family came to the U.S. in the early 20th century, instilling a strong sense of Irishness in the future journalist.

Being Irish “was a pretty big deal growing up,” Donvan says. “We were one of those families that had a Kennedy picture on the wall.”

Donvan has even paid a number of visits to cousins living in Ireland, as well as a family farm in Clare, located near Shannon Airport.

“My mom had a sense of history, a sense of heritage, a sense of family. She grew up with Irish pride,” Donvan adds, who attended Regis Catholic High School in Manhattan, and then Dartmouth.

Though he comes from a family of police officers and public school teachers, Donvan caught the journalism bug. During a sterling broadcast career, he has hosted the iconic show Nightline and served as chief White House Correspondent, while winning three Emmy Awards.

In 1994, the producer he worked with at ABC, Caren Zucker, had a son, who was diagnosed with autism three years later. This exposed her to the challenges, as well as the activism, of families living with autism.

“She really wanted to tell these stories,” notes Donvan. “I already knew something about autism and she was living it.”

But there were also challenges.

“No one was really [talking about autism] even 16 years ago,” notes Donvan. “It was a hard sell at ABC.”

Eventually, Donvan and Zucker ran several stories on Nightline. They haven’t really stopped telling the story of autism since.

“All of us have a part in this story, whether we know it or not,” he says.

℘℘℘

One of the most disturbing themes in Donvan’s book is just how wrong many experts have been about autism over the years. There were those influenced by the frightening eugenics movement, like Robert Foster Kennedy, who believed that those experiencing mental illness did not deserve to live.

Then there was the famous Austrian-born psychologist Bruno Bettelheim. Renowned to this day, Bettelheim had spent time in a Nazi prison camp. Afterwards, he worked at the University of Chicago’s Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School, “which functioned as a working laboratory for developing new methods in the treatment of disturbed children who lived full-time within its walls,” Donvan and Zucker write.

Throughout the 1950s, Bettelheim conducted research and wrote books about autistic children. Autism, as Bettelheim saw it, “was a decision children made in response to the cold, nasty, threatening world in which they found themselves,” according to Donvan and Zucker.

Worse, they add, those who looked at the work of Bettelheim and similar theorists “felt they had learned a brutal but necessary truth: mothers cause their children’s autism.”

Time magazine even did a story in 1948, using the term “refrigerator mothers” to describe the supposedly cold women who were doing a poor job raising children who “never defrost.”

A generation of women ended up blaming themselves for causing their children’s autism.

Donvan says, “A lot of older women would subject themselves to years of psychotherapy to reverse the damage” caused by this ill-informed blame.

“Every respectable psychiatrist believed this – with no evidence. There was no research. The field believed it already had the answer so there was no point doing any research,” Donvan says.

But Irish Catholic mothers such as Ruth Sullivan, who helped found what is today known as the American Autism Society, refused to believe the thrust of Bettelheim’s argument.

“That’s where the drama and – we hope – the inspiration comes in,” says Donvan. “It’s a really amazing story.”

How much has changed about the way we view autism?

Consider a night in 2012 at the Beacon Theatre on Broadway in New York City. Bold-faced names from George Clooney and Tina Fey to Tom Hanks and Chris Rock turned out for a fundraiser, which pulled in not six, not seven, but eight figures. The event, hosted by Jon Stewart, was the Night of Too Many Stars, created by comedy writer Bob Smigel and his wife Michelle, who have a teenaged son named Daniel “with a most challenging form of autism,” Donvan and Zucker write.

They add: “When Daniel was younger, and at the point where the Smigels realized they could never give him the ability to speak – or alter most of the other lasting limitations to his independence – they figured out what they could do.”

And that, ultimately, is what is most memorable about Donvan’s book. It charts not only the changes and challenges that parents of autistic children have faced, but their activism as well.

Once, autism “was shrouded in shame, secrecy and ignorance – certainly not a cause to which movie stars lent their names,” according to Donvan and Zucker.

Now, “because of the efforts made by parents and activists… public attitudes toward people given the autism label have moved in what all would agree is the right direction.”

What, in Donvan’s mind, is the future of autism?

“I think it’s likely that the number of cases diagnosed will continue to increase, but at a slower rate,” he said. “And then it will stop increasing.”

Is there any credence, in Donvan’s opinion, to the theory that some environmental factor is contributing to the rise in autism?

“We don’t have good numbers to compare the past to the present,” said Donvan. This makes it hard to precisely measure if more kids actually have autism, or if we are simply “getting better at finding out who has it.”

Donvan adds: “It’s only about 20 years now that we’ve been talking about autism as a spectrum. And Caren and I are not convinced that’s gonna hold up. Maybe these are not all the same things.”

What we do know is that back in 2012, at The Night of Too Many Stars, pop star Katy Perry was joined onstage by Jodi Piazza, an 11 year-old autistic girl who “practiced the piano relentlessly” and whose exuberance with Perry brought tears to many in the room. This is just one of many such inspiring stories chronicled in Donvan’s book. ♦

Leave a Reply